Prime

Evidence used to convict Dr Kirabo

What you need to know:

- The evidence, however, used to convict the doctor is what the courts of law refer to as circumstantial evidence.

- Circumstantial evidence is relied upon by the courts of law when there is no direct evidence linking the accused person to the offence.

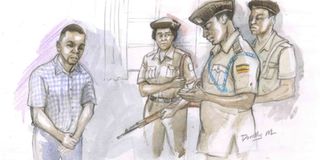

On May 30, 2022, High Court of Uganda sitting at Mukono found Dr Matthew Wabulembo Kirabo guilty of the murder of Desire Jemimah Mirembe and accordingly convicted him.

The evidence, however, used to convict the doctor is what the courts of law refer to as circumstantial evidence.

Circumstantial evidence is relied upon by the courts of law when there is no direct evidence linking the accused person to the offence.

Circumstantial evidence

And in this case the circumstantial evidence was buttressed by the behaviour of the doctor shortly after the death of Mirembe.

Mirembe died when her neck was cut with a very sharp and fairly heavy object and her body dumped in a sugar plantation in Kawoolo, Lugazi some 50km from Kampala.

The actual evidence before court was that Dr Kirabo was with Mirembe a day before her body was discovered.

Dr Kirabo admitted to having assisted Mirembe cut her neck with a surgical blade.

He said this in a police statement, the Charge and Caution Statement that he made. He, however, did not sign this statement as required by law and he later retracted his confession.

Confession under duress

The lawyers for Dr Kirabo contended that the confession was made under duress when the doctor was held in the notorious Nalufenya torture chambers. The law is clear that when a confession is improperly obtained and conflicts with other evidence in the same case, it is unsafe for court to rely on the confession as the sole basis of a conviction.

Courts have also ruled that if there is good reason to think that the chain of events leading up to the confession was started by physical violence (or threat of physical violence) to the person of the prisoner, it would be a valid exercise of a trial judge’s discretion to reject the statement.

Courts of law have also been cautioned to only act on a confession if it is corroborated by independent evidence accepted by court.

Corroboration is not necessary in law and court may act on a confession if it is satisfied after considering all the material points and the surrounding circumstances that the confession cannot but be true.

Voluntary statement

In this particular case court conducted a trial within a trial and concluded that the statement Dr Kirabo made was voluntary, having found no evidence of torture or coercion, a perquisite to making of the confession statement in issue.

The only anomaly that court found was that Dr Kirabo did not countersign the part of the statement where the caution was explained to him.

This, to court, was self-corrected when Dr Kirabo went ahead to countersign his statement on all pages alongside the officer who took down the statement. Court did not find this a fatal omission as the Constitution enjoins court to apply substantial justice without due regard to technicalities.

Confession statement

The confession statement was admitted in evidence alongside the video recording of the reconstruction of the scene of crime. The lawyers representing Dr Kirabo had, however, raised an objection that the video evidence did not conform to the law; that in law a person seeking to introduce a data message or electronic message has a burden of proving its authenticity.

The lawyers submitted that the prosecution did not prove the authenticity of the recording by evidence capable of supporting a finding that video is what it was claimed to be in court.

The police officer who recorded the video apparently told court that he took the recording to his counterparts in police headquarters for processing. The video had unexplained cuts and jumps and contradicting dates on when the video recording was made.

Court, however, ruled that the confession statement was admitted as evidence after a background was given to it and after the video recording was tendered in. Court looked at the law and found that all necessary precautions, as required by law, had been taken and the evidence was rightly tendered in court.

Further, the video was reviewed in court and the witness cross-examined on it and court did not find any discrepancies in the way the evidence was handled. To court the way the evidence was submitted did not violate the Electronic Act as argued by the lawyers.

Video recording

Court heavily relied on the confession made by Dr Kirabo and the video of the crime scene reconstruction to convict him. To court in the video recording Dr Kirabo was clearly seen leading the investigating officers to the scene of crime. There was no iota of force or machination in the recording.

The doctor was seen in jovial mood and voluntarily taking turns to correct police officers in certain aspects of details to which he enthusiastically pointed out.

He was seen at one spot pausing to ask for forgiveness saying he is a born again Christian and regretted the murder of Mirembe. To court, the evidence in the video corroborated the written confession evidence.

One of the points of contention in the trial of Dr Kirabo was that the prosecution did not place the doctor at the scene of crime. The prosecution did not submit independent evidence that Dr Kirabo was in Lugazi the night Mirembe was killed.

It is in law that the prosecution has to place the accused person at the scene of crime.

Such evidence would have included the telephone printouts of Dr Kirabo and Mirembe showing the telephone masts their phones were picking from especially as they travelled from Kampala to Lugazi as purported but police investigations were strangely quiet on this vital evidence.

There was evidence that Dr Kirabo called Mirembe that evening on her mobile phone but that is where the evidence stopped.

Nobody came forward to say that they saw the couple in Lugazi and neither was there any citing of the vehicle near the crime scene.