Telling unspoken stories of sexual violence

What you need to know:

- With the stage and tone set, the writer of these words, a South African poet named Choene Alley Semenya, gets really dark indeed in her poem, “The Road To Recovery”

The finest eloquence is that which gets things done, said former British Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

In similar vein, the Ugandan Poets Against Sexual Harassment, Assault And Rape (UPASHASAR) has deployed the quills of its members to do battle with the ignorance, inertia and sheer criminality born of a conspiracy of silence around sexual violence.

Using the power of poetry as their weapon of choice, UPASHASAR has taken the fight to the enemy.

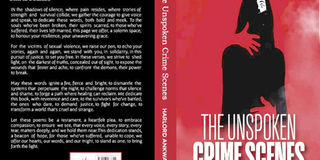

“The Unspoken Crime Scenes is an anthology that dares to confront the most harrowing facets of our existence: sexual assault, lack of justice, the agonizing struggles of survivors, and the prevailing stigma that haunts their very beings. Within these poems, we lay bare the raw emotions and unfiltered expressions of those who have borne the burden of violence, seeking to shed light on the unspoken stories that have been relegated to the periphery of consciousness,” reads the book’s somewhat accusatory Foreword, in part.

With the stage and tone set, the writer of these words, a South African poet named Choene Alley Semenya, gets really dark indeed in her poem, “The Road To Recovery”

“I’m the girl who was violated by a gang of men in the bushes, stripped naked of my dignity, who knows the atrocious feeling of forced penetration, and remembers the sounds of breaking shrivelled leaves on the ground as gravity pulled me down,” Semenya writes.

After being gang-raped, the persona is counseled by her pastor and therapist (a word whose first syllable “the”, which is pronounced “ther”, may be detached from the other two syllables in the word to conjure the ironic words, “the rapist”).

As with other victims of rape, the persona suffers the psychological effects of rape which come with self-blame, self-loathing, feelings of severe anxiety and stress.

Inside, she feels dead and is thus impervious to the exhortations of her pastor to live life anew, since she is not literally dead.

Similar to American poet Sylvia Plath’s persona in her 1962 poem, “Lady Lazarus,” Semenya’s persona is both dead and alive, leaving her at once triumphant, in that she survived rape, and tragic, for the same reason.

Equally disturbing is the poem “My Name Is Nabagesera” by Priscilla Kituuma.

She was a faithful servant of the church from the age of 19; this is when she ripened into a nubile young lady.

Her “chest nuts” doubled as boob eruptions which intruded upon the piety of men of faith.

As a result, Nabagesera, the (in)famous altar girl at the archdiocese, was taken advantage of by those whose care she was entrusted to: the men of the collar or, as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the Kenyan author and academic, would describe as the collared men.

Being an innocent, she surrendered to their sexual overtures, unwittingly thinking that she was serving the church. Until, one day, the road fatefully turned.

“It felt right that I should serve all God’s people/Derived of wives and husbands. It felt an honour to please/A whole seminary single bodily; Until the new priest spoke of harassment, Until a voice spoke of child molestation, Until a voice spoke of the sexual harassment. 40 years of age/My dreams were trapped, My voice silenced…”

Trapped in the vortex of a sex ring, englobing the sexual indiscretions of the church, she is sacrificed at the altar of such perversions and is thereby sainted in sin.

Simon Muhumuza in the poem “I’ll Speak” refuses to go down the same road. The persona in his poem has been defiled, but silence about this crime is not an option. She will speak.

“I am just a minor. Mr. Junju says I can do nothing. I can’t be listened to, Let alone be believed. If I speak, Hell will be my home on earth, Thus he says, I’ll speak! He keeps on pulling me, As if possessed by the devil, Slaps my bums, Fondles my breasts, Forces his disgusting lips, Onto my innocent, juvenile mouth. I’ll speak!”

Although the persona has the courage to speak up against the evils of defilement, she will have to address the suffering from the abuse she endured, which leaves deep emotional scars.

The emotional trauma takes a lifetime to overcome. The persona, a young girl, will tend (thereafter) to look upon sex as a dirty and disgraceful act linked psychically to Mr. Junju, a demon possessed defiler.

If you thought the sins ended there, sorry. The poem “Incest” by Macbeth Mwalim Banda, a Malawian, will pile on the misery that serves as your poetic company.

“I cry day and night/Each night I’m preyed on/Pouncing on me violently Leaving my internals bruised. A demon inside a fatherly deity/Maliciously exposed to torture/Detrimental and a painful one/As Kilimanjaro is placed on Nthawira Hills/So sad! Shamelessly/He says God feeds hard workers/Making me dine after displaying parts private/When I lose my sleep at a minute to midnight/Why me?” Banda writes.

After these words, your heartstrings might as well form a noose that asphyxiates the life out of you. Not because the poetry is so brutally honest, but because the life it reflects is so brutally true.