Prime

44 years later: Why Idi Amin still divides public opinion

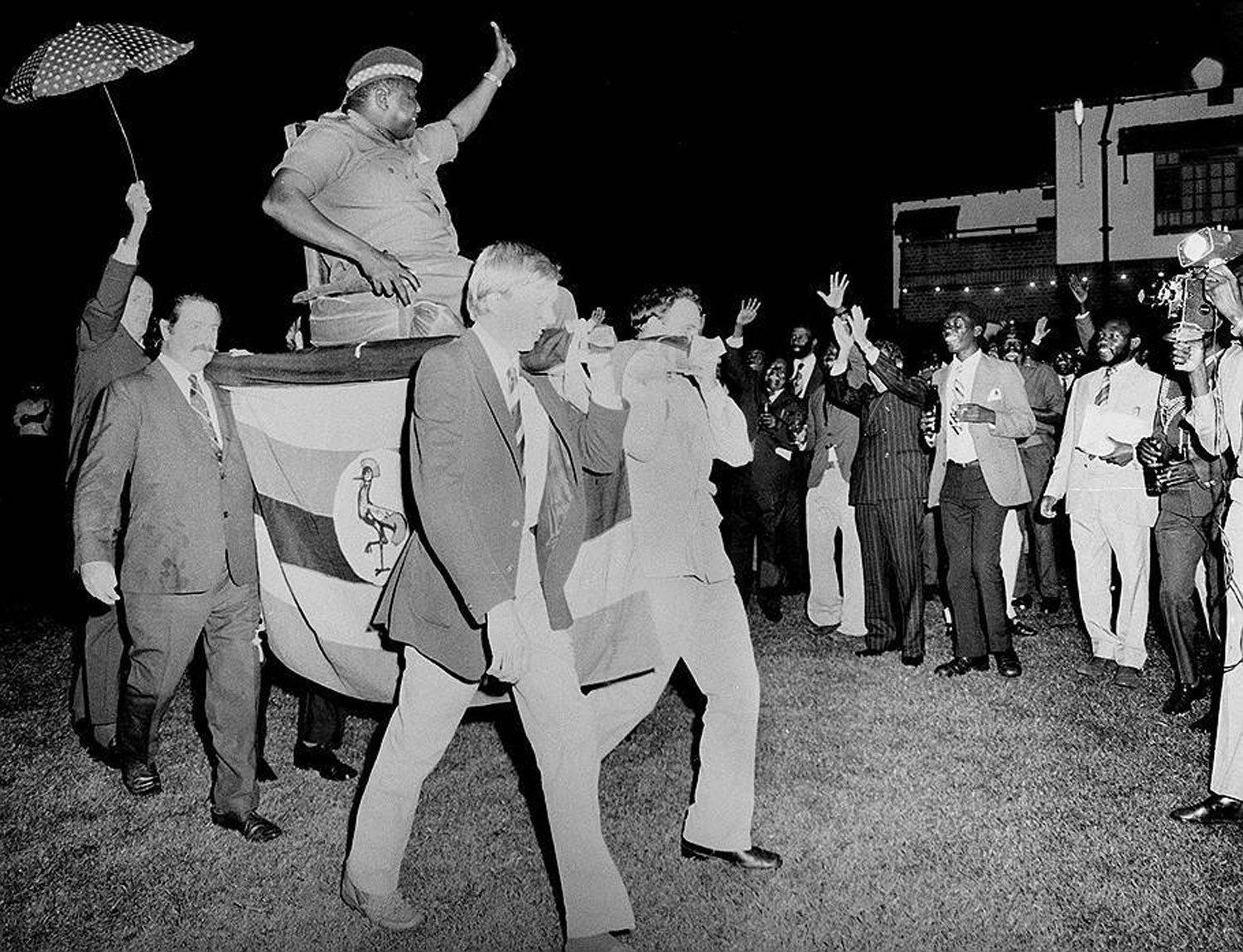

Former Ugandan president Idi Amin is carried by British nationals in the 1970s. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- President Museveni’s insistence that Idi Amin, Uganda’s third president, isn’t worthy to be reminisced has triggered a backlash from Opposition politicians and historians who insist that it’s not possible. Derrick Kiyonga writes that 44 years after he was ousted from power and two decades after his death Amin’s legacy incites varied extreme emotions with the downtrodden not willing to disremember him while to the elites he is the last thing they want to remember.

The downfall of Idi Amin’s eight-year-old administration on April 11, 1979 – after a combination of Tanzanian forces and armed Ugandan groups that were living in exile overpowered his army – was punctuated by lawlessness as exemplified by the eviscerated shops and ransacked government offices in several towns, including Kampala.

In reaction to this, Yoweri Museveni, who was the Defence minister in the Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) government, the political group that had ousted Amin, called on the public to turn in “agents and collaborators of Amin’s regime of death and misery” in what he termed as “the national interest”.

Amin could have died in 2003 in Saudi Arabia, but 44 years after his ouster, Museveni, who has been winning controversial elections and has now ruled Uganda for 37 years, has made it clear that Amin should be forgotten on account of gross human rights violations that were manifested during his rule, unconstitutionality of his regime and mismanaging of Uganda’s economy.

“We do not have to talk about Amin destroying the Ugandan economy by his ignorant expulsion of our Indian entrepreneurs that went away to enrich Canada and the United Kingdom,” Museveni said as he instructed his wife, Janet, who is also minister of Education, to rebuff a request by former Obongi County Member of Parliament Kaps Fungaroo to license an institute in memory of Amin.

“Therefore, it is not acceptable to license an institute to promote or study the work of Amin. It is enough that the forgiving Ugandans forgave the surviving colleagues of Idi Amin. Let that history be forgotten.”

Although Museveni doesn’t want Amin to be remembered, the opposite is happening in downtown Kampala where it’s commonplace to find bod boda (motorcycles) and taxis sporting stickers of Amin, displayed along with those of former South African president Nelson Mandela, former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi and Osama bin Laden, who founded the terrorist organisation al-Qaeda.

In a book titled Nasser Road: Political Posters in Uganda, Kristof Titeca says Amin’s appeal was the theatrical manner with which he resisted imperial powers and sometimes humorous, sometimes cynical, sometimes over top, and often all of these together, further amplifying the power and appeal of messages.

“Sometimes people mistake the way I talk for what I’m thinking. I have never had any formal education – not even nursery school certificate. But, sometimes I know more than PhDs because as a military man I know how to act, I’m a man of action,” Amin was quoted in Thomas and Margret Melady’s Idi Amin Dada: Hitler, Kansas City, 1977.

In his paper titled, Between Development and Decay; Anarchy, Tyranny and Progress Under Amin, Prof Ali Mazrui, who passed on in 2014, wrote that Amin converted the whole world into a stage, trying to force some old imperial myths through the exit door, and to bring in new defiant myths of Black assertiveness.

Amin, per Mazrui, endeared himself to nationalists by publicising a number of pictures that were staged managed in order to make fun of the West and the history of colonialism.

In one picture that still trends to date, Amin is carried in a loft and kinglike in a sedan chair by four British officials.

In another picture that also gained fame, about 14 Caucasians are seen kneeling in front of Amin, pledging allegiance to the “conqueror of the British Empire” and consequently being sworn in Amin’s army.

“These actions,” Mazrui contended, “were means by which Amin further strengthened his anti-imperial stance. A deliberate comedy was unfolded upon the world stage, poking fun at the world and its ways.”

In rejecting Amin’s memorial school, Museveni claimed said Amin’s government was “clearly illegal”.

President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni. PHOTO/FILE

“Why?” Museveni asked.

Though Amin overthrew Apollo Milton Obote in 1971 via a military coup, Museveni seemed to blame him for the abrogation of the post–independence constitution in 1967.

“The Constitution was altered in 1966/67 by Parliament and had been elected in 1962. Were their actions constitutional?” Museveni asked, adding that it needed to be debated but he insisted Amin was clearly unconstitutional.

Perhaps what Museveni meant is what Prof George Kanyeihamba detailed in his book Evolution of Constitutional Law, Public Law and Government saying Amin ruled through constitutional decrees and used the army as the main instrument of government.

On taking power, Kanyeihamba writes, Amin endeared himself to the Baganda when he greenlighted the return of the remains by Kabaka Edward Muteesa and also ordered the release of all political prisoners.

Beyond that, Kanyeihamba says Amin vested in himself powers to make laws and anyone who violated them was heavily punished.

Laws, Kanyeihamba says, like detention decrees were put in place ostensibly to limit political activity in the country.

“During this period, judicial independence was undermined because Amin introduced quasi-judicial tribunals headed by atrocious and despotic officers such as ‘commander suicide’,” Kanyeihamba says.

Although Museveni branded Amin’s regime as “unconstitutional” many were quick to remind him he wasn’t any different because he used the gun to take power in 1986 after he lost the 1980 general election.

“Just like Amin, Museveni came here by use of a gun to a great extent it [a gun] has helped him maintain power. I wonder where he gets the moral authority to say that Amin’s regime was unconstitutional yet they did more or less the same thing,” says Mwambutsya Ndebesa, a political historian at Makerere University’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

Just like Amin, Museveni for a great part of his rule had abolished political parties.

“The foundation of Uganda’s ‘no-party democracy’ is the principle of what is called ‘individual-merit politics. The latter was articulated by the NRM leadership as a reaction to a post-independence history of sectarian and ethnically based political parties, the alleged cause of sequential patterns of ethnic exclusion, political violence and chronic instability,” Giovanni Carbone writes in his paper ‘Hegemony and Opposition Under Movement Democracy’ in Uganda.

“Thus, parties were ‘banned’ (or, in fact, marginalised) and all Ugandans were declared members of an overarching Movement. While party activities became subject to strict limitations prohibiting delegates’ conferences, public rallies, local branches, and the sponsoring of candidates for election,” he adds.

Museveni also said Amin doesn’t deserve to be remembered on the account of destroying Uganda’s economy through measures such as expelling of Indians, something the President said, went a long way in enriching countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom where the Indians settled.

What Museveni was relating to was the 1972 agenda that Amin dubbed the “War of Economic Independence”, or “Economic War” in which Amin summarily decreed the expulsion of Uganda’s Asians.

More than 50,000 Asians, researcher Derek Peterson says, were given a limited three months to gather their belongings and leave the East African country.

Former Ugandan president Idi Amin makes British nationals kneel before him in 1975. PHOTO/FILE

Claiming that he was expelling Asians as a result of a dream he had got from God, Amin accused them of “sabotaging Uganda’s economy, deliberately retarding economic progress, fostering widespread corruption and treacherously refraining from integrating in the Ugandan way of life”.

The result was that 5,655 farms, ranches and estates had to be vacated by the departing Asian community. The uninhabited properties fell under the custodianship of a new bureaucracy – the Departed Asians Property Custodial Board – which distributed houses and business premises to African tenants.

The Asians who went to the United Kingdom, The Economist reported in 2022, shone. It is estimated, The Economist reported, that the Asians might have created 30,000 new jobs in Leicester, a city found in the midlands of England, alone.

“One recent academic study found that within 40 years of their arrival, they were ‘significantly over-represented among professional and managerial occupations’,” The Economist wrote.

The expulsion of Asians inevitably impaired Uganda’s already limping economy. The gross domestic product (GDP) fell by 5 percent between 1972 and 1975, while manufacturing output tumbled from Shs740 million in 1972 to Shs254 million in 1979.

The economic statistical data at the time favoured Amin’s argument as it showed that the Indian community exploited the economic set-up and African agricultural producers both ways – as exporters of semi-processed raw materials extracted from near-slave labour and also as majority sellers of manufactured goods to the rest of the country at exorbitant prices.

Prof Samwiri Lwanga Lunyiigo in his book Uganda an Indian Colony 1897-1972 describes Amin as a raw peasant soldier, unschooled in basics of statecraft, but he had noted the extremes of wealth and poverty in Uganda hand decided to do something about it.

Indians, according to Lunyiigo, held most of Uganda’s wealth and the indigenous Ugandans who were around 99 percent of the population largely lived in excruciating poverty.

To Amin, Lunyiigo says, the only way he could do something was to get rid of Indians, citizens, and non-citizens alike.

“His dream was to create native millionaires and he couldn’t do this if Indians did not leave. In this process he was working inadvertently towards sovereignty, a sovereignty which got stuck in poverty and misery but sovereignty nevertheless,” Lunyiigo says.

Though Lunyiigo admits that Amin’s economic stewardship was chaotic, he admits that expulsion of Asians was therapeutic to most natives.

“It healed many wounds of the native souls,” Lunyiigo says. “They experienced some restoration of lost dignity as human beings after humiliation of the Indian presence in their villages and their ordained role as hewers of wood for Indians,” Lunyiigo says.

One of the key accusations against Amin that Museveni repeated was human rights violations and mass murder. Museveni insisted that Amin, or his henchmen, killed Uganda’s first Black Chief Justice Benedicto Kiwanuka, Obote’s Internal Affairs minister Basil Bataringaya, Anglican Archbishop Janani Luwum, Lango and Acholi soldiers, among others.

Indeed, many books claim that Amin’s reign was characterised by killings, torture, and abductions with more than 80,000 people killed.

“Amin’s informers were to be found everywhere as their license to kill, maim, detain or extort was not subject to any restraint,” historian Sawmiri Karugire wrote in his book A Political History of Uganda.

Despite the apparent human rights violations, some of which have been denied, Amin has remained in the good books of many Ugandans and Africans at large.

“He had that profound dialectical quality of heroic evil. And whether one applauded the heroism or lamented or denounced the evil depended upon one’s priorities,” Prof Mazrui wrote.

“In other words, Amin significance in the 1970s was more positive in international affairs than in domestic affairs. The degree to which the third world was ready to forgive his domestic excesses provided he remained in resistance to the mighty, was indicative to a major moral cleavage between the Northern hemisphere of the affluent and the Southern hemisphere of the exploited and underprivileged.”

View

Expelling Asians.

His dream was to create native millionaires and he couldn’t do this if Indians did not leave. In this process he was working inadver-tently towards sovereignty, a sovereignty which got stuck in poverty and misery but sovereignty neverth-eless,’’ Prof Samwiri Lwanga Lunyiigo in his book Uganda an Indian Colony 1897-1972

President Museveni’s views on Amin: Idi Amin’s government was clearly illegal. It had no right to install itself over our country.

Apart from his unconstitutionality, he committed a lot of crimes—the killing of the Acholi and Lango soldiers in Mbarara, the killing of the prisoners in Muukula prison, and the killing of Ben Kiwanuka, Basil Bataringaya and his wife and so many other killings.