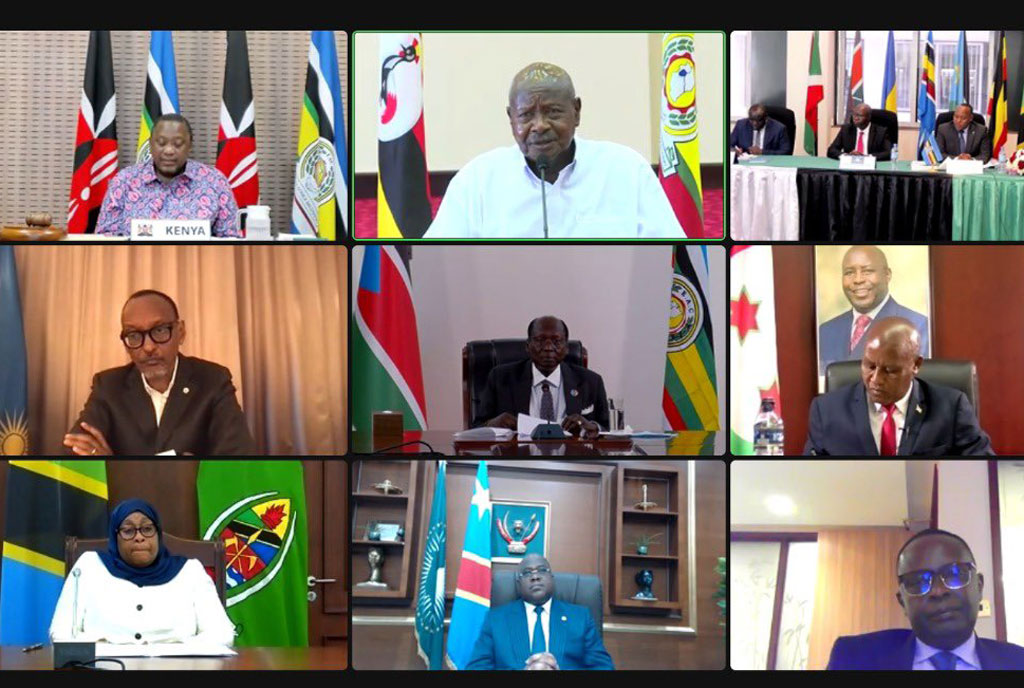

Rwandan President Paul Kagame (left) and DR Congo President Felix Tshisekedi(right) arrive in Nairobi, Kenya, for the signing of the treaty of accession that made DR Congo the 7th member of EAST African Community (EAC) on April 8, 2022. PHOTO/ RWANDA PRESIDENCY

|People & Power

Prime

Rwanda-DR Congo row: Tensions rise again in the Great Lakes

What you need to know:

- When DR Congo was admitted to the East African Community three months ago, I wrote an analysis in Sunday Monitor in which I expressed skepticism over that and promised a future analysis, which has arrived.

Tensions erupted last week between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda.

Demonstrations were held this week in the Congolese capital Kinshasa to protest Rwanda’s support, or suspected support, of the M23 rebels. The protesters mentioned killings by the M23.

Across social media, there was much anger being expressed by Congolese over what they said was Rwanda’s abuses on Congo’s territory for more than 25 years now, many denouncing what they regard as Rwanda’s efforts to balkanise Congo.

Wrote one Congolese on the social media platform Twitter on May 31: “Kagame knows that an open war with the Congo is certain death for him. Don’t listen to people who tell you that the Congo can’t do anything. Congo will demolish Rwanda in record time.” (translated from French.)

With Ugandan troops in Congo, the tensions are bound to deepen not just between Congo and Rwanda, but between Rwanda and Uganda, as will later be explained.

When the Democratic Republic of Congo was admitted to the East African Community three months ago, I wrote an analysis in Sunday Monitor in which I expressed scepticism over that.

Noted my April 3, Sunday Monitor article: “Somewhat suspiciously, on March 27, the day before DR Congo was scheduled to be admitted to the EAC, the Tutsi-led Congolese militia, M23, decided to launch an attack in Congo’s eastern region of North Kivu. The consequences of that M23 attack almost certainly will be the subject of a future Sunday Monitor analysis.”

The consequences of that M23 attack and the future Sunday Monitor analysis have arrived, as anticipated two months ago.

The tensions between Congo and Rwanda that took a serious turn last week bore out my doubts about the wisdom of an expanded East African Community.

It was obvious to anyone familiar with the Great Lakes region of eastern and central Africa that M23’s recent resurgence would be the source of new security tensions.

There is just too much political and ethnic baggage in the Great Lakes region for its new members to contribute meaningfully to economic integration with the original states of Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.

M23 has been a thorn in the side of Congolese-Rwandan relations since it emerged in 2003 at the tail end of the second great Congolese civil war that drew in neighbours such as Uganda, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Angola.

The rebel group is widely viewed as a proxy created or supported by Rwanda to protect Rwanda’s security interests in eastern Congo and it has been accused of carrying out many atrocities against civilians inside Congo.

All this comes on the back of the four-year tensions between Rwanda and Uganda during which Rwanda closed its border to Uganda.

In this period, Uganda turned more and more to strengthening its relations with Congo, partly to offset the loss in trade with Rwanda and partly to find a road route around Rwanda should relations remain bad between Kampala and Kigali.

Uganda embarked on building a major new road leading into eastern Congo from Uganda’s Rwenzori area. Congo invited Uganda into its eastern North Kivu region in pursuit of the Ugandan ADF rebel group.

A business summit took place in Kinshasa this week between Congo and Uganda.

North Kivu is Rwanda’s main sphere of influence in Congo and this Ugandan deployment in North Kivu is a matter of concern to Rwanda.

In early February, President Museveni dispatched his son, Lt Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba, to Kigali for talks with Rwandan President Paul Kagame.

Uganda’s pledge

Uganda pledged to distance itself from the Rwanda National Congress (RNC), the opposition group that Kigali says wants to overthrow Rwanda’s RPF government.

This led to the re-opening of the Rwanda-Uganda border.

The new situation in Congo, however, overtakes the thaw in relations over Ugandan alleged support for the RNC because of several reasons.

Ever since RPF came to power in Kigali in 1994, it has emerged as a regional power but has also lived with a constant sense of insecurity.

The RPF government is conscious of Rwanda’s small size and location in a region where it is surrounded by large neighbours like Tanzania, Congo and Angola, and smaller but potentially hostile neighbours like Burundi and Uganda.

The RPF’s foreign and security policy since 1994 has largely been, at its core, that any country or any government that supports or offers shelter to enemies of Rwanda is to be taken as hostile to Rwanda, i.e., my enemy’s friend is my enemy.

This policy is what increased tensions between Rwanda and Uganda over the RNC.

It is what has made Rwanda maintain a foothold in eastern Congo since 1994 after remnants of the former Rwandan government of president Juvenal Habyarimana took up positions in Congo.

For as long as elements of Rwanda’s former army remain in Congo, there will always be tensions between Kigali and Kinshasa.

And for as long as relations between Congo and Uganda keep improving, relations between Rwanda and Uganda will have the potential to suddenly take a turn for the worse.

Since closer ties between Congo and Uganda are coming during these heightened tensions between Congo and Rwanda, Kigali is likely to view this as an indirect sign that between the two, Uganda sides with Congo over Rwanda. In other words, the easing of relations between Rwanda and Uganda in the wake of Gen Muhoozi’s trip to Kigali in February has been overtaken by the rising tensions between Congo and Rwanda.

For this reason, any military deployment in Congo by Rwanda and Uganda could eventually lead to these two countries turning on each other.

Remember, Uganda’s current troop deployment in Congo is not far from North Kivu, Rwanda’s area of control.

Given its size of population and its well-known wealth of minerals, Congo is potentially one of Africa’s richest countries, if not the world.

For this reason, Congo is on paper much more strategically and economically more important to Uganda than Rwanda. In spite of the historical 40-year relationship between the current leadership in Rwanda and Uganda.

Uganda is currently trying to shift its relations with Congo from a preoccupation with civil war and refugees to one focused on mutual economic interests.

The three-year closure of Rwanda’s border with Uganda taught Uganda’s NRM government never again to place its regional economic interests at the mercy of the mood in Kigali, so increased economic engagement with Congo is Uganda’s Plan B.

Therefore, the easing of tensions between Rwanda and Uganda that led to the re-opening of the border in February could see a reversal.

The original East African Community that came into being in 1967 and comprising Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda was focused on economic relations.

The eastern half of the East African Community (Kenya, Tanzania) is mainly interested in trade and cross-border movement of people; the western half (Congo, Rwanda) is primarily concerned with internal security, refugee crises, and the operations of armed rebel groups.

Uganda is somewhere in the middle: Part of it is preoccupied with the security interests of the western half of the East African Community, and part of it is concerned with the economic interests of the eastern half of the Community.

The East African Community’s enlargement from the original core with Kenya at its heart to an EAC with half its members still bogged down in ethnic wars and tensions, means that it is being forced to carry the baggage of these members from the unstable Great Lakes region.

This, then, is the price that will be paid for enlarging the East African Community with commercial ties foremost in mind and without having taken into account underlying political relations.