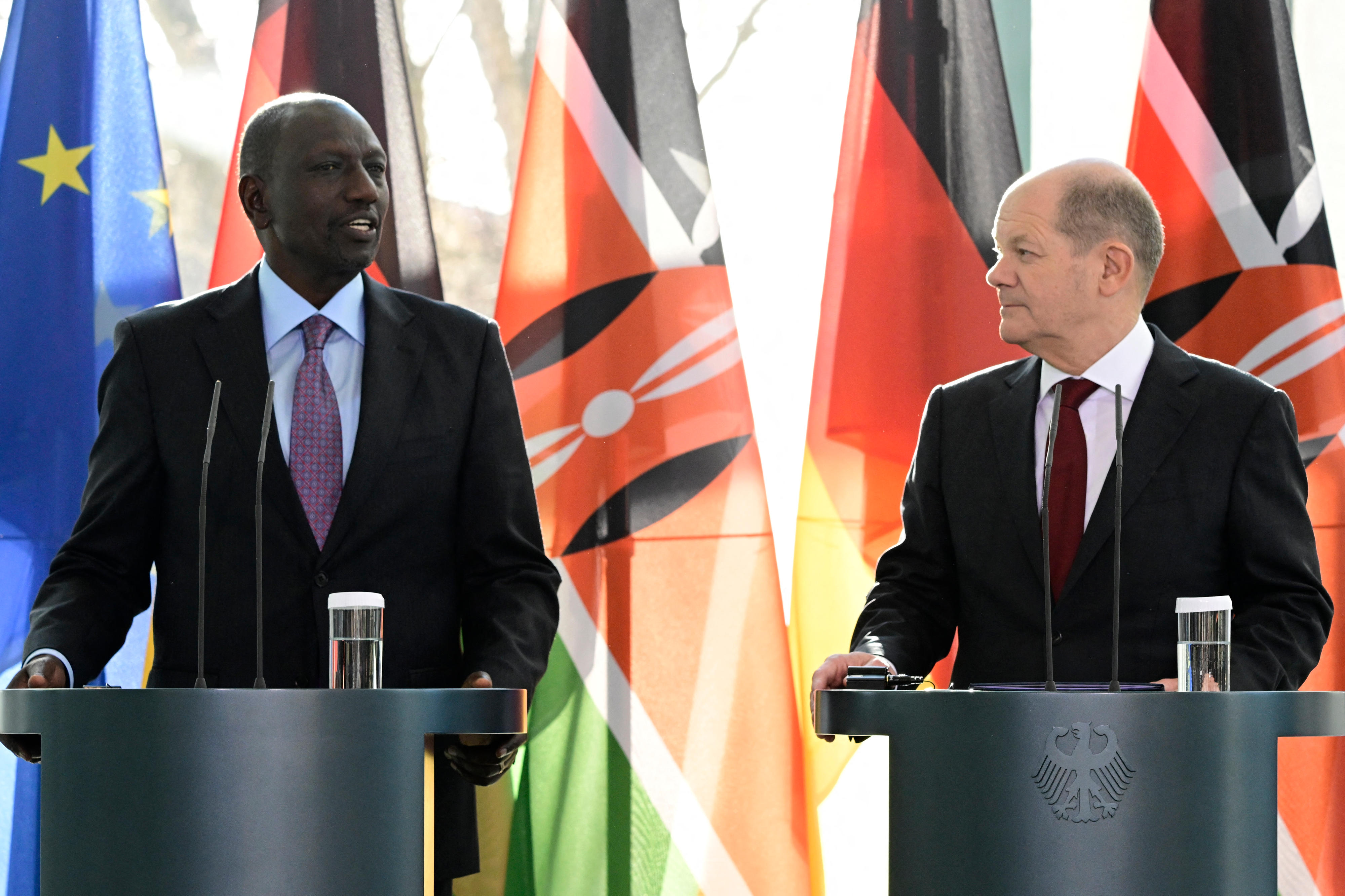

Prime

The roots of Kenyan politics

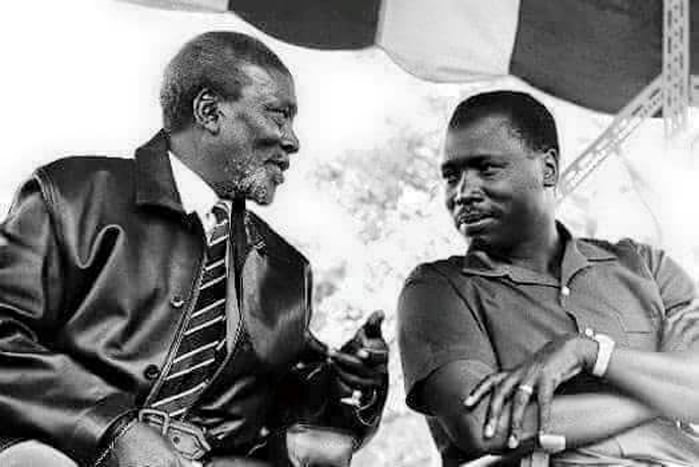

Founding Kenyan president Jomo Kenyatta (left) and his then vice president Daniel arap Moi. Photos/FILE

What you need to know:

- Unlike most of Africa that the British regarded as overseas territories to be governed indirectly, Kenya was designated as a White settler country. Thus, Kenya inherited Britain’s class system.

The December 2007 general election in Kenya marked a turning point in the country’s history.

Because of the two-month violence that followed, Kenya went from being perceived and perceiving itself as an oasis of stability in a region of instability, to the country and the world at large holding their breath every time Kenya goes to the polls.

When this violence did not occur after the August 2022 general election, with relief many started to feel that 2007 was a tragic exception and Kenya was back on its decades-old stable feet.

When anarchy broke out last week, including an arson and looting raid on a farm in Ruiru owned by the family of former President Uhuru Kenyatta, nervousness returned.

Despite the relatively calm polling day and its aftermath last year, this analyst posted a note on his social media platform Twitter on August 9, 2022: “We are now in the danger zone. There is going to be post-election violence; the only question is the degree. At worst, 2007/2008; at best, simmering anger among a large section of the Kenyan population that will simply refuse to recognise the new president.”

It turns out that the only difference between December 2007 and August 2022 is that the violence erupted immediately in 2007 while it was pent-up in 2022 and erupted seven months later.

Why was the latest eruption of anarchy and looting inevitable?

There are many factors but the core one is rooted in Kenya’s physical geography. The physical geography shapes the economy, which in turn underpins the politics.

Although Kenya is well-known as an agricultural country, the largest producer of tea in Africa and one of Africa’s largest producers of coffee and flowers, it is actually a largely barren country.

Most of Kenya’s population is concentrated in the south-central highlands and the Great Rift Valley in the central region, the western region up to the border with Uganda, south to the Tanzanian border, and a 20-kilometre strip in Mombasa along the Indian Ocean.

The country is greenest in the central highlands around Mt Kenya and surrounding towns and districts Embu, Meru, Nairobi, Nyeri, Murang’a, Thika, then Nakuru, Kakamega, Kericho, Kitale, Eldoret, Bungoma, Kisumu, Busia, and the coastal strip from Mombasa and north to Malindi, Kilifi, and Lamu.

The rest of the country is semi-desert.

“Kenya’s geography (80 percent semi-arid) leads to a high population density in the fertile areas, which creates a dog-eat-dog society, and so shapes politics,” I commented on Twitter on August 10, 2022.

Kenya is the seventh most-populous country in Africa, one place behind South Africa and one place ahead of Uganda.

Uganda, unlike Kenya, is about 80 percent fertile and at most only about 10 percent semi-arid.

So, Kenya’s population of 56 million must struggle to survive on the 20 percent fertile land.

Due to reasons rooted in the White settler colonial period and carried on after independence in 1963, most of that 20 percent fertile land is either devoted to large-scale commercial agriculture or owned by a few wealthy political families.

In other words, while much of this fertile 20 percent is under agriculture, the crops in question are coffee, tea, pyrethrum, sugar, and flowers: non-food agricultural crops.

A smaller fraction is under food crop cultivation.

One can literally starve to death in Kenya if one does not work (or if, unemployed, one does not steal.)

This explains why Kenyans tend to be aggressive go-getters when compared with their neighbours.

Tanzanians, Rwandans, Ethiopians and Ugandans tend to find Kenyans quite rough, unsentimental and even a little uncouth. Well, now we know why.

It is the reason why the price of Kenya’s staple food posho (or unga, as it’s called in Swahili) is such a sensitive political matter in a way that might puzzle a typical Ugandan for whom the price of food has never, even during the worst political eras, been a political issue.

Because of the reasons of land scarcity, digital networks like the Internet and mobile phones when they arrived, were more intensively embraced by Kenyans than most other Africans.

Former president Uhuru Kenyatta.

At last, here was territory (the Internet, social media, mobile money) that was free of the constraints of geography and land.

Kenya has more Facebook users than Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda, South Sudan and Rwanda combined and Kenya has the highest Internet penetration of any African country (89.4 percent), followed by Morocco, Mauritius and South Africa, in that order.

It explains why services are more developed and more competitive in Kenya than in the rest of East Africa and in most of Africa. Not only is Kenya Africa’s seventh most-populous country, but it is also Africa’s seventh-largest economy.

Uganda, for its part, is Africa’s eighth most-populous country but 14th-largest economy, meaning that Uganda is an underperforming economy or its population is under-productive when compared with Kenya’s.

This pressure on the little fertile land and the very real prospect of a person starving to death, also explains the notoriety gained by the capital Nairobi for crime, causing Kenyans in the 1990s to nickname the city “Nairobbery”.

One could ask: Isn’t Kenya’s northern neighbour Ethiopia’s physical geography much like Kenya’s? Why is it Kenya that is prone to post-election violence and high crime rates?

Only 13 percent of Ethiopia’s land is arable, that is, conducive to agriculture, while 87 percent is arid, semi-arid, or mountainous.

Because Ethiopia was under hard-line military and Marxist rule from 1974 to 1991 and Socialist and semi-Capitalism since 1991, its political culture resembles more Tanzania’s than Kenya’s.

However, this pressure on the 13 percent arable land in Ethiopia tends to produce its own political violence which, while not armed robbery and post-election clashes like Kenya, manifests itself in what seems like decades of endless armed ethnic groups and factional fighting, the latest of these eruptions being by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in November 2020.

The physical geography of Kenya and the ownership of the little fertile land furthermore explains why there is such a sense of bitterness, consciousness of social injustice and economic struggle in the society.

On top of all this, Kenya from the colonial era was capitalist to the present day, with Capitalism’s competitive tendencies.

Unlike most of Africa that the British regarded as overseas territories to be governed indirectly, Kenya – along with South Africa, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and Algeria for the French – was designated as a White settler country the way Australia and New Zealand are.

Thus, Kenya inherited Britain’s class system. This class stratification can be seen and felt everywhere in Kenya, in its pretentious white-collar middle class that unabashedly apes all things British and American.

There is great emphasis, in Nairobi especially, on one being defined by the schools one attended, which neighbourhood one lives in, where one shops, what car one drives, and what private members’ club one belongs to.

Little wonder that there are secondary schools in Kenya with fees in the tens of thousands of dollars, in an imitation of the British public schools Eton, Harrow, and others, and such sports as Polo.

The reaction to this class stratification in Kenya is seen in the popularity of the music genre Reggae, historically the music of the downtrodden of its birthplace Jamaica and later, the music of the urban dispossessed in sub-Saharan Africa.

Reggae’s main themes are social injustice, European colonialism and enslavement of the African, and the hope of redemption one day from this “Babylon system”.

Another thing is that the Kenyan media tends to focus on leading political figures, with large front-page portrait photos of Daniel arap Moi, Raila Odinga, Mwai Kibaki, Uhuru Kenyatta, William Ruto, Kalonzo Musyoka, or whoever happens to be topical that week.

This emphasis on prominent political leaders also follows a logic. Every president and government is limited by these harsh geographical facts and no matter how sincere they are, can’t change the 20 percent arid, 80 percent semi-desert reality.

The only card they have to play with is the tribal, meaning it is easier to co-opt or win the public’s support not by creating jobs or increasing the acreage under food cultivation, but indirectly by appointing to one’s cabinet prominent figures from various tribes or entering a political alliance with them.

It’s easier for Uhuru Kenyatta to tap into the large Kalenjin population in the Rift Valley by having as his running mate William Ruto than it is to create factory or government jobs in the Rift Valley.

Similarly, it’s easier for Raila Odinga, a Luo, to name Martha Karua a Kikuyu as his election running mate than for him to create concrete policies that address the problem of land scarcity in the Kikuyu areas around Mt Kenya.

By focusing on symbolic, token representation at the seat of power rather than addressing individual voters’ problems, tribal politics has become entrenched in Kenya.

When all these factors and forces are taken together, one gets a clear picture of why Kenya is the way it is, most of it rooted in its geography.