Prime

Uganda and Rwanda’s feudal rule

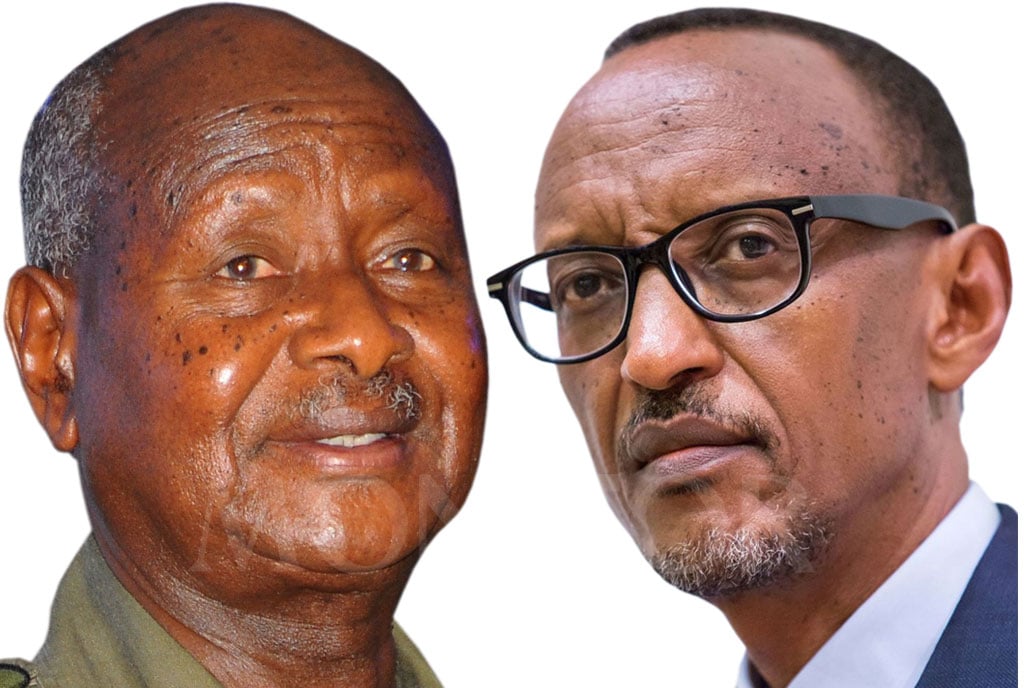

Presidents Museveni and his Rwandan counterpart Paul Kagame . Photo/ File

What you need to know:

- It’s also the story of the two similar systems of government: How they achieved relative stability by recreating 19th Century feudalism, with power moved from state institutions to the royal court.Much of the instability experienced by Africa starting in the 1960s with the dawn of self-rule was that these states were founded on the modern European model of impersonal and independent institutions.

Last week, Ugandan social media was up in arms over the revelation that General Salem Saleh, brother of President Yoweri Museveni, is directly involved in the making of decisions over what use to put NSSF funds.

Ugandans have by now become accustomed to the personalisation of state power by Museveni and his family.

But this still came as a shock to many. Even the usually apolitical and indifferent white-collar corporate types spoke out.

This week, I examine the two NRA governments, the one in Kampala and its Kigali offshoot.

Last week, after all, photos were published of Lt. Ian Kagame, son of President Paul Kagame, fresh from cadet training in Europe, and newly deployed in the presidential guard.

To Ugandans, this is familiar and most won’t have difficulty seeing where it will eventually lead.

It’s intriguing how closely RPF Rwanda tends to mirror the NRM Uganda from which it was an outgrowth.

It’s also the story of the two similar systems of government:How they achieved relative stability by recreating 19th Century feudalism, with power moved from state institutions to the royal court.

Much of the instability experienced by Africa starting in the 1960s with the dawn of self-rule was that these states were founded on the modern European model of impersonal and independent institutions.

European-style democracy and civil service did not seem to work in Africa. Nobody had a strong personal connection to and feeling of ownership of the state.

Recently having emerged victorious from guerrilla warfare, the NRA and eight years later the RPF, working more by raw, gut feeling and the habit of ingrained culture, arrived at a method by which all power was centred in the hands of the president

It was his to decide what to do with it and whom to appoint to carry out his orders. Loyalty to the president became the quality that mattered above all.

It soon because clear, unofficially, that to get anything done or secure one’s way, one had to talk to Gen Saleh to talk to President Museveni

Or to talk to Gen Kainerugaba to have him talk to his father, or to talk to a hypothetical Barbara Aainemebabazi to put in a word for one to the First Lady Janet Museveni.

This is how we arrived at the point where decisions concerning something as important as the national pension fund are made at the home of Gen Saleh.

In Uganda and Rwanda, one might have a government or hold any other public office, but everyone is aware how powerless these offices are, with State House being the seat of government in every way.

State House Uganda is a government within a government, with a desk or department that handles virtually every role the line government ministries are supposed to be.

As Uganda’s economy runs out of growth, with consumer demand no longer able to sustain businesses, society returns fully to feudalism’s modularity.

A few political leaders control the money bags and so everyone finds ways to praise these leaders in order to get cash and job handouts.

Over the past year, the four most visible centres of state patronage have been President Museveni, Gen Saleh, Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, and lately the Speaker of Parliament Anita Among.

Ugandans who in the late 1980s and 1990s thought getting a university degree or advanced MBA would be the key that opens career doors now discover that MBAs are not what the Museveni government is looks for.

What it really looks for and expects is loyalty to and subordination to the House of Kaine, the First Family.

To make any career or financial progress in Uganda, it’s not competent management, high education, or hard work that are required.

You must constantly watch the political mood and, above all, align yourself with the First Family’s objectives or, at least, not step out of line of those objectives.

Then you will do well.

Across the border in Rwanda, the appearance of order and efficiency aside, it is the same state of affairs as Uganda.

All journeys might begin in the body politic and economic middle class in terms of business startups and creative ideas, but they can only go so far before they need to end up at State House on the desk of President Kagame.

It is then up to him to decide what should be done. If your project or proposal makes sense to him, all doors will open in funding and government backing.

When you fall out with President Kagame, the floor opens up under your feet.

You get ostracised by society itself, not because you’ve necessarily committed a crime or that President Kagame will order your arrest.

In this neo-feudalism where personal relationships are the basis oil public life in Rwanda, just to be perceived as having lost the favour of the head of state makes you a liability to your friends, business associates and neighbours.

Nobody knows why they start to avoid you; they just start doing so out of some vague, undefined fear.

This explains, in part, the atmosphere in Kigali that almost everyone local resident or foreigner is acutely aware of.

The reason traffic rules are generally respected and plastic bottles are not thrown out of car windows as is typical in Uganda, is not because Rwandan society has a deep-down philosophical understanding of the need to maintain clean and orderly towns.

It is because everyone is afraid of the powerful and disciplinarian individual called Paul Kagame.

To get by, one has to be guarded about one’s views, careful about whom one confides in, often even unsure if one’s own husband or wife can be trusted.

You either praise the president or you keep quiet.

There is no third way and Rwanda under the RPF has learnt to be a tight-lipped, no-questions-asked society.

Some of this, of course, stems from the tragic events of 1994.

Today’s Rwanda cannot afford to be torn by conflict of any kind. Even the appearance or hint of conflict becomes an existential national crisis.

And yet a certain amount of conflict, like conflict of ideas, approaches to urban development and economic policy, is not only healthy but essential to a country.

Constant exchanges of views, debate, and disagreement heal and strengthen society and help refine perspectives and public policies.

However, Rwanda can’t risk that and so we see this air of calm, dutiful, law-abiding routine in the country, but something doesn’t feel right.

What the Ugandan media in 1994 termed the ‘Hima-Tutsi empire’ was the result of these military victories, and an unintended but inevitable consequence is the current deep mutual mistrust between the NRA and RPF regimes.

On the face of it, the Bahima and Tutsi are nearly one and the same; in reality, there are undercurrents of tension, much like what we saw of the Acholi and Lango in the mid-1980s.

To most outsiders, the Lango and Acholi are the same ethnic group; amongst themselves, though, it rivalry that goes back at least 100 years.

In fact, when Idi Amin seized power in the January 25, 1971 coup, the Acholi at first stood by aloof, seeing it as none of their business and, in fact, secretly pleased to see the Lango president Milton Obote overthrown.

The tensions in the national army, the UNLA, in the early 1980s between the Acholi and Lango that culminated in the July 1985 coup would not have surprised both groups.

Likewise, the on-and-off-and-on tensions between Kampala and Kigali under Museveni and Kagame surprise only those who don’t know of this undercurrent of tensions that were raw even at the start of the NRA guerrilla war in the early 1980s.