Prime

Court assesses evidence in botched surgery

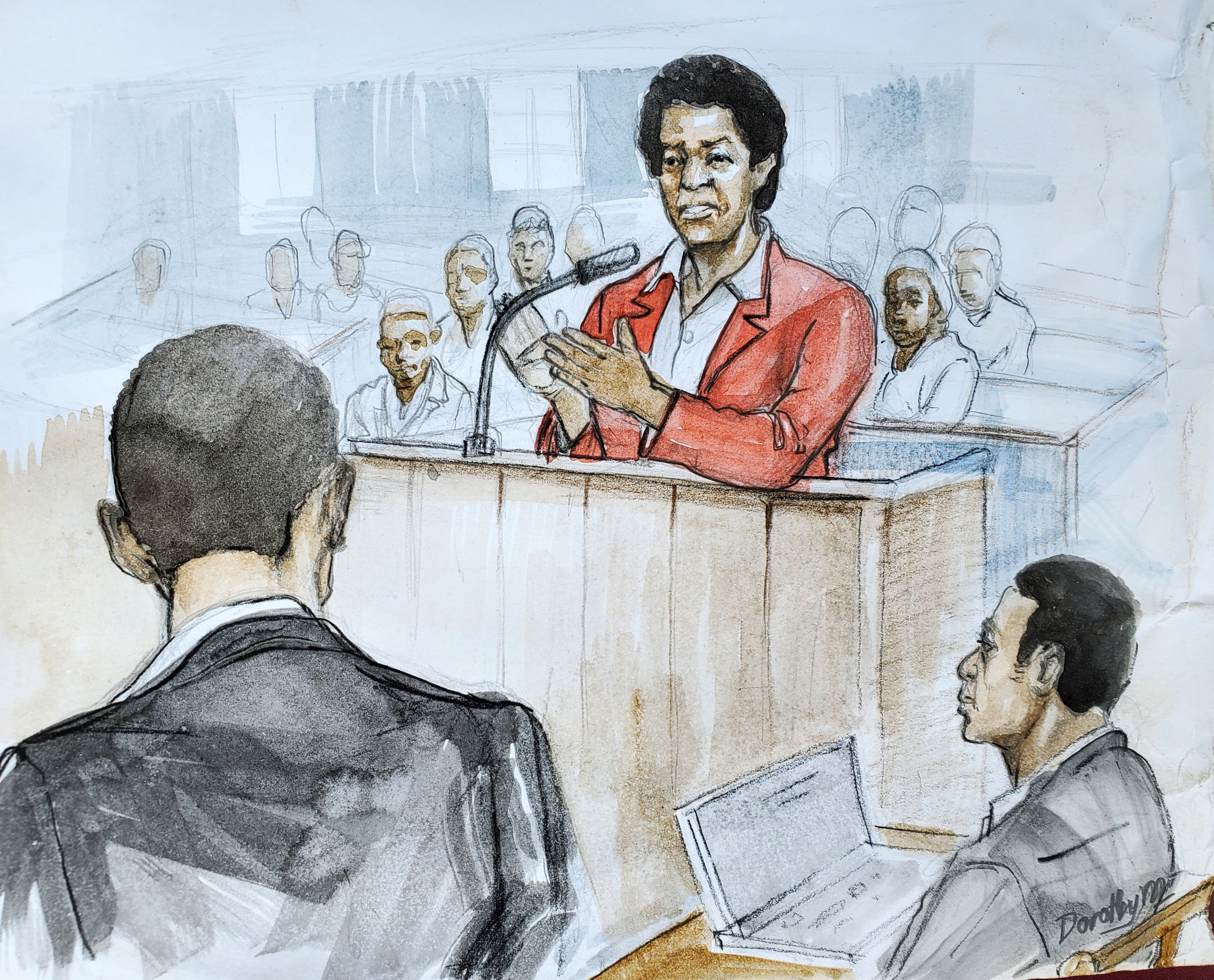

PHOTO: Illustration.

What you need to know:

- Court relied on the legal principle.

A total of five witnesses, including the complainant, testified in a case in which a schoolteacher sued the Attorney General for medical negligence when she developed a fistula after a botched medical operation to remove her uterus.

She had been diagnosed with uterine fibroids and surgery was the best treatment option proposed to her, to which she consented.

Three other witnesses, including two experts, gave evidence in support of the teacher while another expert, a gynecologist, employed in a teaching hospital, gave evidence in support of the Attorney General.

To court there were common facts in the evidence of the five witnesses. It was not in doubt that the schoolteacher was admitted in a government hospital for total abdominal hysterectomy, which surgery was carried out on September 15, 2012.

Abnormal leakage

And on September 26, 2012, about 10 days after the teacher was discharged from hospital, she developed an abnormal leakage of urine and she also felt severe pain around her groin area. She was readmitted at the government hospital but later referred to other higher-level hospitals.

The teacher lodged a complaint of malpractice with the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Health. Two doctors were assigned to examine her and the two doctors established that her ureter had been cut during the operation. In March 2013, the teacher was transferred to Pretoria Urology Hospital in South Africa where she was diagnosed with vaginal fistula, which, to the doctors, occurred as a result of the initial surgery to remove her uterus. Specialised surgery was then carried out to mend the vaginal fistula.

Unknown persons

Court also observed that the qualifications and names of the person who carried out the initial surgery were unknown, on account of the failure or omission to write such details on the patient’s medical records.

The patient’s file did not have the pre-operation, operation and post-operation notes. It was more than likely that the records of the surgery were deliberately omitted in the trial bundle as they had incriminating evidence and therefore could not support the defense that the Attorney General planned to put forward.

The patient’s medical records, further, did not contain any entry evincing counselling of the patient.

Court, following these undisputed facts, framed the issues for assessment and interrogation as follows;

1) Whether the performance of the operation on the patient was negligent

2) Whether the doctors were negligent during the post-operation care of the patient

3) If negligence is proved, whether the patient suffered damages as a result of such negligence

4) The quantum of damages suffered

Legal principle

For negligence to be proved court relied on the legal principle that the injury caused was not too remote to have been foreseen; that the surgeon could have foreseen the reasonable possibility of his conduct causing injury to his patient and would have taken reasonable steps to guard against such injury, which steps he failed to take.

And for the claim of negligence to succeed, the teacher had to prove, on a balance of probabilities, that the injury and loss she suffered was as a result of the wrongful act or omission attributed to the fault of the surgeon, either in the form of wrongful intention or negligence. The onus was also on the teacher to prove causation or causal connection between the wrongful act allegedly committed and the damages or losses she suffered. The applicable test here is the “but for” criterion.

What is of fundamental importance is whether what happened would have happened, but for the unlawful actions or omissions of the surgeon. The question to court was whether the teacher would have leaked urine if she did not sustain injuries in the course of the surgery. It was not in doubt that the complications that the patient suffered from, that is the leakage of urine and all its effects arose from the surgery performed on the patient.

Clearly the surgeon owed the patient a duty of care preoperatively, during and after the surgery. To court a medical practitioner is expected to exercise the degree of skill and care of a reasonably trained practitioner in his or her field.

When assessing such reasonableness, court will have regard to the general level of skill and diligence possessed and exercised by members of the branch of medicine to which the concerned medical practitioner belongs. To court experts are not guarantors of what they say or do; surgeons should not promise a cure or 100 percent success to their patients as this will not happen all the time.

Testimony

Two of experts testified in this case included one a professor of obstetrics and gynecology, who testified for the complainant and a gynecologist who testified for the Attorney General.

To court an expert is required to assist the court to lay a factual basis for his or her conclusions and to further explain to court his or her reasoning.

An expert should not usurp the function of court but present the necessary scientific and objective criteria to the issues raised. An expert’s opinion should be underpinned by proper and logical reasoning, in order for court to assess the cogency of the opinion. Without any reasoning, then the opinion is unreliable. Court is not bound to swallow, hook, line and sinker, the views or opinion of an expert nor is court a rubber stamp of an expert’s opinion.

To that extent, court is not expected to blindly accept the assertion of an expert without full and convincing explanation. The facts upon which an expert expresses an opinion must be capable of being reconciled with all other evidence adduced.

To be continued...