Prime

Katanga murder case: How Nkwanzi ran out of runway

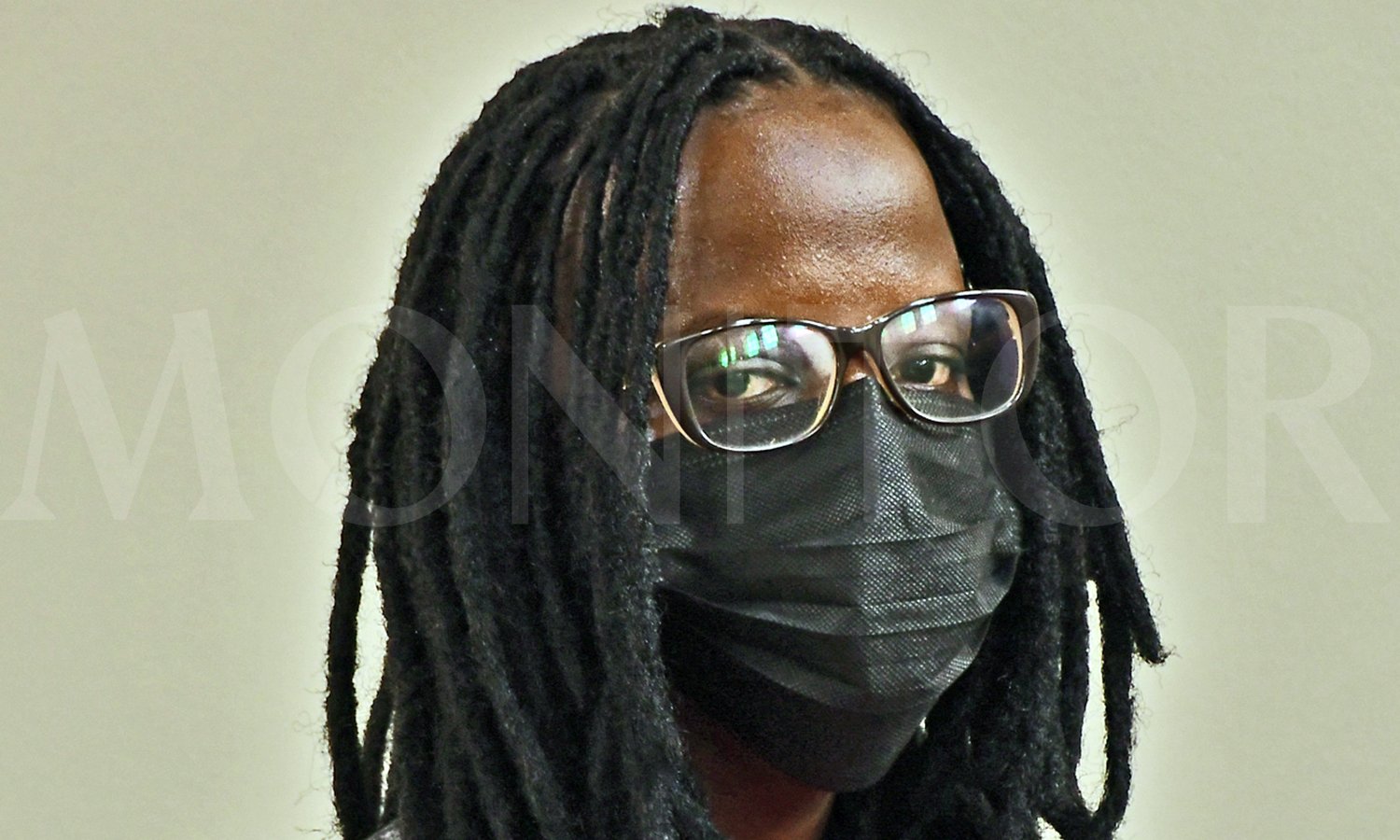

Ms Martha Nkwanzi, daughter of the late Henry Katanga, at Nakawa Chief Magistrate’s Court in Kampala on January 10, 2024. PHOTO/ABUBAKER LUBOWA

What you need to know:

- The murder case of Henry Katanga was always going to be bogged down in a fog of both legal gymnastics and manoeuvring, but such attempts didn’t save Martha Nkwanzi from appearing in the accused’s dock after the Nakawa Chief Magistrate’s Court had run out of patience and issued a warrant of arrest for her. In this explainer, Monitor’s Derrick Kiyonga explores why the issuance of a warrant of arrest for Nkwanzi, who stands accused of tampering and destroying with evidence at the crime scene, was inevitable.

Of the five people accused in the November 2, 2023 murder of businessman Henry Katanga, only two—his daughter Martha Nkwanzi, who is accused of tampering with evidence at the crime scene, and wife Molly Katanga, accused of murder—had proven elusive.

It was last November when the Office of the Director of Public Prosecution (ODPP) formally brought charges that immediately had Henry’s other daughter—Patricia Kakwanza—caught in the crosshairs alongside Dr Charles Otai and George Amanyire.

So why were both Molly and Nkwanzi at large?

Armed with medical reports, their lawyers have insisted that Molly has been undergoing surgery at International Hospital Kampala (IHK) and Nkwanzi is still recovering after giving birth last November. This, however, is a case of high emotions, with Henry’s side perceiving every delay to bring Molly, the key suspect, in court with suspicion.

When Molly didn’t appear during the first court sessions late last year, Henry’s supporters—with the help of the police—stormed the IHK’s Intensive Care Unit (ICU) where she was undergoing medical treatment. This forced Molly’s legal team led by Kampala Associated Advocates (KAA) to petition Principal Judge Flavian Zeija, imploring him to invoke his constitutional powers to stop police from interfering in her medical treatment.

“Upon police officers noticing that they are being recorded, Constable Mageni confronted our client’s next of kin and demanded the deletion of the recordings. Our client’s next of kin refused to delete the recordings and the police officers tried to arrest him on allegations that he was an obstacle to the administration of justice,” KAA wrote.

How about Nkwanzi, what had kept her away from the dock?

Although it has been easy for defence lawyers to explain the absence of Molly, who they say has undergone several surgeries for scalp psoriasis in a bid to recover from the wounds she allegedly sustained from the fight with Henry, it wasn’t easy to do the same in respect to Nkwanzi.

Initially, the line the defence lawyers told Nakawa Court Chief Magistrate Elias Kakooza was that she was recovering after giving birth. Yet Kakooza has been issuing criminal summons for both Nkwanzi and her mother, regardless. These summons are applied for by the prosecutor when an accused person doesn’t appear in court where he/she has been charged.

Are criminal summons strictly issued to the accused?

Not necessarily. There are scenarios in which it’s not possible after the exercise of due meticulousness to serve the accused personally, in which case, the law says, service of the summons may be affected by leaving the duplicate of the summons for the accused with an adult member of the family or the accused’s servant, who normally resides with him, or by leaving it with his employer.

“The person with whom the summons is left, if so required by the process server, must sign the receipt of it on the back of the original summons,” the Magistrates Court Act (MCA) says.

It’s not only individuals that can be issued with criminal summons because Section 49 of the MCA widens the scope to include incorporated companies or other body corporations. In such instances, the MCA says criminal summons might be effected by serving it on the secretary, local manager, or other principal officer of the corporation or by a registered letter addressed to the chief officer of the corporation.

“Service of criminal summons on a body corporate can be done by sending the summons by registered mail addressed to the chief officer of the company, secretary, local manager, or other principal officer of the company. These officers of a company are deemed competent to plead on behalf of the company,” the MCA says.

Do criminal summons have both bark and bite in Uganda?

Although issuing criminal summons is one key practice in Uganda’s criminal justice, a cross section of accused persons have intentionally disregarded some, citing flimsy excuses. For instance, in 2016, there was a standoff between the prosecution and Aaron Baguma, the former Divisional Police Commander (DPC) of Central Police Station in Kampala, who was at the time facing murder charges.

From 2015, Baguma had dodged appearing in court for formal arraignment alongside seven other people for allegedly killing businesswoman Donah Katusabe at Pine car bond in Kampala in October 2015. In this case, Prosecutor Jonathan Muwaganya had told the court that in murder cases, they don’t normally ask for the court to issue summons in case an accused hasn’t appeared; instead they apply for a warrant of arrest.

“Ordinarily, we don’t even issue criminal summons when it comes to murder cases. I think it is now prudent that a warrant of arrest be issued by this court,” Muwaganya said before Jamson Karemani, then Chief Magistrate at Buganda Road Court, issued the warrant of arrest for Baguma. Karemani then proceeded to say thus: “We have seen police officers who are at a higher rank than this one coming before this court. So, on September 1, 2016, the IGP or any other person should bring that person to court.”

Baguma didn’t wait. With the media away, he was smuggled into the court and charged but the ODPP later withdrew the charges.

So is it accurate to conclude that Nkwanzi ran out of runway?

In a sense, yes. In the Katanga murder case, Jonathan Muwaganya, the chief prosecutor, pressed Kakooza on Monday to issue the warrant of arrest for Nkwanzi, saying she hadn’t justified her stay away from court.

A warrant of arrest, in Ugandan laws, is an order issued by a magistrate and bearing the seal of the court. It is directed to police officers or any other person and commands the arrest of the person named in it, who is accused of having committed an offence, named in it.

Even without a warrant of arrest, it should be noted that the Police Act gives a police officer power to arrest an individual if he or she has reasonable cause to suspect that the person has committed or is about to commit an arrestable offence.

Nkwanzi’s lawyers led by MacDusman Kabega, Bruce Musinguzi, and John Jet Tumwebaze didn’t want the warrant of arrest to be issued, saying she was convalescing at Roswell Hospital, in Kampala, following childbirth. Muwaganya wasn’t having any of it. He argued that the lawyers were just relying on tittle-tattle, and insisted on the necessity for Nkwanzi to be arrested.

“But that somebody went to a medical facility a month ago for the headache and abdominal pains that she had then among others cannot be used as sufficient grounds today in January to explain the disobedience,” the chief prosecutor in the case successfully opined.

It was clear that Nkwanzi, unlike her mother, was bound to be in the dock sooner rather than later. Indeed, she duly handed herself over to the State on Wednesday, supposedly fearing that she could be humiliated with a forceful arrest.

“On January 8, the State did apply that the suspect should be arrested to appear in court to take a plea and prayed for warrant of arrest. Much as the warrant of arrest was issued and signed by court, she has appeared to hand herself into court,” Kabega told Kakooza on Wednesday.

What are criminal summons?

They are legitimate court orders that bear the court reference number, signature, and seal of the issuing court, indicating the allegations against the accused, as well as the time and date of appearing.

Section 44 (1) of the Magistrates Court Act (MCA) stipulates that every summons must be in writing, prepared in duplicate, signed and sealed by the magistrate or such other officer as the Chief Justice may from time to time direct.

“... Every summons must be directed to the person summoned and shall require him or her to appear at a place, date, or time indicated therein before the court having jurisdiction to inquire into and deal with the complaint or charge,” Section 44 (2) reads, with Section 44(3) adding that summons must also state shortly the offence with which the person against whom it is issued is charged to let the accused know and prepare for the charge he or she is being obliged to answer.

Every summons, section 45 (1) of the MCA states, must be served by a police officer or an officer of the court called a process server. Summons must be served to the person to whom it is addressed personally but the section states, if practicable, “the summons is served on the accused by giving him a duplicate of the summons and in practice, he must sign the original copy of the summons,” the MCA says.