Prime

Makerere intake reveals regional inequality

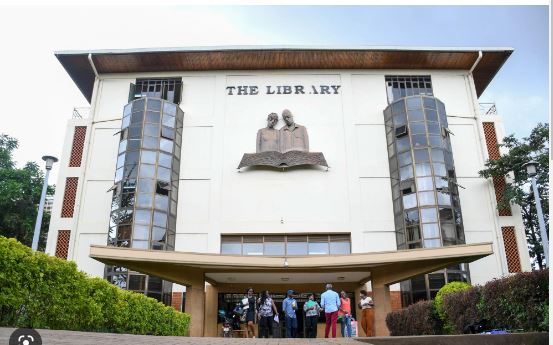

Makerere University students jubilate during the 70th graduation ceremony in 2020. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- The capital, Kampala, and its neighbouring Wakiso and Mukono districts – which together constitute Uganda’s most urbanised and wealthiest metropolis – contribute 20 percent of the 15,000 self-paying students.

Makerere University’s intake of new students on private sponsorship for the 2023/24 academic year shows widening regional and economic inequality, according to our analysis.

The capital, Kampala, and its neighbouring Wakiso and Mukono districts – which together constitute Uganda’s most urbanised and wealthiest metropolis – contribute 20 percent of the 15,000 self-paying students.

There are 146 districts and cities in the country, and nineteen of those, by our count, have sent 20 or less students each to study at Uganda’s largest and oldest university funded by tax payers.

Ssembabule, Buvuma and Kalangala island districts, and Luweero, the epicentre of the war that brought the present government to power 37 years ago, are the four districts in central Uganda with the least representation in the admissions.

Almost all districts in Karamoja, a semi-arid north-eastern sub-region rife with gun violence and cattle raids, each have under 15 students admitted for undergraduate studies at Makerere University on private sponsorship.

The other underrepresented districts are those in northern and eastern Uganda, which are regions named in Uganda Bureau of Statistics (Ubos) reports as the poorest in the country.

A similar gulf of inequality was manifest in students’ admissions at public universities on government sponsorship.

There are slightly over 1,500 more girls than boys picked on private sponsorship, continuing a pattern reversal where 52 percent of Makerere’s 13,221 graduates this year were women.

Uganda Women Network (UWONET) chairperson, Ms Rita Aciro, and Ms Sarah Opendi, the leader of Uganda Parliament Women Association (UWOPA), were cautious yesterday in celebrating the changing fortunes for the girl-child, propelled to university admission with a free add-on of 1.6 points.

Ms Aciro said the gender shift reflected a portrait of a Uganda where women outnumber men, and a rising number of girls staying in school longer instead of marrying early.

“However, are they (educated women) getting employed?” she asked, spotlighting unemployment headache that is gender-neutral and most prevalent among the young.

The State Minister for Relief and Disaster Preparedness, Ms Esther Anyakun, who is the Nakapiripirit District Woman representative in the 11th Parliament, linked the poor academic showing of her native Karamoja to insecurity prevailing in the sub-region.

“The government should first address the issue of insecurity since it also contributes to the school drop-outs [and poor performance] in the region,” she said.

The number of private students Makerere has admitted for the new academic year, which starts on August 19, is the highest in its history by 2000.

Thousands more of students have been admitted to study humanities than sciences, contrasting with the government enforced science policy being championed by President Museveni who in 2022 incentivised scientists in government employment by tripling their pay.

Asked if the admissions show failure of the science promotion policy, Dr Monica Musenero, the minister for Science, Technology and Innovation, said more students applied for arts on private because the government sponsorship was skewed in favour of sciences.

She said more science students would have been admitted has the students’ loan scheme, which the government has frozen for this academic year over budget shortfalls, was running.

“Our aim is to ensure that [investing in] one scientist can create jobs for many people,” Dr Musenero said.

The minister said a look at the admissions list may show regional imbalance but, without details of the origin districts of selected students, it is premature to conclude because they could be children of the rich from other regions huddled in metropolitan Kampala for jobs or other opportunities.

However, leaders of schools and teachers’ association argued that majority learning institutions upcountry have fewer teachers, less facilities and most either lack laboratories or reagents for practical science lessons, explaining poor performances in the subjects.

“The admissions are a reflection of how students performed [in A-level exams] and this should be a serious lesson to the government because it is the government’s obligation to ensure that all Ugandans attain all levels of education,” said Mr Filbert Baguma, the general-secretary of Uganda National Teachers’ Union (Unatu).

He called for national soul-searching about inequality in the country, especially Karamoja and ask “if the region has A-level schools, are their teachers, do we have laboratories and other facilities”.

“If we are to solve the problem, we must address the issue of access to schools, availability and deployment of teachers,” Mr Baguma said.

Mr Hasadu Kirabira, the national chairperson of the National Private Education Institutions Association (NPEIA), said the low number of students admitted to study sciences corresponds to the government’s limited investments.

“… you cannot speak about promoting science in schools when the laboratory chemicals [for science practical lessons] and apparatuses are still expensive,” he said, calling for higher budget allocation to the education sector.

Additional reporting by Busein Samilu and Peter Sserugo