Prime

Rising kidney disease burden: Navigating prevention, cure

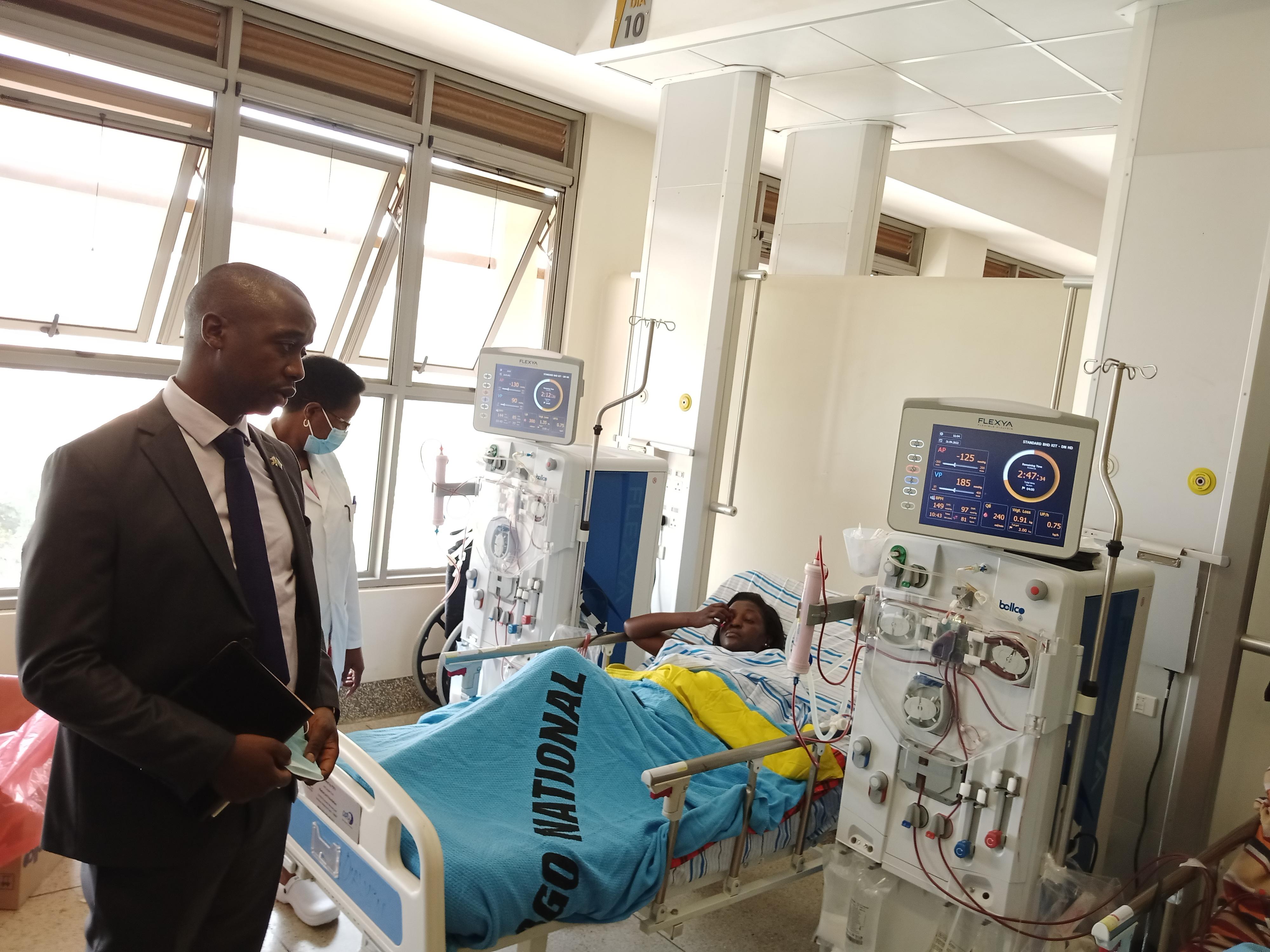

The chairperson of Parliament’s Health Committee, Dr Charles Ayume, and the director of Mulago Hospital, Dr Rosemary Byanyima, chat with a female patient at the dialysis unit on September 21, 2022. Photo | Tonny Abet

What you need to know:

- Dialysis is a medical procedure that relies on a specially designed machine to remove waste and extra fluids in one’s blood when the kidneys cannot.

- The Buikwe resident suspects he got kidney failure because of the medicine he has been taking.

Hussein Kassim, a kidney disease patient from Buikwe District, travels twice weekly to Mulago National Referral Hospital for dialysis. The hospital is some 57 kilometres away from his home.

“I started dialysis in January 2022,” narrates Kassim while on a dialysis session at Mulago hospital kidney clinic. “I stopped a bit but when the condition deteriorated, I started again.”

Dialysis is a medical procedure that relies on a specially designed machine to remove waste and extra fluids in one’s blood when the kidneys cannot.

The Buikwe resident suspects he got kidney failure because of the medicine he has been taking.

“I have been taking medicine for diabetes for 20 years. After diabetes, I developed high blood pressure,” he adds.

Like many Ugandans, Kassim cannot go past the level of dialysis and get a kidney transplant in a foreign country, which would relieve him from the burden associated with going for dialysis.

“If there was money, I could have done the transplant. The service (dialysis) here is excellent. I pay Shs200,000 per visit,” he says.

This payment excludes what he spends on medication and transport. The cost of dialysis varies from one facility to another depending on the severity of the kidney disease, the type of machine in use and the availability of waivers for patients.

Some (private) health facilities charge around Shs500,000 per session amid requirement to make an initial deposit of Shs1 million to Shs2 million by some hospitals, according to information from patients and doctors.

The management of Mulago hospital says they charge patients to get money for maintaining equipment and sustainability due to limited funds from the government.

According to kidney specialists, kidney transplants costs more than Shs100 million abroad and after a transplant, a patient needs to spend a lot more money to buy drugs to sustain the new kidney, which may cost at least Shs2 million a month.

“Owing to the costliness of kidney transplants, many patients in Uganda opt for haemodialysis, a process of using a machine to clean the blood of the waste products,” says Dr Peace Bagasha, a kidney specialist at Kiruddu Hospital.

James Walugembe, 65, another kidney disease patient from Nakawa in Kampala, says he has been on dialysis since April 2013.

“Quality of [dialysis] services have been improving since then. We need steady flow of materials, reduction in the cost of dialysis,” he says.

“I was discovered to be having kidney failure in India in 2012 where I was recommended to get transplant from there. But I decided to turn it down,” he adds.

Kassim and Walugembe form part of the rising cases of kidney disease in the country, amid limited number of facilities to get care and high charges that many may not afford.

According to a 2022 report titled ‘Global Dialysis Perspective: Uganda,’ which was published in the scientific journal Kidney360, the prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in Uganda ranges from two percent to seven percent, and up to 15 percent among patients with HIV or hypertension.

“Kidney disease in Uganda is increasing and is among the top 10 causes of death, with a case fatality rate of 21 percent among patients admitted with CKD,” the report reads.

Dilemma

Dr Robert Kalyesubula, a kidney specialist and the president of the Uganda Kidney Foundation (UKF), an organisation for medical doctors and nurses working with kidney disease patients, says 90 percent of patients with kidney failure are struggling to access care because of the high cost and few facilities.

“So the situation in Uganda is very dire. Dialysis costs about Shs1 million a week and is way out of reach for most Ugandans,” he says.

He adds: “We know that six percent of adults [in Uganda] have kidney disease that might require them to actually receive support. And about, 0.1 percent of adults need dialysis.”

There are five stages of kidney disease and it is usually those at end stage that are required to undergo dialysis or get a kidney transplant, reveals Dr Kalyesubula.

“If you look at it, about 4,500 individuals need dialysis but only 200 are getting it. The rest die, unfortunately. Out of every 100 that need dialysis, only around five or 10 can afford it even in government [hospitals],” he adds.

The expert advises the government to expedite the plan to introduce universal health coverage.

“The best way to cater for dialysis is by introducing universal health coverage, that is the only difference that is in Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda, so that there is universal health coverage,” he adds.

“The major drivers of kidney diseases are actually non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic use of drugs such as anti-retroviral therapy, infections, and then sometimes cancers,” Dr Kalyesubula says.

“So, prevention really relies on taking a personal interest. One, looking at our lifestyles, we should be able to do exercise. We should watch what we eat, particularly we need to eat a healthy diet which is full of vegetables,” he adds.

The kidney specialist advises people to take low salt in food, go for kidney checks and avoid excessive consumption of alcohol.

Dr Joseph Ogavu Gyagenda, a kidney specialist, and Dr Jimmy Opigo, the manager of the National Malaria Control Programme, also reveal that hospitals are registering increases in Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) exacerbated by delayed treatment and dehydration in malaria patients.

“Children, adults and pregnant women are presenting with kidney complications. Studies done in Uganda indicate that between 30 and 45 percent of malaria patients get some degree of kidney injury,” says Dr Gyagenda, a specialist at Northpark Specialist Hospital in Wakiso.

Among the interventions, Dr Kalyesubula also reveals that the country has started a six-month course for qualified nurses and medical workers who want to specialise in running dialysis centres.

He says over time, the number of dialysis centres have increased to around 15 in the country with about 120 dialysis machines in place.

“Before we started training here, we have a few individuals running the dialysis units and the nephrology practice. These were actually trained from outside countries,” Dr Kalyesubula reveals.

The trainees in Uganda gain practical skills when in placement in Mulago hospital, Kiruddu Hospital, St Francis Hospital Nsambya and BHL dialysis clinic in Kampala.

“Having finished the course, now they are ready to go to the field to ensure that Ugandans remain healthy and those who are sick have the opportunity to get treated by individuals who are experts,” the president of the Foundation notes.

Dr Bagasha, who is leading the training of the technicians, reinforces Dr Kalyesubula’s call.

“We (medical workers/dialysis technicians) need to talk to people about their kidneys because when we reach dialysis, that is the endpoint. We need to prevent,” she notes.

“These specialist nurses should remain in the dialysis units and not be moved to other units [as it is the norm] as this will kill their morale. You can’t run a dialysis unit without nurses,” she advises hospital directors.

Course trainers also advised the hospital directors to contract these nurses and technicians to increase efficiency and quality of care in the operations of the dialysis centres.

Still in the 2022 report titled ‘Global Dialysis Perspective: Uganda,’ in addition to challenges in mechanical infrastructure, such as dialysis units, human resources are equally inadequate, with only 14 formally trained nephrologists (11 adult and three paediatric) for a population of about 45 million people.

However, Dr John Baptist Waniaye, the commissioner for emergency medical services at the Health ministry, says the government has over the years seen marked improvement in care for kidney patients. He says more specialists have been trained and new care centres opened in the country.

“In 2012, Uganda had only two nephrologists (kidney specialists] and now the country has 14 nephrologists,” he notes.

“Uganda now has 15 dialysis centres, the latest dialysis unit was recently opened up at Lira Regional Referral Hospital and this was opened up with the support from government of Uganda,” he adds.

Mr Joshua Ojambo, a director at BHL Healthcare Limited, said their firm is working with the Health ministry to establish regional kidney centres. He says plans are underway for their company to construct a 60-bed facility that will provide kidney care in the country.

Dr Kalyesubula also says the kidney foundation has plans to establish the Uganda Kidney Institute to improve quality and access to care.

“We are fortunate that we have already started regional centres. We have a centre in Gulu, Soroti, Mbarara and we have over 12 dialysis centres in Kampala. We have around 120 dialysis machines in the country,” the president notes. Lira Hospital management has also said they started doing dialysis.

“That [number of dialysis machines] is very little when you see the population of 45 million, because if you see a nation like Kenya, they have about 2,000 dialysis machines,” he adds.

prevalence

According to a 2022 report titled ‘Global Dialysis Perspective: Uganda,’ which was published in the scientific journal Kidney360, the prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in Uganda ranges from two percent to seven percent, and up to 15 percent among patients with HIV or hypertension. Dr Robert Kalyesubula, a kidney specialist and the president of the Uganda Kidney Foundation (UKF), an organisation for medical doctors and nurses working with kidney disease patients, says 90 percent of patients with kidney failure are struggling to access care because of the high cost and few facilities.