An illustration explaining how BLQ Football Club’s “investors” make money. PHOTO/COURTESY

|National

Prime

Ugandans lose Shs60b in football Ponzi scheme

What you need to know:

- The BLQ scam leaves behind hundreds of Ugandans who had recently become millionaires.

- The supposed wealth vanished in a matter of hours as they looked on helplessly.

The last message BLQ Football Club posted on Twitter on October 12, at 11:54pm, simply read: “I’m Out!” It was accompanied by a peace emoji. There was, however, nothing peaceful about its users in Uganda losing an estimated figure believed to have breached the Shs60 billion mark.

Yet one of the scam leaders had the audacity to tell victims of the pyramid-cum-Ponzi scheme on the social media app, Telegram thus: “You Ugandans thank you, you have been fooled but I am coming with another trick after this money is over.”

The return of such scammers cannot be ruled out as Uganda has for more than two decades played host to classic Ponzi schemes built on treachery and lies. Scammers always come back and find a willing population ready to be duped of billions of shillings. The efforts of the authorities to crack down on the scammers have also been wanting, with many of the perpetrators simply getting away with it.

Most of the victims are desperate given the high unemployment in the country, while many high net worth individuals also engage in the scams given their high appetite for risk.

Monitor spoke to a female victim, who had put about Shs500,000 in the BLQ Football Club scheme. She joined the Ponzi scheme a few weeks before it shut shop. Evidently sad, the woman, who identified herself as Birungo told us that she was simply looking for more opportunities to make money. The risk, she added, was in joining late or staying for too long.

“Wait, are you going to help members get their money back or? Because as for me, mine was so little. Actually, I have made it today and I am looking for another app to invest in,” she said.

The reason as to why Ms Birungo was almost oblivious to the fact that her fingers had been burnt is because early “investors” in BLQ Football Club made rich rewards. Or so we were told. In social media platforms accessed by Monitor, “investors” who made money and pulled out at the right time or only ploughed part of the huge profits were celebrating and mocking their “greedy” counterparts, who were licking their wounds.

Lowdown on the scam

Monitor, through interviews with several former members, has been able to piece together a picture of what transpired.

Hours before the scam collapsed, the members were told to top up 20 percent of their account balances.

Three hours after the directive, the app disappeared. The Telegram chats were disabled and members could no longer comment. The teachers/mentors they sought counsel from before went underground and have not been online since. How did the victims get there?

Sometime in 2019, the BLQ scam was established in the country. The scam would eventually obtain a trading licence from Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) and some documentation from Uganda Revenue Authority (URA). The documentations were used to create a sense of legitimacy among their “nosy targets” who asked some questions.

To spruce up the con, the people behind the scam—believed to be Nigerian nationals as per various sources—told their targets that they had partners in China, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), South Africa and Nigeria. They claimed their headquarters were in the English city of Manchester.

With the con set, all the sources Saturday Monitor spoke to say the recruits were placed in one group on the social media platform Telegram. The group had 5,648 members at the time of the collapse.

Hedging bets

The scam operated like a betting site where users would put forward fixtures and predict their matches. Users would be in business if the scammers predicted that the final score in a particular football match would be 2-0 and the prediction was incorrect. Former members say even when they lost their bets, which was often, the scam baited them by compensating the money lost. The money kept coming in.

The scam had a corporate social responsibility arm that engaged in charity by reaching out to people, giving different foodstuffs as per someone familiar with their operations.

The scammers also acquired offices, including one at Kyamula near Total Energies Fuel Station on Salaama Road, Kampala. By October 13, their premises were marked “permanently closed.”

In promotional photos and videos seen by Monitor, the supposed employees of the scam are filmed looking down to avoid direct eye contact with the camera. Only one video recorded hours to the collapse of the scam has an unidentified man assuring the members of the viability of the project.

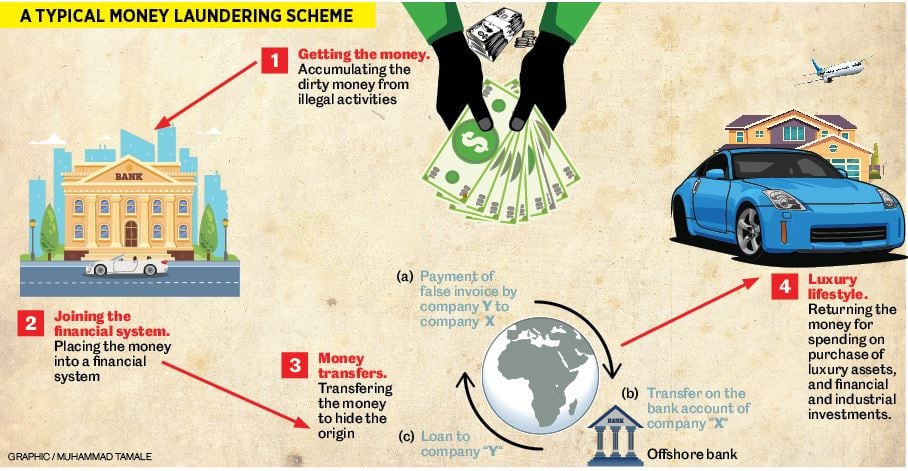

ALSO READ: Why we can’t curb money laundering

For a long time, the more than 5,000 people were in the same group and would access the opportunities presented by the scam jointly. Then they started fragmenting the teams. Various groups, including normal, VIP, VVIP and Premium, were introduced. For example, to leave the normal group and join the VIP, one’s account had to have a balance of more than Shs1m. Those who had that money and more would automatically be upgraded to the exclusive clubs, which had more privileges.

Those on the VIP platform would get five percent more in profit compared to the rest on the normal platform. The members had three matches a day. The portal would be opened at 10am, with the first game that would end around 2pm. This would be followed by another game that would occupy the period between 4pm and 8pm. The third game was exclusive for the VIP and other top money groups.

“These men have taken off with Shs60b or more. For example, I had Shs25m, which I lost. But we had one guy called Ambrose, who had more than Shs365m. He was the single biggest investor I knew,” Miles, a former investor, told Monitor.

We understand one VIP section had 687 “millionaires” before the scam imploded. Many individuals, according to corroborated evidence, lost on average of Shs100m. There is a couple that days before the collapse, invested Shs30m each.

Mentors go AWOL

Some of the teachers/mentors went by names such as Mira Bel and Amina Jones. The latter was the director and owner of the Ugandan project. Jack and Bruno were mentors, completing the official hierarchy known to many.

Attempts by Monitor to speak to the mentors were futile. The calls on the numbers we sourced did not go through. The mentors/teachers kept their true identities hidden using the privacy features of the Telegram app.

A screenshot showing a chat between “an investor” and a BLQ mentor/teacher. PHOTO/COURTESY

While red flags in the scam were clearly visible, many victims confessed to us that the abnormal profits were blinding.

“What you need to know is that the names of those people I have given you are not Indians, whites, Chinese or Arabs. They are Nigerians who posed as people of other nationalities. What I know is that they have moved to Burundi to continue with their scam,” a victim who requested anonymity, told Monitor.

While the mentors/teachers kept their identities, Monitor has learnt that some of the people in hot soup are members who recruited others. These had even formed Whatsapp groups in which they mobilised their recruits to get richer. One such “administrator”, who persuaded others to repeatedly invest, has since disappeared. One person simply identified as Pastor lured hundreds of people.

Warning signs

It all started with difficulty to withdraw funds from the platform. The deal, however, was too sweet. While many were met with pending messages when they tried to withdraw the funds, the other members continued to deposit. More people also kept buying in.

“We would withdraw the money from the BLQ and it would reflect on either our MTN or Airtel accounts in 24 to 48 hours, but this month, things changed,” a former investor told Monitor, adding, “They started saying the people are many and money would come in slowly. You would, for example, withdraw money on Monday and receive it on Wednesday or Thursday. It would take three to four days.”

The former “investor” told us they joined after “a friend of mine came to me with a screenshot showing how she had invested.” The former investor’s lady friend had an account with “a lot of money and she told me to join using a link.”

They were told that “if you joined using a link, that person gets a bonus of the money you have put forward.” So the former investor “first put Shs10,000 and then realised it was making money.” The former investor says they “withdrew Shs20,000 and received 19,000.” It was then that they “realised I could put money and make a decent return.” So they deposited “all my business money for last week … in that BLQ [and] so far I had about Shs200,000 on the platform.”

The BLQ scam leaves behind hundreds of Ugandans who had recently become millionaires. The supposed wealth vanished in a matter of hours as they looked on helplessly.

Genesis

In its early days, Monitor can reveal, the scheme targeted mainly young people, especially university students, who went ahead to recruit their relatives in the seemingly “lucrative scheme.”

To perfect their con, the BLQ team also regularly shared motivational quotes to ensure the users remained hooked. They posted a Maya Angelou quote on their Twitter platform on August 4, which read: “Whatever you want to do, if you want to be great at it, you have to love it and be able to make sacrifices for it.”

Sacrifices were indeed made at great cost. In urging “every investor to get involved in the great cause”, BLQ marketed itself as “a legal and stable football hedge fund investment platform.”

BLQ also bragged that it has “a business licence issued by the Ugandan government” and another “business licence issued by the British government.”

Questions abound how Ugandan authorities allowed the scheme to operate for such a long period, moving around huge sums of money without any concern.

In January, Mr Sydney Asubo, the executive director of the Finance Intelligence Authority (FIA) told legislators that Uganda risks being blacklisted by the Financial Action Taskforce (FATF) if the government does not tackle money laundering by May 2022. Several efforts were made to keep Uganda off the list.

The last three decades have seen a pile-up of Ponzi and pyramid schemes and other such get-rich-quick schemes that have defrauded Ugandans of billions.

Customers and investors, who have pegged their livelihood and expectations of a secure financial future, have been left at the hands of the frauds.

Businesses, individuals, communities have been ruined adding on the already devastating poverty statistics and suffering in the country. There are evident regulatory and supervisory failures, with State agencies only coming to put out the fire when it’s too late.

Ugandans have also been warned about the operations of Crown Football, UG football and E Cairo.

The fraudsters are leveraging, among other things, the latest technology and using the Internet to mask or lend credibility to their schemes and dupe investors into putting their money in their scams. Given the limited information available on new or latest technology, potential investors do not have much information to guide their decision making but many are driven by poverty and greed.

About Ponzi schemes

Ponzi schemes employ a trick of picking money from one client or “investor” and giving it to another person until they run out of new investors or simply when the fraudsters disappear or are compelled to conclude the scheme by authorities. In a Ponzi investment scheme, investors are rewarded high returns from their own money or the money paid by other investors instead of relying on profit earned from the ‘investments’, which don’t exist.

Past cases in Uganda

Dunamiscoins Resources Ltd

The case of Dunamiscoins Resources Ltd was registered under the laws of Uganda (80020001481676) on January 21, 2019, as a private company limited by shares. It operated legally within the country’s financial system, with known head offices on Plot 11A Rotary Avenue, Kampala. Out of the blue, in December 2019, both customers and staff woke up to a rude shock that the company was broke.

The staff could not make the daily payments and the customers could not receive their money, which was due. Dunamiscoins is reported to have defrauded 2,500 people of Shs20 billion.

Each of the depositors was promised a 40 percent interest on their deposits after 21 working days. The early investors benefited and received the promised 40 percent interest on their investments. By November 2019, the company increased interest to 50 percent on each deposit. Police and other authorities launched investigations and two suspects— Mary Nabunya and Simon Lwanga—were arrested and charged at the Law Development Centre court and sent on remand.

Dunamiscoins Resources Ltd was founded by Nigerian and Ghanaian nationals in 2019. The firm had four local directors—Nabunnya, Lwanga, Susan Awon and Faith Makula. It enlisted thousands of Ugandans as customers, who in turn injected billions of shillings before the establishment suddenly went bust within a year of opening business. The beneficial owners of Dunamiscoins are Kingsley Egbe and Johnson Frank (Nigerians), Isaac Akwete (Ghanaian), a one Dr Mike (nationality unknown) and Awon. Their whereabouts remain unknown.

The case of COWE

Starting 2007, conmen operating under the cover of the non-profit organisation ‘Caring for Orphans, Widows and the Elderly’ (COWE) defrauded unsuspecting Ugandans of billions of shillings. Most of the victims were the elderly and poor women in villages. The trick used was to ask them to invest and receive high returns from donors, who would rely on the victim’s demonstrated commitment to help them fight poverty.

ALSO READ: Unpicking the ‘art’ of washing dirty money

The organisation held an NGO licence, but operated as a bank or microfinance institution and held marketing campaigns across the country, including radio adverts. More than 3,000 people invested by mortgaging their property like land to banks to cash in on the astronomical 54 percent profit promised.

In 2006, Bank of Uganda tried to intervene by freezing the organisation’s account, but the fraudsters successfully challenged this move in the High Court by claiming they had not been given a fair hearing.

This gave them an opportunity to clean the accounts and disappear. A decision by the appeals court three years later, in 2009, was too late. Many of the victims reported to the police, but COWE directors were never brought to justice. Ten years later after the scheme was started, at least four victims had committed suicide directly linked to the scam. Worse, many of the victims have been incarcerated over loans they failed to repay to commercial banks and microfinance entities.