Prime

What Abu Mayanja hoped Uganda would shape into

Abu Mayanja (right) with his daughter. Mayanja believed that election laws should ensure that the people’s choice of a candidate for any governing body as upheld. PHOTO | COURTESY

What you need to know:

- In the second instalment of the serialisation of Prof ABK Kasozi’s book on Abu Mayanja, the historian sketches a portrait of how the subject of his study envisaged the postcolonial state in Uganda.

Abu Mayanja wanted Uganda to be a liberal democracy in which citizens’ rights and liberties were assured by a government freely constituted by the people through regular and fair elections and in which the people recognised and defended the state and its government.

For him, the pillar of this democracy was the supremacy of the people over their rulers. He lived and spent most of his political life searching for an ideal liberal democratic Uganda. The Constitution would be an agreement between the people and the government for establishing and maintaining democratic political behaviour, permitting only elected people to make national or local laws.

Mayanja believed that election laws should ensure that the people’s choice of a candidate for any governing body—Parliament or local councils—was upheld. Indeed, since the establishment of the postcolonial state, many Ugandans have tried, in vain, to search for a liberal democratic state in their homeland.

On the social level, Mayanja envisaged a just postcolonial society in which all ethnic, religious, racial and gender groups lived in mutual respect without enforced unity into one mega tribe or a need to give up their unique traditions and customs. He strongly felt that unity did not mean uniformity.

To guarantee participation in the governance of their country, Mayanja preferred to constitute responsible governments (both central and regional) elected by the people. He advocated a moderate Executive branch, arguing vehemently against dictatorship, “whether local or foreign.”

Mayanja argued that the best way to moderate government power was to effectively divide powers across the three branches of government (Executive, Parliamentary and Judiciary). However, he believed that Parliament superseded the other branches because it was the “watchdog of the people.”

Although he favoured a moderate government over a dictatorship, he thought that the government should be strong enough to govern while sufficiently moderate to guarantee individual rights and liberties.

Role of the state

For Mayanja, the state’s role, and, therefore, major function, was to guard and protect life, individual rights, liberties, and freedoms. These included the basic rights to live freely, to own property, to freely express one’s views, to have freedom of association and to select one’s leaders through regular and fair election.

Further, he thought Ugandans should have other various derivative freedoms such as freedom from arbitrary arrest or detention without trial, and the freedom of movement within and outside the country. He believed that the second major function of the state, through its government, was to enhance the welfare—and, therefore, the happiness—of its citizens. As he often pointed out in the press and in Parliament, the justification for asking the colonialists to go was that they denied Africans the freedoms and rights the latter deserved.

However, to his disappointment, postcolonial African governments took away their citizens’ freedom, which even the colonial state had never dreamed of curtailing. On one occasion, he said in Parliament: “This government of ours which is directly elected by the people is taking away even the slightest iota of liberty which the imperialists did not expect to take away.”

While debating proposals for the 1967 Constitution, Mayanja again emphasised this point,

“…the justification for Uhuru [independence] was not only because we wanted to be ruled by black men on a purely racial principle, but because colonial rule was a bad rule in the sense of depriving us of certain things, what we considered, what we had been taught in schools were very important fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual, the right to decide who shall govern you, the right to meet freely, the right to disseminate ideas, the right to acquire the freedom of speech, the right of property and so on.”

[Adding:] “Now I want to say that although we indicted colonial rule, and that was one of the platforms because it denied fundamental human rights, nevertheless, there were many human rights which were guaranteed under colonialism, and I am very disappointed to see that there were some rights which we had even under colonialism, but which we are taking away under these proposals.”

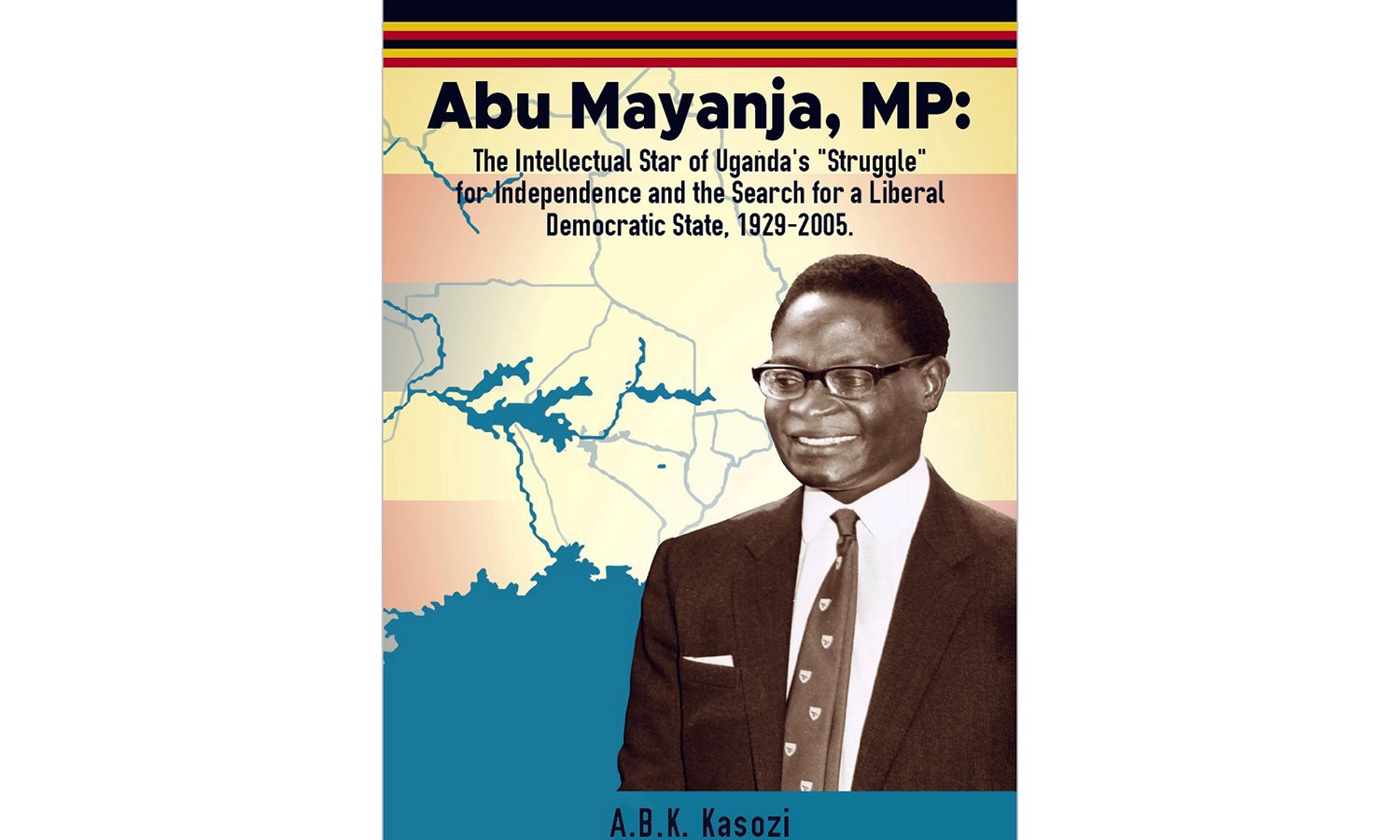

The cover of Prof ABK Kasozi’s new book on Abu Mayanja. PHOTO/COURTESY

Rule of law

Mayanja believed that while the state had the right to maintain law and order, it must do so within the law. Accordingly, the state and its workers should not escape real or vicarious responsibilities as they exercised their functions. Government agents like the police must operate within the law, never infringing upon citizens’ rights, liberties, or freedoms.

As an example, Mayanja thought that permitting detention without trial was one of postcolonial Uganda’s most unfortunate decisions, arguing that it “…eats, it corrodes into all the other rights and freedoms which we are trying to guarantee the people of Uganda under Chapter III of the proposed Constitution. Even God cannot condemn a person unheard for on the last day of judgement, angels will read out the files of each and resurrected minds will be permitted to say something. … for to deprive a man of liberty, of the right to see the sun, to hear the birds singing, to enjoy his home with his family not because a man has broken the laws of his country but because it is feared that he may do so at some future point, is absolutely indefensible.”

At the same time, Mayanja realised that individuals needed state protection to achieve their potential. For that reason, he urged Ugandans to accept the jurisdiction of the state through its government. However, he pointed out that the formation of government, especially its powers and limitations, must be agreed upon by the people in a contract called a constitution.

The Constitution

Mayanja wanted to live in a Uganda that observed and respected a national constitution, which he saw as defining (and guaranteeing) the rights and liberties of citizens in a liberal democracy.

To him, this document was the legal basis for state action, for constituting the government, for defining the relationship between the people and the government, for clarifying citizens’ rights and obligations, and for outlining the values and principles for which the nation stood.

He insisted, however, that a constitution was not a cure for every political problem. It was only a guide to political behaviour, and state managers would make it flourish or fail. Mayanja was involved in the drafting, criticising, and moderating of all Uganda’s constitutions except the Pigeon Hall Constitution of 1966.

He was the major architect of the 1962 Constitution, the main outspoken critic of the 1967 Constitution, a member of the Constituent Assembly that drafted the 1995 Constitution and an opponent of the 1995 Constitution’s amendments.

According to Mayanja, the “… underlying philosophy of our Constitution is that all men are under the law and no one is above the law.” He also pointed out that any constitution must balance the interests of the state with those of the individual. For him, therefore, “…any constitution must be built on the assumption that the state exists for the individual: i.e., for the good of the citizens. However, while providing security, the state should guarantee the liberties and freedoms of the individual.”

To achieve this goal, a constitution must balance the interests of the individual with those of the state, especially its security, for: “… every constitution attempts to resolve two apparently conflicting claims or interests.”

“It tries, on the one hand, to reconcile the claims of freedom with the interests of security. It tries to reconcile order with liberty, the state with the individual. You can use whatever word you want but basically, the basic problem which any constitution maker has to resolve is this one. ‘How do I reconcile a government strong enough to govern and to move ahead with the objectives of personal liberty and of freedom of action?’”

A united Uganda

Like Obote, Mayanja wanted to live in a united Uganda. But unlike Obote, who advocated for the total union of “one country, one President and one Parliament” based on total equality and similarity of governance structures for all regions of Uganda, Mayanja thought that a loose confederation that recognised local peculiarities was the most practical for Uganda at that time.

For Mayanja, unity did not require total amalgamation and uniformity. He thought that people of different cultures and traditions could live in one state without giving up their traditions and their ways of life. He thought that given the many diverse tribes in Uganda, unity in diversity was the most practical option for achieving consensus to work together as a nation. He felt that Obote’s goal to achieve total unity within a generation was impossible because of the diversity of the people of Uganda. The country’s various tribes did not only have different cultures but were also at different levels of social development.

Preferring unity in diversity, Mayanja felt that Uganda should aim at creating a society like that of Switzerland rather than risk becoming another Congo, where enforced unity had led to chaos. Speaking in Parliament, he said: “Mr Speaker, we have got here the opportunity to make this a happy country, to make it another Switzerland where people are united, irrespective of their diversities of origin. We have got an opportunity to build here another Switzerland, or we have got an opportunity to build here another Congo, and there is no half-way house between these two.”