Mayanja lands on his feet in Ugandan political landscape

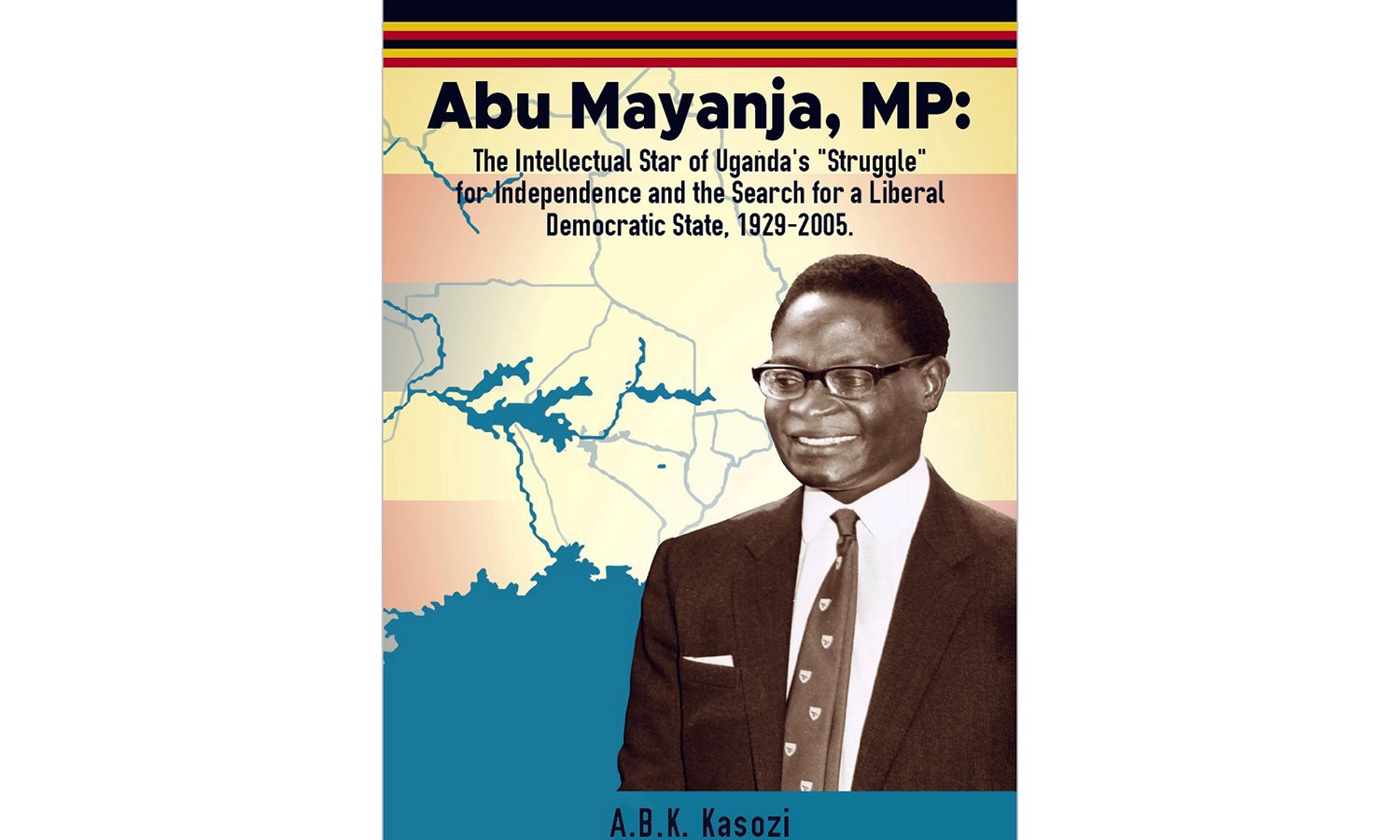

The cover of Prof ABK Kasozi’s new book on Abu Mayanja. PHOTO/COURTESY

What you need to know:

- In the first instalment of Prof ABK Kasozi’s new book on Abu Mayanja, the historian pores over the words and analyses events attributable to one of the greatest thinkers in late colonial and postcolonial Uganda.

It is evident from the sources I have been able to consult that Abu Mayanja was the intellectual star of Uganda’s “struggle” for independence and initial postcolonial efforts to build a happy, stable Ugandan postcolonial state from 1952 to 1971.

First, in most of his political activities, speeches and writings, he exhibited a higher level of understanding of the challenges that faced Uganda’s postcolonial state than his contemporary politicians.

Those Ugandan “founding fathers” politicians faced complex political, economic, and social challenges that were on many occasions, beyond their intellectual capacities to comprehend.

The political challenges included creating a participatory political system that would guarantee peace and give African people the freedom colonialism was accused of taking away, maintaining the unity and integrity of the state in the face of competing tribal and subnational forces and building mechanisms for the peaceful transfer of power.

The economic challenges included the establishment of a viable national economy, which would be a basis for unity and raising the standards of living of the people. The social challenges included the proper administration of justice and efficient delivery of public services. However, the immediate and more significant challenge was the rushed granting of independence by the colonial power. Not only did independence come before Ugandans developed political tools to manage a state but also the governance structures the colonial administration was trying to put in place were not yet consolidated. Yet the UK [United Kingdom] was in a rush to scramble out of Africa.

A combination of internal forces within the UK and the impact of World War II accelerated the pace of decolonisation in Africa faster than many policymakers had imagined or planned. Most of the educated elites, the so-called “freedom fighters” who took power from colonial officials, did not have the experience nor the intellectual capacity to understand and resolve these challenges.

As the reader will find out, Mayanja was frank about his colleagues’ low levels of understanding of issues in Parliament, often referring to them as “ignorant, monumentally dense, one-track-minded”, and so on. From 1952 to 1962, the focus of Ugandan African politicians was capturing the postcolonial state and enjoying the fruits of power.

No one had a well defined idea of the nature of the desired postcolonial state

None of the political parties that aspired to lead the country fully defined the nature of the postcolonial Ugandan state they wanted to establish after the exit of the colonial officers. For example, the Uganda National Congress (UNC) motto was “Self Government Now” without fully explaining what would follow. Although Mayanja was more informed of the problems of constructing a Ugandan postcolonial state than his colleagues, his descriptions of the state he wanted Uganda to be were articulated after Independence, especially on the floor of Parliament from 1964 to 1968. He admitted, in 1999, to a lack of thorough analysis of the type of state pre-independence Ugandan politicians wanted to establish, saying “…. there was a lot of expectations. We thought we would make a better deal for the country if we got behind the steering wheel. Independence came too soon. Sooner than we expected.”

Fifteen years later, he said, “My vision was that we would be in charge of our affairs. Many cases of abuse, shortcomings and failures were attributed to colonialism. We thought that independence would result not only in the Africans taking over the reins of government but also the economy.”

Second, unlike other politicians whose vision was limited to taking over the postcolonial state by merely “falling into things” and enjoying lucrative positions vacated by colonial officers without changing state structures, Mayanja reimagined the structures of the postcolonial Uganda he wished to emerge more clearly than the rest of Uganda’s “founding fathers” except E M K Mulira and, to some extent, Benedicto Kiwanuka.

The Uganda he envisioned

As a result, his ideas dominated Uganda’s political landscape more than any other local politician in that period. […] He imagined forming a liberal democratic state using African ideas of social justice and organisation as the foundation for building a happy, harmonious political community. He believed freedom of thought was the taproot of development and it required free minds well prepared by a broad Africanised education curriculum to succeed. He also believed that such free minds could only operate in a just society.

For Mayanja, the rule of law prevails over autocracy in a just society. He thus sought a Ugandan political community based on the consensus of citizens and the rule of law. He argued that the Uganda postcolonial state should be built on Africanised liberal democratic structures through which the people’s will superseded those of rulers. He saw the state as the servant of its citizens. Its role was to protect individual rights, liberties, and freedoms, including the right to a free life, own property and make social choices.

Although Mayanja saw government as state power, he emphasised that it should operate within the law, even in a complex process of re-establishing law and order. To achieve this aim, Mayanja preferred a moderate government—one strong enough to govern yet restrained sufficiently to guarantee individual rights and freedoms. He thus advocated for the Westminster model of government to separate powers amongst the Legislative, Executive and Judiciary branches to attain such a balance. He believed that the government’s most important function was the proper administration of justice based on laws informed by people’s concepts of the values of their society.

For Uganda, this meant that the philosophical basis of law should be African ideas of justice. To this end, he contributed more recorded parliamentary speeches and published materials and received more press coverage than any other Ugandan non-head of state of his generation.

Intellectual star

Third, he was the brain behind most of the documents produced by Uganda’s first political party, the Uganda National Congress, including drafting the party’s constitution, making its leaflets, and writing minutes of important meetings and speeches for the officials of the party. Until John Kalekezi joined the UNC, Mayanja wrote most of the party’s propaganda documents.

Fourth, as a leading member of the Kabaka Yekka, Mayanja wrote most of the ideas and documents of that organisation.

Fifth, although Mayanja never occupied the nation’s top position or political party, he was recognised by his contemporaries as a person who understood the country’s problems well and had the brains and courage to expound them. He performed well at school, and a colonial officer noted that Mayanja was the best brain the Protectorate had ever produced.

John Nagenda, a writer and journalist, pointed out, “Academically, he (Abu) was one of the brightest people of his or any other time Uganda has ever produced.” As we shall note later, Peter Mulira was of the same view.

Sixth, due to his high level of understanding of political issues of the time, Mayanja was more prolific in producing and publishing ideas concerning Uganda and African politics, especially from 1952 to 1960, than any of his contemporary Uganda politicians.

The late Ali Mazrui, who was a prominent academic at Makerere, was reported to have told a group of Makerere students that Mayanja should have been an academic instead of a politician. Both Mayanja and Mazrui were contributors to the Transition magazine, and the former protested when Obote arrested Mayanja without a fair trial. He wrote more well-argued articles in local and international publications than his contemporary Ugandan politicians.

His ideas were well received in the press, and many academics and journalists debated them in the media and other forums.

Clean record

Seventh, he was the leading brain in putting together the political coalition to which the colonial officers handed power in 1962. He linked Muteesa II and Obote at Bamunanika and designed the KY/UPC alliance that took control of Uganda in 1962. He brought Buganda and Uganda to agree to a shaky political arrangement to permit the colonial administration’s power transfer to Africans.

Eighth, he conceptualised the 1962 Constitution by making Obote and Muteesa II engage in what was politically possible at that period.

Ninth, as the minister in charge of elections at Mengo, he managed the 1962 Lukiiko [parliament] elections in favour of the KY/UPC alliance, which gave Obote the 21 parliamentary seats he needed to get power.

Tenth, when he was sent to Parliament to represent Kyagwe Northeast, he became the most articulate Parliamentarian the country has ever had. He spoke on virtually every aspect of governance. Due to his oratory and speaking capacity, a few people jokingly refer to him as Uganda’s “Edmund Burke.” There was often opposition to his ideas and personality, but, in many cases, the government used his ideas and suggestions in managing the state and drafting laws. Over his political career, he moderated or influenced law formation more than any other Parliamentarian in the same period.

Eleventh, Mayanja was never reported to have been involved in corruption because he had a cause to pursue. He believed that the aim of political participation was to enhance public service. He participated fully in Uganda’s political processes for most of his adult life. He was a Member of parliament for many years and served as a Cabinet minister in many postcolonial governments between 1960 and 1994.

While debating on the infamous “Gold Scandal”, Mayanja prophesied that corruption would lead to the destruction of the state. As the reader will find out, Mayanja was the first Parliamentarian to propose that public officers declare their wealth before taking office. He lived modestly and left no wealth except a few real estate properties.

Lastly, he was deeply dedicated to serving the nation by pursuing politics and public service as a full-time occupation.

This behaviour made him different from his colleagues who regarded politics as a part-time activity and were often referred to as “weekend politicians”. Studying Mayanja’s life can also help us understand why Uganda has failed to develop institutional mechanisms for peaceful power transfer.

In the second instalment, Prof ABK Kasozi looks at the state Mayanja wished Uganda to become, his vision for the role of the state, and more.

This book was disseminated to the academic community at Makerere Institute of Social Research on January 31, 2024 and the subject’s family hopes to launch it to the public later on.

Background

Abu Mayanja was the first Secretary General of the Uganda National Congress party, the first political party in Uganda set up on March 6, 1952 by Ignatius K. Musaazi. He became the Secretary General of the UNC in his youth and while an undergraduate student at Makerere University College, which later became Makerere University. Abu Mayanja helped Musaazi draft the Constitution of the Uganda National Congress party.