Prime

Will Museveni 6th term deliver after 35 years?

Some youth prepare to leave Entebbe airport for employment in Dubai, UAE on October 22, 2019. Photo/Abubaker Lubowa

What you need to know:

- President Museveni promised a lot in kisanja hakuna mchezo and is making even firmer promises as he prepares to swear in for another term. We attempt a quick stocktaking of his previous five terms in office.

- "I have never seen South Koreans exporting labour. The only South Korean I have seen (exported) is (former United Nations secretary-general) Ban Ki-moon. Their country is half the size of Uganda but you don’t see them (exported). I am now for the South Korean approach” President Museveni.

For the 35 years President Museveni has so far been in charge of Uganda, his manifestos have been underpinned by attention-grabbing catchlines but they don’t differ much in substance.

In 1996, when he organised elections for the first time, having ruled for an initial 10 years, Mr Museveni’s manifesto had “Tackling the Tasks Ahead” as the theme. The one of 2001 was “Consolidating the achievements”; 2006 had “Prosperity for All”; whereas that of 2011 had “Prosperity for All: Better Service Delivery and Job-Creation”.

Whereas his 2016 manifesto, which saw Mr Museveni get this ending term, had the principal theme and message as “Taking Uganda to Modernity through Job Creation and Inclusive Development”, it is the Swahili slogan of kisanja hakuna mchezo (term for no nonsense) that Mr Museveni adopted after taking an oath that captured people’s imagination, thinking things will be different from the previous terms.

Mr Museveni has always been obsessed with dragging Uganda from a principally low-income society to a competitive middle-income country, and the 2016 manifesto captured that ambition.

The World Bank classifies the world’s economies into four groupings – low, lower-middle, upper-middle, and high.

For a country to at least qualify to the lower middle-income bracket, which Mr Museveni says is his target, its Gross National Income (GNI) per capita should not only exceed the threshold of $1,036 (Shs3.7m), it should have high quality livelihoods with peace, stability, good governance, a well-educated and learning society and a competitive economy capable of sustaining growth.

In 2020, for example, the World Bank declared that Tanzania, Uganda’s southern neighbour, had been elevated from the low-income bracket to lower-middle income status after the country‘s GNI per capita increased from $ 1,020 (Shs3.6m) in 2018 to $1,080 (Shs3.8m) in 2019.

Tanzania’s elevation was a product of the country’s solid economic performance of more than six per cent real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) average growth for the past 10 years.

In 2019, while Tanzania was taking baby steps to get out of the low-income bracket in which Uganda is still stuck, Mr Matia Kasaija, Uganda’s Minister for Finance, was asked about the consequences of Uganda’s surging foreign debt and its implications on the economy.

Mr Kasaija said: “I would like to assure this country, and everyone, that our debt is sustainable in the medium to the long-term.”

Mr Kasaija dumped English and turned to Luganda, saying “… amabanja tegajja kutuziika nga bwemuwulira nti gajja kututuulira gatuzikke” (Uganda won’t be entrapped by debt like many doomsayers are predicting). His ministry, Mr Kasaija went on to brag, is full of competent technocrats who are steering Uganda’s economy in the right direction.

“We are very serious people in the ministry; we watch, we watch,” he said. “Every time a borrowing proposal is brought to me, there are certain things I must ask that officer, say ‘show me this, show me this!’ When the economy expands, businesses expand, you people earn more money; so because I tax you more, I get more money. Now I don’t need to borrow.”

Two years later, Uganda’s total public debt has swelled to $18b (Shs64 trillion) as of late 2020, prompting Mr Kasaija to admit that he has no option but to ask Uganda’s major creditors such as the World Bank and China to halt loan repayments amidst a growing default risk.

Yet when he was recently speaking to the National Resistance Movement (NRM) party’s retreat for the newly elected MPs at the National Leadership Institute (NALI) in Kyankwanzi District, Mr Museveni seemed to blame the failure to transform the livelihoods of peasants on MPs.

“Our MPs are busy in Parliament raising points of order, wasting time with points of information, etc,” Mr Museveni said. “Then after a few days in Parliament, they start flying abroad apparently to benchmark but they have sisters carrying firewood and water on their heads; they have mothers getting red eyes while cooking in too much smoke.”

The President asked: “When will the people in your villages get good houses? When will people in your villages get safe water? What are you benchmarking? I am not happy with how MPs are conducting business in that House.”

When he was introducing the kisanja hakuna muchezo chant in mid-2016, Mr Museveni, who was speaking to a group of his NRM cadres, ministers and technocrats, sketched a 16-point plan essentially aimed at “fast-tracking industrialisation and socio-economic transformation”.

Notwithstanding how strong-willed the label seemed, the points themselves were not new. Mr Museveni talked about the overbearing need for industrial expansion through foreign investment, which he claimed could be invigorated through special tax breaks, the installation of industrial parks, and the clampdown of wages.

During this term, Mr Museveni has commissioned operations of several small-medium manufacturing and assembly plants across the country, saying they will curb unemployment among the young people.

However, this has not stemmed the number of Ugandans who are pouring into the Middle East to work as housemaids, security guards and the like.

In 2019, data from the Bank of Uganda indicated that remittances had grown to $1.21b (Shs4.2 trillion), boosted by proceeds from labour exports to the Middle East countries, which over the years have grown to obscure some of the traditional remittance sources.

But during this year’s Labour Day celebrations at State House on May 1, Mr Museveni scolded the practice of labour exportation, claiming his government has what it takes to create 70 million jobs but on condition that his message of commercial agriculture is heeded.

“For me, I don’t believe in labour export. Countries that externalise labour are countries that have missed something. I have proof,” Mr Museveni said.

That be as it is, the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development instituted a Labour externalisation policy in 2015, moved in a bid to regularise the movement of labour that has seen the movement of more than 70,000 Ugandans to the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Bahrain, Oman, Iraq, Qatar and Afghanistan.

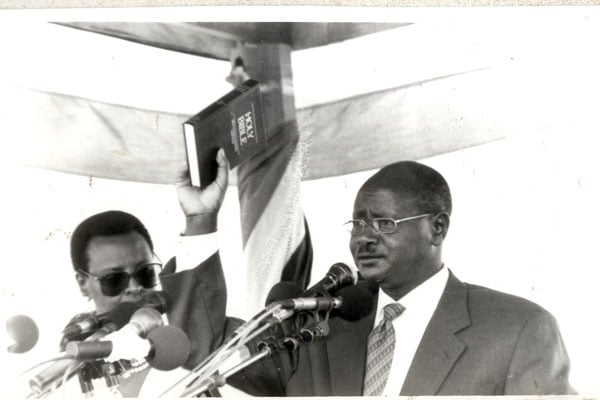

President Museveni. PHOTO/FILE

The President added: “I have never seen South Koreans exporting labour. The only South Korean I have seen (exported) is (former United Nations secretary-general) Ban Ki-moon. Their country is half the size of Uganda but you don’t see them (exported). I am now for the South Korean approach.”

Mr Museveni, as a solution, flew into the future. “We are going to create the jobs; the problem is the reluctance to take our advice, which has worked (elsewhere). The jobs are there but they will only come in big numbers if we listen to NRM’s principle of social-economic transformation,” Mr Museveni, who has been in power since January 1986, said.

“Let us take it that seven million homesteads have access to at least an acre [of land] because even calculative agriculture can blossom on an acre. I have proof from a man called Nyakana in Fort Portal, who is doing wonders on an acre.

Problems come when you have no kibalo [mathematics],” the President said, adding: “So if these can be supported to do commercial agriculture and employ at least 10 people each either directly or indirectly, that would be 70 million jobs. We would have jobs here to even give other people [foreigners] some. Here in central [Uganda], most of the people who run around as Baganda, are Banyarwanda who came because there were jobs here with no one to do them locally during the colonial times because Uganda is so rich.”

Cost of labour

As the kisanja hakuna mchezo term is ending, Mr Museveni still believes having cheap labour will attract investors to Uganda and lead to an industrialisation boom.

“When labour costs in China started going up, factories started coming here. Before coronavirus, factories were running out of China because salaries in China has now gone up. I am ready to discuss the issue of minimum wage. Let us study this matter seriously,” Mr Museveni said during the Labour Day function, in response to an impassioned plea by Workers MP Sam Lyomoki for the government to address the issue of Ugandan workers being paid more as a strategy for economic emancipation.

Mr Museveni then gave a dizzying blow to a higher minimum wage crusaders: “In the last 43 years since China opened up, it was able to attract a lot of investment because of lower labour costs. There’s no doubt that if you address the issue of minimum wage carelessly, that’s how industries leave.”

With three days left to another swearing-in – for a term that gives him the chance to be in charge of Uganda for two generations – Mr Museveni appears to speak with a sense of urgency about the things his government has promised for many years but has not done.

The rules for the suppression of Covid-19 that his own government set are to be violated – with the government saying more than 4,000 guests are expected, way higher than the 200 maximum limit set for public gatherings during this period – because of the import of the occasion. And when Mr Museveni finally takes the Bible to take the oaths on May 12, he will likely feel the weight of duty that he has to discharge into his 80s.

Other challenges

Cost of power

Another issue that Mr Museveni’s kisanja hakuna mchezo has not solved is the cost of power, which might inhibit the so-called industrialisation process of the NRM government. In 2005, Mr Museveni’s government signed a 20-year concession with Umeme, a power distribution company, but the company has come under fire from the public for hiking power tariffs and charges, which users say are unexplained.

The President has previously threatened to terminate the concession for Umeme, only to walk back on that threat, saying Umeme might sue.

With the concession ending in four years’ time, earlier this year, Ms Goretti Kitutu, the Minister of Energy and Mineral Development, intimated that the government is in talks with Umeme to see that the contract is renewed, and that Mr Museveni was taking the lead.

“These negotiations are going on at the high level of His Excellency and we will get you informed when an agreement is reached,” the minister said.

But during the Labour Day event, Mr Museveni said he had no idea how Umeme got the 20-year concession in the first place.

“Government officials went behind my back to sign a very expensive deal for construction of Bujagali hydropower plant, as well as the 2005 concession that allowed Umeme- a private company- to take over power distribution from Uganda Electricity Distribution Company Limited [UEDCL],” Mr Museveni said.

He added: “I need you to listen to this and take notes, for industrial parks, the power will go straight from generation to the industrial parks, not through Umeme. If Umeme collapses, my mother died and I buried her. Mzee Kaguta died… people die and societies move on.”

The President repeated the vow on directly supplying power to industrial parks when he visited select factories at Namanve during the week, seeming to emit new energy and looking the country in the eye to make yet another promise to transform Uganda.