Prime

A coup in Uganda? Prepare for a long wait

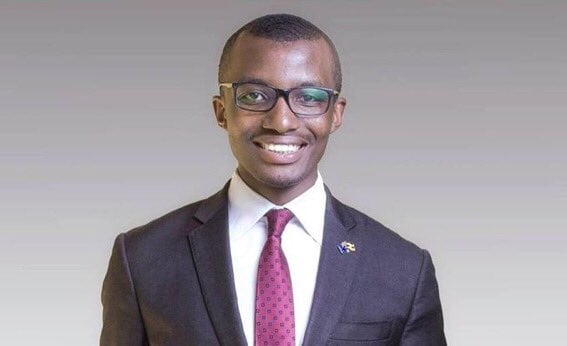

Mr Charles Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”.

What you need to know:

It takes from about one-and-a-half to two generations (40 to 50 years) for the dynamics to change...

The August 30 coup, in Gabon, which ousted President Ali Bongo, was the seventh successful one in Africa in the last three years. Happening in Central Africa, it was the first to take place outside the Western Africa-Sahel “coup belt” of Guinea, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Chad, and Sudan, and led to panicked speculation about “spread” and “increasing contagion.”

As Ugandans who have lost faith in ever having a political order that’s not violent and corrupt are won’t to do, they upped their arguments (and wish) that a coup was closer at hand in a country President Yoweri Museveni has ruled with a firm hand - which lately has visibly trembled on the sceptre - for nearly 40 years, and where a potentially chaotic transition has begun to unfold.

Along with this, there have been discussions whether the coups in West Africa-Sahel mark the end of the Western imperialist dominion over Africa, and a triumph of the East – Russia, China.

It is slippery business forecasting what will happen in politics, let alone the African variety. However, those expecting a coup in Uganda might have to wait a bit longer.

Some of the reasons why we are unlikely to have a coup in Uganda soon are the very same ones that account for some of the failures of the Museveni government over the last 37 years.

You see, after the 1960s independence decade in Africa, the 1970s onward were marked by a very different kind of freedom movement. We had mass liberation wars against European colonialism mostly in the Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique, against settler British colonials in Zimbabwe, and Namibia (which was partly ruled by apartheid South Africa), all in Southern African Africa. The scale of national mass mobilisation was much bigger than in previous anti-colonial wars (e.g. Mau Mau in Kenya, and Maji Maji rebellion in Tanganyika), but the biggest distinction was how global they were. They drew in an alliance of African and European (e.g. Soviet Union), Asian (China, India, Indonesia), and Caribbean (Cuba) socialist allies, and internationalist civil society movements. The incumbent regimes, likewise, were able to bring on board wider backing too, often including the USA that was never a colonial power in Africa.

The scale of these operations, the ingenuity it required of the rebel leaders, and the heavy toll they took on the people, in victory produced a calibre of African leaders with the political organisational skills we had seen very little of before, and also a people so traumatised by the violence, they were extremely reluctant to go back to it again. They also gave us Africa’s first cohort of politico-military parties, like the National Resistance Movement (NRM), the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF), Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) and so forth. The leaders of these parties, like President Yoweri Museveni, the late Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, Sam Nujoma in Namibia, et al, had been both leaders of the military wings of their liberation movements, and political wings too. They were hybrids.

Once they won the war and became presidents, they had varying levels of success in separating the military from the political. Namibia has done so considerably. In Uganda, Mozambique, Angola, Zimbabwe, the ruling parties remained closely fused to the military. Therefore under Museveni, civilian rule has been nominal. Real power remained with the military.

This fusion of ruling party, state, and army has been a source of both weakness, but also strength for Museveni’s government and others. It constrained the imagination on political and economic policy, and made politics violent and repressive in ways that have sapped the country’s creative energies. But it was also a source of stability in a long-troubled country.

The above reasons is why we argue that this weakness, reduces coup risk. In the two mainland Africa Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique where the bulk of the fighting took place (other countries like Cape Verde gained independence because Portugal was defeated in Angola and Mozambique), there has never been a successful coup. The only mainland African country where a major liberation war was centred and is ruled by a politico-military party where there was a coup was Zimbabwe in 2017, when an ailing, stark raving mad Mugabe was ousted, and his deputy, Emmerson Mnangagwa, succeeded him. But that was more of a domestic brother vs. brother quarrel, than coup. Zanu-PF remained intact in power.

Together, these things suggest that it takes from about one-and-a-half to two generations (40 to 50 years) for the dynamics to change, and the necessary loss of historical memory needed for a military coup to happen in politico-military party-ruled states. Uganda, then, could truly enter the danger zone in 2026.

Mr Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”.

Twitter@cobbo3