Prime

The art of paying science teachers more is at the heart of poor policy

Daniel K. Kalinaki

What you need to know:

- ‘Creating a love for science must involve creating an ecosystem in which learners are attracted to the subjects at an early age, and given the tools to tinker, and then pathways created to recognise achievement and reward innovation, including among teachers.

I remember Mr Fred Wabwire’s eyes. Not his explanation of Archimedes’ Principle, or none of that stuff about why an object will remain at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless compelled to change its state by the action of an external force. Yawn. It is his eyes I remember.

Which is surprising to the point of being disappointing, for they were remarkable for being unremarkable. It could have been because, for a spare-bodied man, they popped out of their sockets, as if the force pushing them outwards was winning the constant battle against the opposite reaction.

Perhaps it was because my own eyes, glazing over from a combination of heavy starch lunches and deviously humid afternoon heat, needed something to focus on to keep my head from obeying the law of gravity and plonking down on the desk.

If he noticed the blank face Mr Wabwire was polite enough not to say anything about it. He probably understood that while I, and many of my classmates, could see his lips moving, we could barely make out a word of what he was saying. The laws of physics left his mouth, vibrated through the afternoon humidity and were translated into sound in our ears. Once there, however, the sound interacted with our dulled brains and each applied forces that were of equal magnitude and opposite direction.

He spoke, we heard. There was no understanding. The match always ended Physics 1, Posho 1. The next term I obtained an expensive copy of the textbook Mr Wabwire used: Physics, by A. F. Abbott. It had that nice new-book smell and the pages were crisp and full of interesting diagrams. But it was all Greek. Physics 1, Posho 1.

When it became clear that the subject was compulsory and examinable at O-level, self-preservation and the fear of failure did just enough to push me to pass physics much better than I had feared.

I have no idea what Mr Wabwire or any of the other teachers at Busoga College Mwiri were paid – and the thread count of their shirts, as one measure, wasn’t very reassuring. But I can tell you for free that no amount of money thrown at Mr Wabwire could have turned me into a nuclear physicist. I just wasn’t interested.

Neither was I in Biology with its mitochondria, or Mathematics which triggered palpitations and a constant urge to go and do susu, especially when the teacher started picking on students to answer questions.

Chemistry, on the other hand, offered more promise, especially in the lab. The test tubes, with their pungent smells were infinitely more interesting, even when everyone’s sample turned pink while mine was a forest green. I was even briefly an A student until I lost interest and stopped caring about Bunsen’s burners – around the same time I discovered the great profit to be made from supplying those students who lit fires at the end of tobacco sticks.

Teachers need to be paid better. But paying science teachers higher to encourage the production of more scientists is neither smart nor scientific. As we have seen, it creates a moral hazard where the Arts teachers feel discriminated against and lose morale, or just stop turning up. In reality science teachers, like their arts counterparts, only pass down textbook information and do not create any knowledge themselves.

Creating a love for science must involve creating an ecosystem in which learners are attracted to the subjects at an early age, and given the tools to tinker, and then pathways created to recognise achievement and reward innovation, including among teachers.

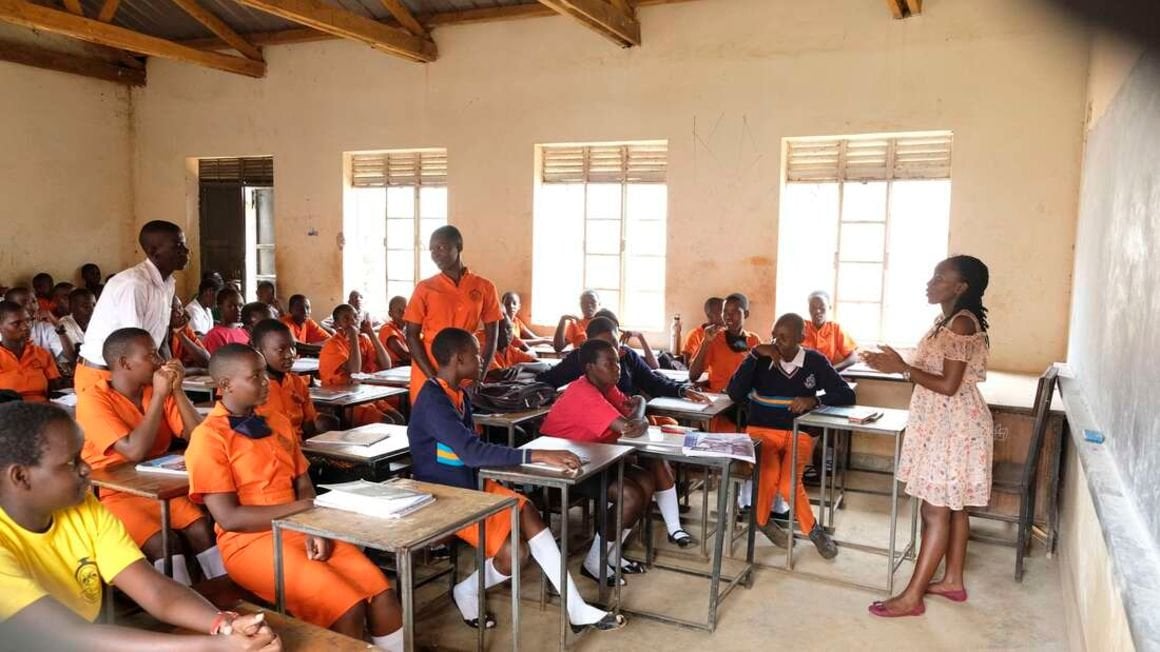

Encouraging more kids to study the sciences need not be at the expense of the arts. It is not a zero-sum equation and the world needs both. Our challenge isn’t too many students doing the arts and not enough doing sciences; it is that we don’t keep kids in school long enough, and those that do have very low learning outcomes, across disciplines.

We are trying to solve our problems with the same levels of intelligence – to use the word loosely – that contributed to them in the first place. Improving learner outcomes requires broader investment in education, and building a national culture of innovation, execution and excellence.

Mr Kalinaki is a journalist and poor man’s freedom fighter.

[email protected]; @Kalinaki