We thought bribes were better than bullets for ballots, what happened?

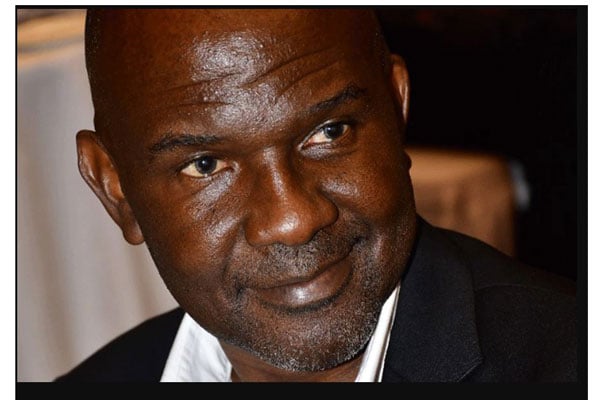

Mr Daniel Kalinaki is a journalist and poor man’s freedom fighter. [email protected] | @Kalinaki

What you need to know:

Why the violence when there is a lot for the incumbent to campaign on as a ‘developmental’ leader.

After the violence of the 2001 and 2006 elections, many were pleasantly surprised by the mild, even boring, nature of 2011 and 2016. We believed, then, that the end of military operations against the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda had removed the excuse of the army’s inevitable role in the political arena, particularly during elections.

Without the leakage of war expenditure, the government, we assumed, now had financial legroom to invest in creating a peace dividend from which it could extract electoral support. In fact, this column argued that while bribery is morally wrong, it is better than bullets when used to procure political support and represents progress.

How, then, do we explain that we have registered more deaths in just a month of campaigning than we did in the last four elections? A few random thoughts, beginning in Gulu, in August 1986: An attack by remnants of the defeated UNLA startled the NRA soldiers in the area, prompting them to commit what many believe were the first extra-judicial killings by the new government. Five soldiers questioned a market trader, then ordered him to squat, and shot him in the head.

Moments later, Charles Ojara, 15 years old, emerged out of his house with his sister and ran into the soldiers. His sister turned and ran back into the house. Charles froze, and was then shot in the chest and killed. He was just a kid.

A Catholic priest witnessed the incident and took it up with the Army Commander, who apologised. The NRA had assiduously created and defended the image of a disciplined force and this behaviour was unbecoming, the army commander pointed out.

In the aftermath of the recent shooting dead of more than 50 Ugandans when protests broke out following the arrest of presidential candidate Robert Kyagulanyi, the Security minister refused to apologise. He instead warned that the security forces are capable of even more violence against those considered to be breaking the law.

The decades after 1986 put the NRA’s human rights credentials to the test, in northern Uganda, at Mukura, and elsewhere, but it also allowed for the evolution into the UPDF as a more national army, and the recruitment of many career soldiers into the force, many of whom are highly-trained and respected professionals.

That the person who as army commander apologised in 1986 is the same person who refused to do so as Security minister in 2020 says a bit about “stability, continuity and change” ethos in the top leadership of the armed forces. But it does not tell us what younger officers would have said had they been the ones cast in the spotlight.

It is telling that on this occasion, and on previous ones where he has been sufficiently irked, the commander-in-chief referred to the armed forces as ‘NRA’, not UPDF. Names have meaning.

The unprecedented violence in this campaign also suggests that the hawks in the regime see a bigger threat in the demographics than they publicly let on. In a country with a median age of just 16, we have always expected the youth vote to be key. The reaction from security suggests that many youthful voters are ready to swing or vote along with their peers, which could create a snowball effect.

To that end the violence is a logical vote-suppressing tool to break up momentum during the campaigns and keep voter turn-out low among youthful voters on Election Day. This is a stalling manoeuvre, but one that does not resolve the problem.

Which brings us to the common-sense question: Why the violence when there is a lot for the incumbent to campaign on as a ‘developmental’ leader - power dams, roads, oil investments just around the corner? Here we can explore two related hypotheses. The first is that the incumbent doesn’t have the time to make trickle-down arguments and considers it more pragmatic to win at all costs, then stitch the wounds after.

The second is that all this ‘development’ has actually not trickled down as much as it should. This is a transmission problem, in the form of a disconnect between objectives and outcomes.

As we will argue next week, the strength of incumbency is its worst handicap as rent-seeking sucks up the surplus. Bribes are better than bullets, but only if they aren’t stolen in transit!

Mr Kalinaki is a journalist and poor man’s freedom fighter.

[email protected] @Kalinaki