Anonymous city-zen doers of good

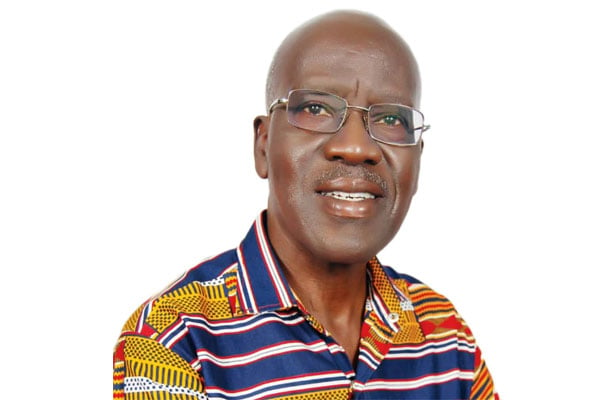

Prof Timothy Wangusa

What you need to know:

‘‘They hated cities with a passion and extolled the simple lifestyles of rural populations”

Since the inhabitants of a country are generally known as ‘citizens’, let us give the name ‘city-zens’ to the inhabitants of a city. And having agreed on that, let us propose that whereas the inhabitants of a countryside community tend to know one another, the inhabitants of a city generally do not know one another. Let us further propose that not knowing one another has amazing potential for being a really good thing!

And that is it! That not knowing one another can be practically a very good thing. Indeed this is the very claim made by one high-ranking and deservingly acclaimed book of mid-20th Century, and by one graphic and unforgettable story or parable among the many such stories that one encounters in ‘The Book of Books’. The high-ranking book of mid-20th Century is The Secular City by Harvey Cox, a Harvard University emeritus professor of Theology (b. 1929 – now aged 93); and the graphic and unforgettable story is the very well-known one which opens with a traveller on his way from one city to the next, and somewhere in between being attacked, robbed and savaged by armed thugs, leaving him for dead.

In my personal experience, Cox’s The Secular City (1965) ranks among the top five eye-opening books that I have ever had the privilege of reading. Becoming an instant international bestseller upon publication, that very year (1965) it also found its way to a Makerere University lecture room, where my course-mates and I were in the second half of our first year of Religious Studies (in combination with two other subjects). The book’s central message is simply an intellectual and spiritual stunner.

And that central message is that the secular phenomenon that the ‘city of man’ happens to be is part of God’s existential purpose for humanity. That the city provides a huge and complex context in which individual human beings – eschewing the language of mere piety without good works – should seek to do good to fellow city-dwellers with no regard to whether we know one another or not. In a nutshell, Cox’s vision is that the city provides us with the opportunity to anonymously do good to fellow humans.

Wow, I said to myself! Here was a surprising and refreshing view of the city. It was the very opposite of another view, or rather sentiment, that I was soon to increasingly imbibe in a different academic pursuit, namely, Literary Studies – the hatred of cities in the writings of the British school of writers known as Romantic poets, pre-eminent from the 1790s to the 1830s. They hated cities with a passion and extolled the simple lifestyles of rural populations where everyone knew his/her neighbours by name.

Back to the story in ‘The Book of Books’ about the traveller between two cities who fell among deadly thugs, its essence is in consonance with Cox’s view of anonymous doers of good to and agents of compassion for equally anonymous populations in need of one form of support or another.

That story begins with a legal expert wanting to be told by the Teacher what he can do to inherit life that will never end. In answer, he is told to keep all the commandments, which he summarises for himself as: loving God with one’s entire being – and loving one’s neighbour as much as one loves one’s own self. ‘And who is my neighbour?’ he self-importantly asks, cocksure that it must be the well-known person next door. Then follows the heart of the story, in which a real neighbour is re-defined as the person of no known name and address that does good to or for someone of no known name and address.

And such, to us all, is the challenging invitation of the modern secular city, with all its horrible negatives – to become anonymous doers of good to anonymous neighbours.

Prof Wangusa is a poet and novelist. [email protected]