Prime

Our burials say we are stronger together yet our problems don’t

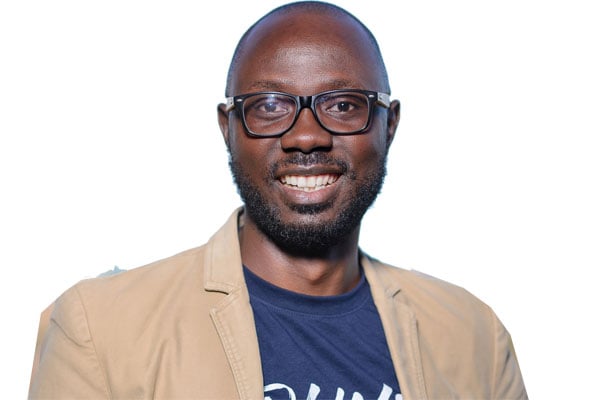

Raymond Mujuni

What you need to know:

It hasn’t been studied yet, but the social engineering and organization that delivers effectively at African burials is something

When people pass on, in this neck of the woods, saucepans are quickly gathered in the home, a coffin – and money for it - is quickly put together and word travels round and fast on vigil and burial dates.

It hasn’t been studied yet, but the social engineering and organization that delivers effectively at African burials is something. From the point of death, it takes the average Ugandan family three to four days to put the body in the ground [One if you’re of Islamic faith].

Burials test the strength of community and the mark the important role that community plays in the development of individuals. Burials also open up homes to communal scrutiny as the mourners have to walk inside the house to get to their convenience matters sorted.

Families’ reputations are also adjudged at funerals; will the area LC1 chairman come? Will they make a speech? What will they say? Will the local church give it’s choir to sing for free? Will the benches of the church be put to the disposal of the family to fill up the tent? What will the village drunkard shout from the back of the tent?

You needn’t lay cover in the dark at the village SACCO to determine who the richest person on the village is; on the front pews of each burial, there will be the richest and powerful from the village. In nationally prominent funerals, they might take a second or third bench but they’ll be there. You might also want to have a keen look at who the burial committee walks to when they hit a snag.

Because of the unexpected nature and short periods families have to bury their loved ones – and the ugly breadth of grief - burials remain largely unscripted and remind us all of why it is important to belong to a community and do right by it.

Burial grounds also speak, not just of how many people families have lost but at the strength of organization in the family. Uganda is one of the few countries where more than four generations can be found buried in a backyard. With an average life expectancy of 68 years, that’s nearly three centuries of history. Each grave is a firm repository of a story, a life lived, a raison d’etre for the family, a feeling of Ubuntu and what the South Africans call ‘As’phelelanga’ [We are not complete without our ancestors]

I am fleshing out this column, not to premonition anyone but to remind us of the role of community – and mostly in the preparation of the final journey of life. Community is undeniably the strongest link for societies. And to also remind everyone of agency. At burials, we scarcely ask whether the budget for rice or porridge has been approved, we show up and work with what is there – and often contribute to making the final journey a success.

The agency at our burials should breathe into our public affairs. The roads are dead, yes, but will you be the village drunkard shouting about them from the back of the tent or the mason laying bricks and doing something about them?

Our burials also tell us we are capable of solving complex problems if we work together and across the aisle. They tell us of the strong empathy required to do the work – and the inconsequential nature of our divisions during death.

Our sense of community and society is dying and perhaps now’s the time to come to this funeral with some eulogies and answers; only then can we create the after life and next generation we desire.