Prime

From across the table: why are we the miyaayu?

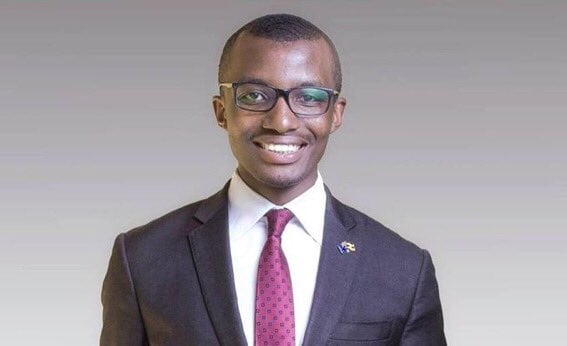

Raymond Mujuni

What you need to know:

If you want to fully understand Uganda, forget what you’ve read in the papers or what you’ve heard from tour operators, the country is well enmeshed and explained in the songs that Ugandans choose to listen to

I probably shouldn’t be saying this but I am in a bar, in Masaka – and truly, the only bars closed, as a twitter user noted recently, are bars of soap.

The music is loud, the people even more. I can see from the corner of my eye a man in his mid-30’s dancing with a bottle on his head and from the other corner, a situation that’s about to explode. There’s an MC on the microphone shouting ‘Masaka Ku Ntiko’ every 10 minutes.

There’s still Covid19 and in its new form, the omicron variant.

The logical question to ask is why aren’t we afraid?

If not of the new omicron variant of Covid-19, why aren’t we afraid of the government declared curfew and permanent closure of bars that has lasted almost two years?

The answer is simple; ‘We are the miyaayu’!

If you want to fully understand Uganda, forget what you’ve read in the papers or what you’ve heard from tour operators, the country is well enmeshed and explained in the songs that Ugandans choose to listen to.

At the start of the COVID19 pandemic, a young man famed as Mudra D’ Viral released a hit song titled ‘Muyaayu’. It went far and wide. It was received in ‘closed bars’, on house living rooms, at market stalls and dare I say on some pulpits.

The word ‘Muyaayu’ itself betrayed the good mannered way we like to look at ourselves. Muyaayu is a Luganda word for ‘stray cat’. It is also a round descriptive word for the mannerisms that stray cats come with; recklessness, indifference, off-the-edge adventure and most importantly, unruliness.

Muyayu, as a song, did well with Ugandan audiences because, for once, here was a song that was saying out loud what we all liked to whisper in ears of our neighbours; that married men were spending hefty amounts of money in hotels, that people were conspiring every day to rob the system through fake patronage, that a lot of relationships revolved around love – oh wait, not that – money!

This stray cat behavior for many Ugandans is a combined result of years of misrule and general societal breakdown – not specific to Uganda alone.

Something about society has given way that is so irretrievable. It’s inexplicable in any real terms but it is a fundamental part of the social contract. In this household of Uganda, many Ugandans are the stray cat, often returning to steal the milk set aside for the house cats yet not enduring the hard days’ work.

The stray cats have learnt there exists better fortune living on the edge and outside of the fence that it has become inconvincible to settle for the home. The stray cat behaviour manifests on our roads, where, when the traffic holds up for even a giffy, theres no business playing by the rules, we create a second lane or tag at the tail of a convoy – and aren’t those far too many?

It also manifests in the political leadership who, upon seeing the works of their hands in creating the state, realise it is far too dysfunctional that they take their children to schools outside the country, buy apartments in better organized countries and spend a fortune creating a luxury in-house to avoid any real cost.

The problem with the stray cat is that one day, its luck runs out – it has eaten from garbage bins that corrode its intestines, made enemies with many cats – most of them domestic, it’s unkempt and unwashed and undesirable amongst the good ones that any contact with the real world will leave it beaten to a pulp or killed instantly.

We are the miyaayu, but the miyaayu die too soon – or live a largely abandoned life – and that’s no way to live!