Novelist who allocated Jesus a sex partner

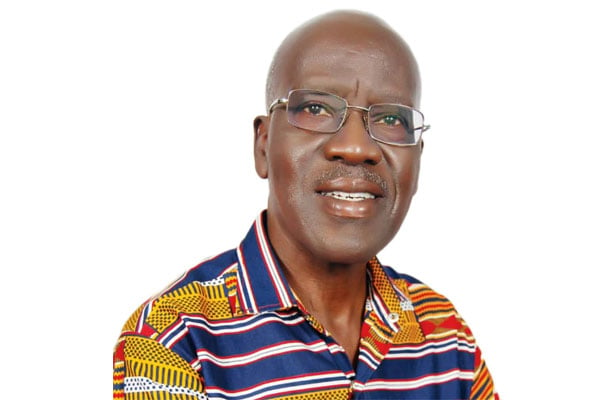

Prof Timothy Wangusa

What you need to know:

- Upon reading the text, my Makerere cohorts sat up inside our intellects and spirits and blinked.

That was our first and most memorable brain teaser – Jesus Christ portrayed as having had a sex partner, after his resurrection! We were First Year students of English at Makerere in 1964, the second full year of Uganda’s honeymoon as an ‘independent’ country with a future of calamities and disasters as yet beyond imagination.

The brain teaser was deliberately and smartly programmed to feature at the very beginning of our Literature course on the Novel and Prose Fiction, presumably to make us sit up and blink right away, the majority of us inevitably coming, as we did, from high schools where the Lord Jesus was revered as having been above human copulation, schools with Roman Catholic and Church Missionary Society (CMS) foundations. And there, for our intellectual and analytical growth, was this apparent assault on our spiritual sensibilities, entitled “The Man who Died” by DH Lawrence.

(Someone alive and awake out there, please tell DHL courier services that they are not the original DHL, and that their predecessor is David Herbert Lawrence [1885-1930]). This is the DHL who makes the resurrected ‘man who died’ excitedly go about trying his luck at everything he missed before his death. After having his first bash at sex, “the man who died” exclaims with his mouth wide open, ‘Father, why did you hide this from me?’

But it was not the first time that we were meeting this really notorious DH Lawrence, nor would it be the last time that we would be meeting him.

At Higher School Certificate (HSC) level, where we were exclusively confined to British literature – as if Amos Tutuola’s pioneer African novel in English, The Palm-wine Drinkard (1952) and Chinua Achebe’s ‘big-bang’ Things Fall Apart (1958) were non-existent – we had been subjected to, among other British texts, DH Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers (1913).

In this novel, as in his other two (in)famous novels – Women in Love (1920) and Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) – Lawrence especially champions ‘sexuality and instinctive vitality’ (in addition to his other principle concerns of modernity together with its evils of industrialisation and attendant social alienation.) His championing of freely expressed sexuality is characterised by his portraits of actors unrestrained by moral and religious norms, such as virginity and chastity.

The boy Paul Morel in Sons and Lovers has uncontrolled sexual flings with an exuberant young divorcee woman; he never begins to sexually warm up to his girl-friend, Miriam, who is religiously intense, and he feels like she wants to squeeze the spirit out of him; and rather than ever contemplate helping to lovingly polish her shoes, he devotedly polished those of his pampering and attractive mother – and there is your ‘Oedipus complex’ for you!

Indeed, DH Lawrence knew and was an avid consumer of the ideas of the Austrian father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), especially his ideas on sub-conscious archetypes and symbols. And hence Paul’s not polishing his girl-friend’s shoes but polishing those of his mother – the shoes being symbolic of female genitalia, so we learn.

Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover was another moral shock. Lord Chatterley (what is sexually important in high social status?) is paralysed from the waist downwards and in a wheel-chair. In his sexual absence, his wife has a romping romantic time with the couple’s shamba-man, which Lawrence describes in unprecedented graphic and lewd details.

This is the DH Lawrence who invents a wife for the previously virgin and chaste imaginary “man who died” and then resurrected. Upon reading the text, my Makerere 1964 Literature cohorts indeed sat up inside our intellects and spirits and blinked. We sat up and asked questions.

For instance, since God created man in His own image, why did He add to man that which He Himself did not have, namely, gender differential and sexual consummation? Or does He perhaps – like the classical Greek and Roman gods with their wives – does He, might He perhaps…?

Prof Timothy Wangusa is a poet and novelist.