Prime

The real timber of business coffins in Uganda is loan interest rates

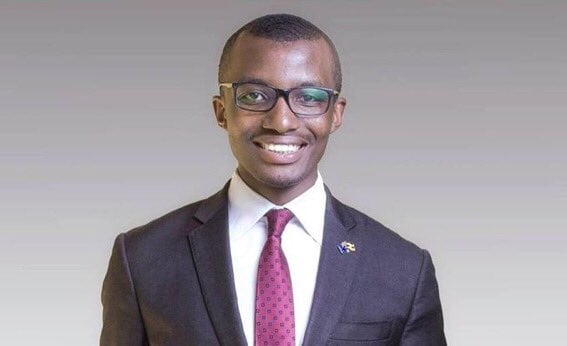

Raymond Mujuni

In the early days of 2016, an incontrovertible source sent to my news desk a brown envelope marked with the words; “Your country needs you”.

I was a desk editor then with NTV. We had come off a tacky election in which both the winning candidate announced by the Electoral Commission and the opposition candidate had sworn themselves in – each was running their own government. The political waters were muddied and so polarized, it was hard for this envelope to find space in Parliament and be debated on it’s merits.

In the envelope the incontrovertible source had sent was; a list of companies, the liability they owed to banks, the assets at stake, number of employees in each entity and the tax contribution of each of 65 companies on the list.

I quickly read through it and locked my then news manager into his office and told him we had a major story on our hands. The simple story was that 65 companies were looking for a Shs 1.3 trillion bail out from the government. They jointly had properties worth Shs 1.4 trillion that banks were going to take and they jointly paid taxes worth Shs 70 billion annually.

The harder story was that a lot of the most successful Ugandan entities were drowning in debt, partly due to non-payment by the government for services they had rendered and the other part due to high interest rates in the debt market.

The knock-on effect of this leak, my source would later tell me, was that either those companies get foreclosed on or, as fate later had it, the banks in which they held their debts would collapse under the weight of non-performing loans.

Whatever direction this took, my source insisted, should not involve tax payers’ money as a bailout or depositor’s money in the banks.

My news manager insisted we first get the facts right and so the most important task at hand was verifying the authenticity of the claims the list made. My source was incontrovertible but the nature of the news is such that verifying facts is more sacrosanct.

We established the facts and broke the story first at 9pm and in the morning this publication ran it too.

It was such an important story. You could tell, first, by the number of calls that we got after it was published and the number of legal threats that followed. But it was also so important that it had lasting impact. It was the kind of story that would live with us.

That story reared its ugly head again last week as vantage capital and Simba group locked horns again. Simba group was on that list in 2016, it owed money, then to Crane Bank which has since sunk. This paper reported that the money Simba group owes Vantage Capital was partly used to pay the Crane Bank loan, the loan that was in the bail out list.

Some 22 companies on that list of 65 have since folded and sold their franchises. It is no longer enough to say that the companies borrowed beyond their means, neither is it enough to say that they need to be bailed out. A lot more SME’s have folded under the yoke of bank loans.

There’s a case to be made for the fact that the average return on capital in Uganda is declining so rapidly, from 22 per cent in 2006 to a mere 3.7 per cent in 2020. With that return, a bank loan at the interest of 18 to 22 per cent is not really supporting business; it is the real timber in which business coffins are made.

On another day, in this column, we shall debate the demerits of urging production whilst ignoring consumption, but today, lets end at that, what truly is debt if the economic environment isn’t designed for success?

My incontrovertible source texted me last week to say; Simba group is not to be laughed at or mocked, he is to be understood as a case study.