Prime

Uganda’s common good is shattering at the seams

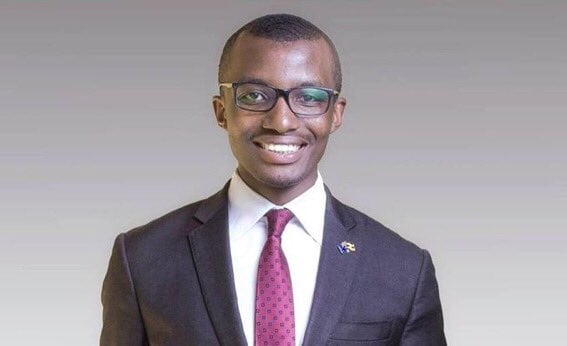

Raymond Mujuni

What you need to know:

- There is a sentiment – maybe fact – that Uganda works for some people and neglects others. In my generation for example, a lot of young people believe the economy of Uganda works for the wealthy and elites and gives them an edge.

Of seemingly complex national problems, we must start by asking simple, coherent and concise questions.

The one I seek to ask today is what, in Uganda, is the common good?

Shortly after the completion of the 2011 Presidential election, Kadongo Kamu singer Matthias Walukaga went into the studios to produce the famed hit song ‘Bakowu’. In it, he captured the national psyche of tiredness. He chronicled the corrosive failures of government and governance, he spoke with candor of the declining social and moral values, he attacked the money lending community for their pervasive traits, as did he go after the plagiarists for pilfering the creative genius of a few.

He would have spared adulterers if the song had cut to the regular time of three minutes but for nine minutes! Why not go after the religious leaders and incompetent teachers!

He warned, shortly after, that without a quick restoration of some form of common good, pandemonium would ensue – and it has ensued, in small, unspeakable ways. Shootings, murders, mob violence etc…

For those that mill at the mouths over Kadongo Kamu, you can find the same reference in the writing of David Mpanga, who said; “We shall never see the Uganda we want until we develop a central nervous system that enables us feel each other’s pain.”

He said this, first, after the murder of Kenneth Akena by Matthew Kanyamunyu and repeated it at the 30-year anniversary of the Monitor, a few weeks ago.

Uganda’s common good seems to elude cross sections of the population.

In political science, common good takes on two forms; the procedural and the substantive. In the procedural one, common good is arrived at through collective participation; this would take the form of a constitution or national elections but both have been fundamentally altered to be believable.

The substantive common good on the other hand is one that is shared by and beneficial to all; this would take the form of taxes, social welfare, education, health et al.

There is a sentiment – maybe fact – that Uganda works for some people and neglects others. In my generation for example, a lot of young people believe the economy of Uganda works for the wealthy and elites and gives them an edge. There is also a tribal (better said as regional) sentiment to this – that the economy works for those from the West, which, of course is sentiment too but can be, with a reading of facts skewed as true. In the West, there is a sentiment that power is in hands of a minority few.

At each turn, this power, this common interest in the governance of and benefit from Uganda is contested. We are lucky, in most of these times, the contest is civil but increasingly the contests are bare knuckle, double footed and cold-knife-on-neck.

Simply put, ‘Abantu bakoowu’ [People are tired].