Prime

Go slow on DNA on IDs

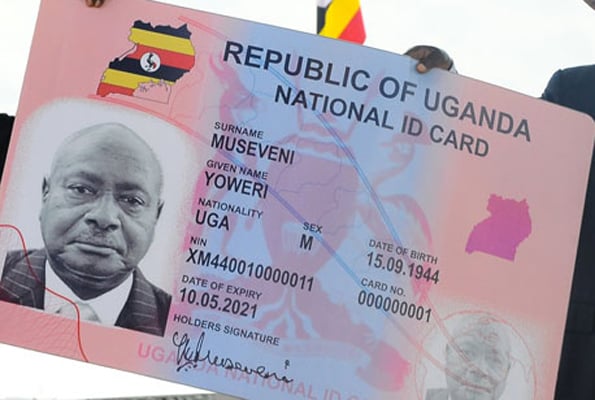

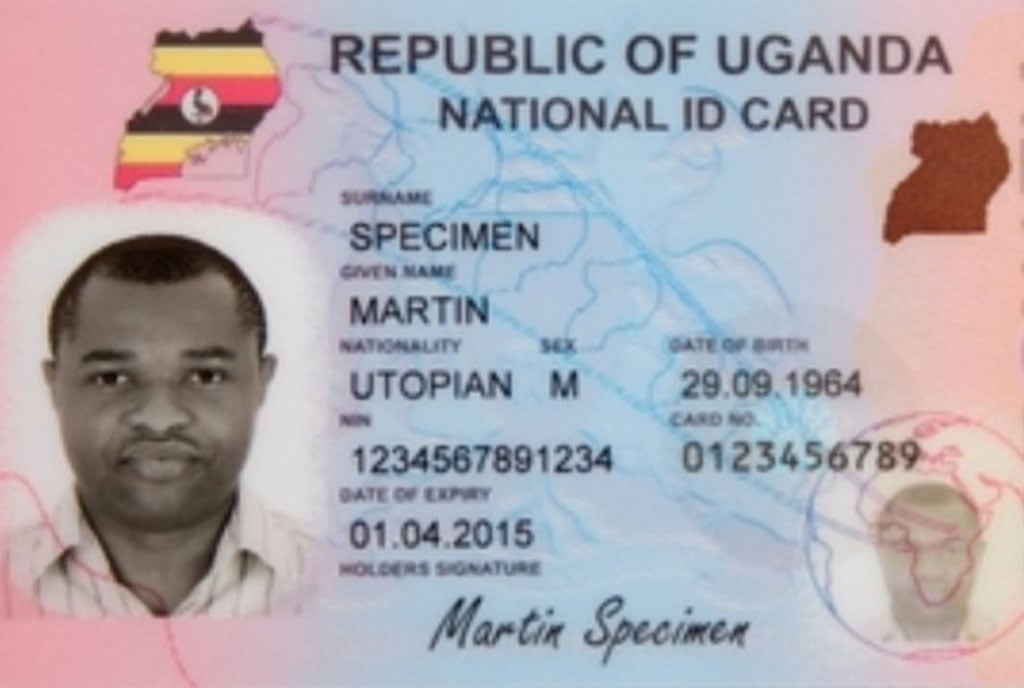

A specimen of the current National ID. The first batch of the IDs, which was issued in 2014, expires in 2024. Photo/FILE

What you need to know:

- The issue: Data collection

- Our view: Instead of looking for DNA, which sounds a herculean task alone, why doesn’t the government corroborate the information within its reach first?

- Even where the State undertakes to guarantee security of personal data, DNA samples shouldn’t be one of the data accessed by anyone other than an individual.

This publication reported in yesterday’s edition that the government now plans to harvest DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid) samples of Ugandans and issue new national identity (ID) cards with the genetic information.

DNA is the molecule inside cells that contains the genetic information responsible for the development and function of an organism and can be passed from one generation to the other.

The revelation made by the State Minister for Internal Affairs, Gen David Muhoozi is disturbing in many ways. Importantly, it is not yet clear how the government intends to acquire the otherwise intrusive information.

Many conversations globally over the last decade have been centred on how private data in the face of rising technology can be protected. Social networking sites such as Facebook have been under scrutiny for leaking users’ data to third parties.

The move to harvest DNA samples, therefore, raises more questions than answers. Why now? Does the data the government has been collecting on a regular basis on multiple platforms not suffice?

ALSO READ: Govt to change national ID cards

The government has data for all national ID holders. It has data for all passport holders. The government has information from voters’ registers, learning institutions, village chairpersons and so on; and most of it is documented.

Yet, somehow, the same government suffers information deficits in times of crime and tracing important documentation or persons of interest.

Most importantly, why does the government want people’s DNA details? To help them in what ways? Aren’t the fingerprints and other details enough?

Instead of looking for DNA, which sounds a herculean task alone, why doesn’t the government corroborate the information within its reach first?

This also raises a rather intriguing matter. Why would one with a national ID be required to apply for a passport or any other government document afresh? Do we have serious data collection and storage mechanisms?

The government has demonstrated that it cannot capture citizens’ data accurately. One example is the national IDs that nearly a quarter of the holders have either spelling errors in names, wrong birth dates or areas of residence.

Why would the government now want Ugandans to trust it with DNA samples? Section 7 of the Data Protection and Privacy Act, 2019 says the government has the power to collect citizens’ data if necessary for the proper performance of a public duty by a public body, national security, or medical purposes.

But Article 27 of the Constitution also provides for citizens’ right to privacy and the law must seek to uphold this tenet.