Respect our teachers

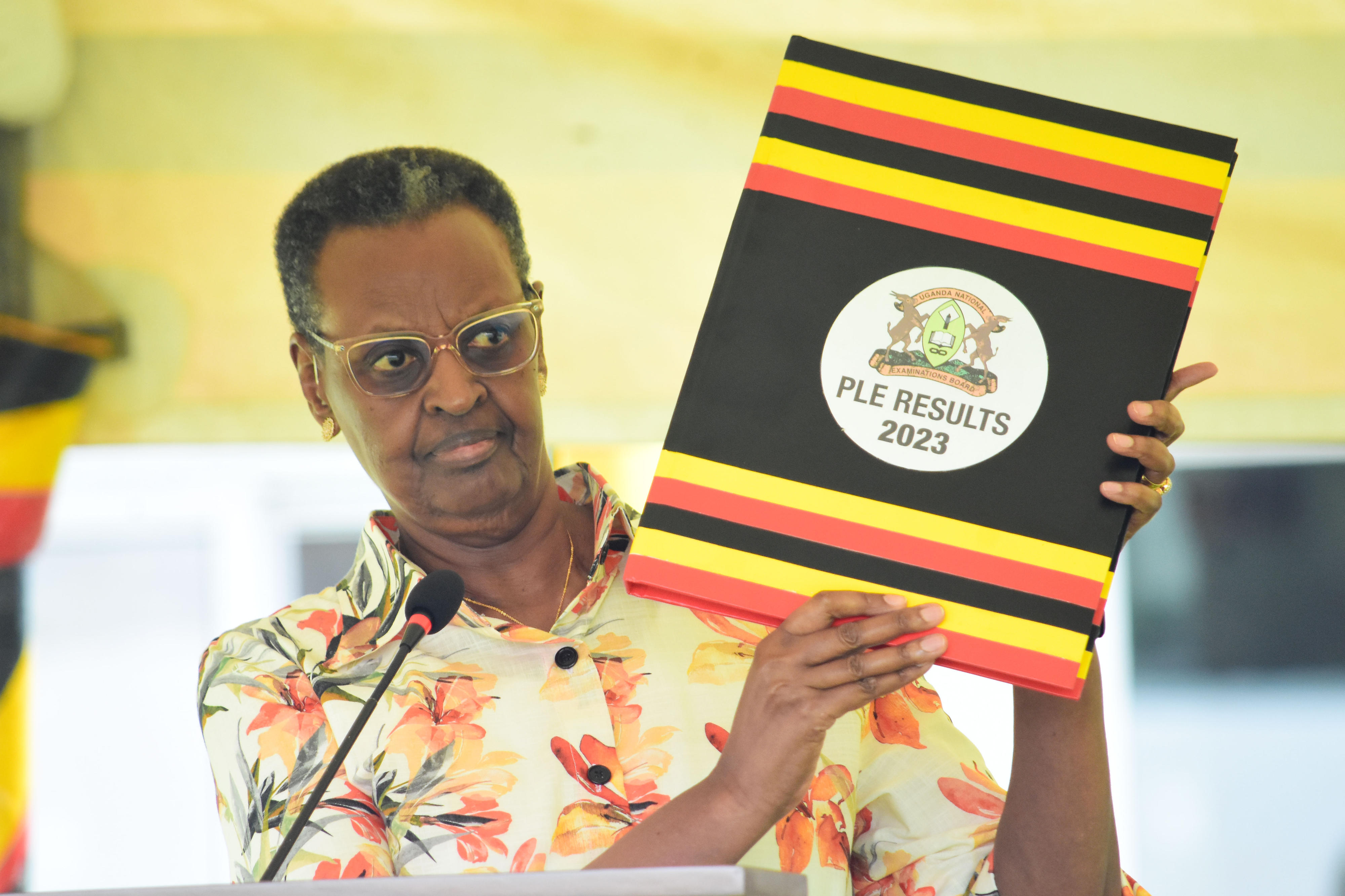

A section of Nakaseke teachers sit the competence exam after their respective schools performed poorly in the 2023 PLE. PHOTO | DAN WANDERA

What you need to know:

First and foremost, there is no evidence to show that knowledge of a subject necessarily determines the ability of a teacher to teach better

Last week, the country was taken aghast by yet another act of humiliation to the teaching profession. The Nakaseke district council after the release of the Primary Leaving Examinations results that showed poor performance in many government aided schools passed a resolution that was implemented by the District Chairperson Mr.Ignatius Koomu to hold competency exams for teachers in select primary schools to prove their level of knowledge of subject content.

These teachers were reportedly ‘tricked’ to come for a meeting at Nakaseke Technical Institute, only for them to be made to sit the exam! The same district in 2017 for the same reasons made Head teachers for ‘underperforming schools’ sit exams and demoted some Head teachers to deputy head teachers and classroom teachers because their schools had performed poorly in Primary Leaving Examinations. How sad!

First and foremost, there is no evidence to show that knowledge of a subject necessarily determines the ability of a teacher to teach better. Teaching is more than just content mastery. It is how a teacher relates with a learner, how a teacher delivers content (pedagogy), how a teacher assesses learning during and after a lesson (formative and summative assessment). The best way to deliver the point home is to say that the best football players are not necessarily the best football coaches. To improve the learning outcomes for local governments especially in the rural areas, I would propose the following areas to be thought through:

a) Teacher and head teacher motivation: This includes doing a thorough analysis specifically on the motivation levels of head teachers and teachers. Having a teacher in the school or even classroom doesn’t necessarily mean they are teaching, and even worse, may not necessarily translate to children learning. What is the capacity of the teachers and head teachers’ autonomy, mastery and purpose to innovate and ensure learning is happening in the lesson, not just delivering content? Does the teacher have the autonomy to change the lesson delivery if he/she realises there are challenges with the learning, or is he or she delivering the lesson plan?

b) Teaching and learning aids & school infrastructure: The teacher may have great knowledge of their subject, but they may not have access to teaching aids. These support the process of teaching and learning. Whereas it is an expectation that teachers will use the locally available materials, sometimes some teaching aids require procurement. I may have great knowledge of Social Studies, but not have a map of Uganda as a teaching aid, or have markers and manilla paper to draw it. It doesn’t mean I don’t know my subject.

c) Parental and community engagement: What is the quality and quantity of the parents and community engagement in the children’s learning? How does the parental engagement in urban areas compare with the parental engagement in rural districts? A teacher may be effective in class, but a learner will not perform if they are staying in a home with domestic violence. Do the parents in Nakaseke attend parents’ meetings? Do they follow up on their children’s learning with teachers?

d) School feeding: Very related to the above is the issue of school feeding. Many schools in rural areas have challenges with school feeding. If the learners don’t have food, how are they expected to learn? I may be a subject expert, but if Iam teaching a hungry, sleeping class, how will they learn or perform well in exams?

e) School oversight committee’s capacity: All government aided schools have school oversight committees, ie, the School Management Committees, Board of Governors and Parents Teachers Associations. How effective are they in their role of supporting teaching and learning and school leadership oversight? What is the level of education of the chairpersons and members of these committees? How often do they visit their schools?

f) Pedagogy and language of instruction: This is an enabler of teaching and learning, especially for rural schools. Are the teachers in these schools using a learner centred or teacher centred pedagogy? Are teachers in lower primary schools being taught in their mother tongues for ease of learning or do they teach in English to a child who has come from a home where the language of communication is exclusively Luganda?

g) Policy: The ministry passed an automatic promotion policy in UPE schools. This by implication means that all learners must move to the next class irrespective of their performance in their current class. So what should a head teacher or teacher do for a learner that is scoring grade 4 or grade U in P6?

h) School support supervision & quality assurance: School support supervision is another missing link in teaching and learning. How many times do the School Inspectors support supervision in these schools? What about the foundation bodies, the oversight committees, the Local Council members, the head teacher or the parents body? Do these schools have a support supervision system to ensure improvements in teaching and learning, or do they all wait for the PLE, UCE, UACE exams and then be reactive?

In summary therefore, it is very important to note that there are many reasons why a teacher may be a master of their subject content, but not necessarily lead to children learning. Let’s constructively work with the teachers, not against them. They are the solution, not the problem.

Modern Karema Musiimenta, Uganda Country Director, STIR Education.