Prime

Idi Amin reign through the lens

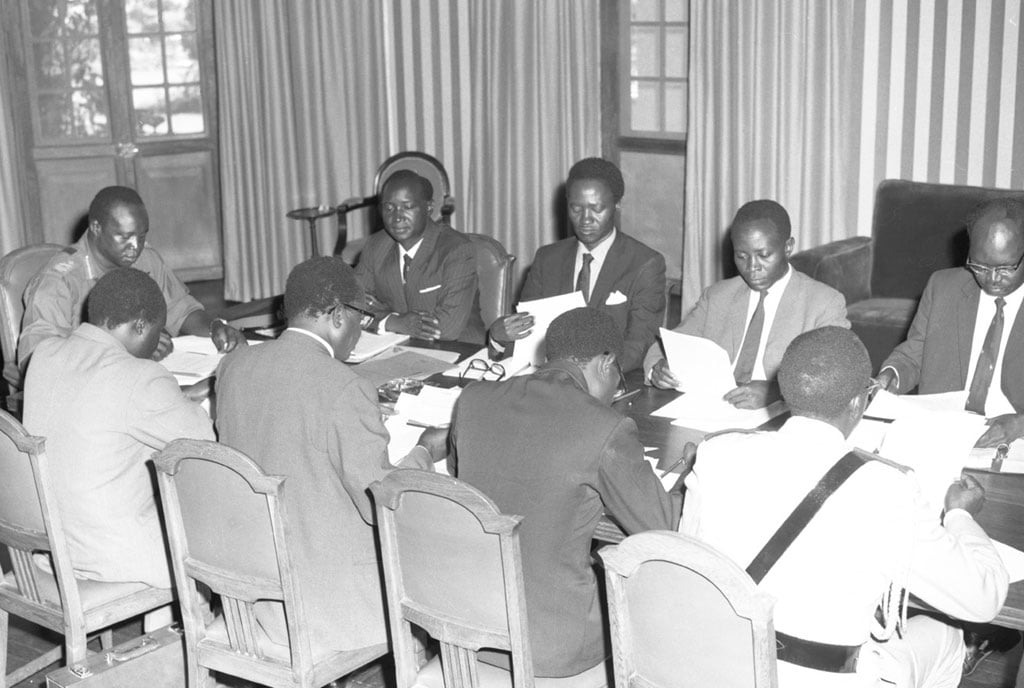

President Idi Amin (left) chairs the first Cabinet meeting of his new government at State House in Entebbe on February 7, 1971. PHOTO/COURTESY UBC TV

What you need to know:

- This month, 50 years ago, hundreds of Asians expelled by Idi Amin’s government flew out from Entebbe International Airport to seek new opportunities mainly in the United Kingdom and Canada.

- In this seventh instalment of our series marking the golden jubilee of the expulsion, Bamuturaki Musinguzi examines a photo collection of how Amin sought to gain support for acts such as the expulsion of tens of thousands of Asians in 1972, among others.

President Idi Amin would not resist the decolonisation wave that was sweeping across the African continent in the 1970s that sought to insist on dignity, self-respect, pride and confidence among the Black people in most of the newly independent states.

Amin’s decolonisation drive of renaming landmarks, water bodies, roads and streets after Ugandan and other African personalities, is partly captured in a new book by Derek R. Peterson and Richard Vokes titled The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin: Photographs from the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation published by Prestel Publishing in 2021.

The trove of recently discovered photographs is a product of a collection of 70,000 negatives from the archives of the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC). The images in this remarkable collection were taken by Amin’s personal photographers between the 1950s and mid-1980s.

Organised into thematic sections, the photographs show how Amin sought to gain support for acts such as the expulsion of tens of thousands of Asians in 1972.

There are portraits of Amin with other leaders, including Louis Farrakhan or King Sihanouk of Cambodia, and with members of his family.

There are also fascinating insights into the ways Amin hoped to promote Ugandan arts and culture, including a food-eating competition in Kampala and ceremonial visits to remote villages.

The 156-page book includes revelatory archival documents recently unearthed concerning the Amin government. Essays by the authors help provide context to the archive.

Decolonising Uganda

According to Peterson and Vokes, the call for cultural self-liberation was widely articulated across the African continent in the 1970s. It was the decade of Black Consciousness, a South African ideology that—in one scholar’s insightful assessment—sought to “instil dignity and confidence worthy of the image of God” in Black people.

In 1972, the Amin government summarily banned the wearing of miniskirts. A year later, another ban, this time around growing bushy beards and the wearing of long hair by men, took root. The Amin government blamed “foreign hippies” for all manner of criminal behaviour, including printing counterfeit money, kidnapping and assassination.

Recalling the banning of miniskirts, Justine Muyingo, a retired a seamstress in Bunamwaya, Wakiso District, said: “The women were forced to adopt long and maxi dresses, which we called Amin nvaako (Amin leave me alone in Luganda).” ‘

She added: “The women looked beautiful, lovely and honoured in the long and maxi dresses that we made.”

Muyingo told Sunday Monitor that young women “who loved miniskirts” were outraged if anything because that was “the fashion of the day.” But Muyingo—whose East Fashions business mainly made women’s and children’s dresses across the 1970s and 1980s from its Nkrumah Road location—said “miniskirts are not good because they can attract rapists and do not bring honour to the women.”

Nineteen seventy-four brought with it the banning of hair wigs. Amin reasoned that they were “made by the callous imperialists from human hair mainly collected from the unfortunate victims of the miserable Vietnam War.” He also believed that they made “our women look un-African and artificial.” he added.

Muyingo, however, says the wig “made economic sense to the women … because … [it] saves you the expense of combing, washing and styling your hair.”

Peterson and Vokes also reveal that “across Uganda, infrastructure was relabelled.” For instance, “in January 1973, workers took down the statue of King George VI, which sat in front of the High Court. The artist and editorialist Eli Kyeyune called it ‘a turning point, whereby colonial symbols have inevitably to give way to indigenous African symbols…’”

One of the iconic images in the UBC archive shows Amin and other dignitaries marching in Kampala on the occasion of renaming Queen’s Road as Lumumba Avenue. This was in honour of Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo or DRC) on January 18, 1973. Amin is also seen unveiling the road sign bearing the name of the African patriot.

“President Amin yesterday told the nation that the policy of his government is to give the people of Uganda and Africa as a whole a sense of self-respect and pride in themselves,” the Voice of Uganda newspaper reported on January 19, 1973, attributing Amin to have said verbatim thus: “We believe it is time we took stock of ourselves with a view to restoring our cultural heritage, human dignity and respect which have hitherto been denied us by forces of imperialism and their agents.”

Amin (centre) marches during a function to rename Queens Road as ‘Lumumba Avenue’ in Kampala on January 18, 1973. PHOTO/COURTESY UBC TV

Amin insisted that the names given to roads or other places of public interest should reflect “our African values and national aspirations.” He added that “Patrice Lumumba went down in history as a true son of Africa, who fought relentlessly for the deliverance and salvation of his people from the yoke of imperialism.”

Renaming water bodies

On July 17, 1973, Lake Edward took on Amin’s name. The Voice of Uganda’s headline sreamed “authenticity over colonialism.” Later, Lake Albert at another colourful ceremony at Mahagi Port in Zaire was christened Lake Mobutu Sese Seko. At both functions, Amin disclosed that during their overnight long discussion, he and President Mobutu had agreed to strengthen the relations between Uganda and Zaire. The first step was the abolition of fishing restrictions and visas requirements between the two countries.

ALSO READ: The culinary influence of Asians

Declaring the renaming of Lake Idi Amin Dada, General Mobutu said Zaire considered the occasion very important. Zaireans, he added, believe that it was legitimate to rename important national historic places after indigenous names. This, he proceeded to note, was another step in the decolonisation of the minds of the people and “the restoration of dignity to our countries.”

Outlining the historic background of Lake Mobutu Sese Seko, Amin said it had been named after King Albert in 1900 when the lake, Arua, Pakwach and other towns were under Belgian Government until 1926 when they were taken over by the British.

Amin told the people that it was high time the lake was renamed after an indigenous name because when it was taken over by the British from the Belgians they did not change the name.

Mobutu had earlier—accompanied by Amin—laid the foundation stone of the terminal building of the Arua International Airport Terminal building in Arua in north-western Uganda. They later attended the ceremony of renaming of Arua Road as Mobutu Sese Seko Road at the Pakwach Junction.

Lake Albert and Lake Edward are located in the Albertine Rift, on the border between Uganda and the DRC. Lake Albert is shared by Uganda and the DRC. The indigenous people near Lake Edward and Lake Albert in Uganda call the water bodies Mwitanzige (killer of locusts).

In 1972, Amin renamed Queen Elizabeth National Park as Rwenzori National Park and the Murchison Falls and its national park, he renamed Kabalega Falls and Kabalega National Park. After his downfall, the names of the parks reverted to their colonial names. A few roads like Lumumba Avenue have retained Amin’s legacy in this regard.

Sports, performing arts

A section in the book, which opens with a series of photos illustrating Amin’s rise to power and the enthusiasm with which the 1971 coup was greeted, is devoted to “the politics of culture.” It shows how the Amin government’s revival of traditional performing arts helped prove the regime’s anti-colonial credentials. Never before had artists enjoyed such a prominent place in public life.

It shows how the Amin government’s revival of traditional performing arts helped to prove the regime’s anti-colonial credentials. Never before had artists enjoyed such a prominent place in public life.

At the same time, Amin placed sports—especially football, boxing and wrestling—at the centre of public life. According to Peterson and Vokes, these games projected a kind of “muscular masculinity.”

The photographs in the “The Public Life of a Family” section illuminate the variety of ways in which Amin enlisted his children in the service of his regime. In these and during many other occasions, Amin deployed his children to puncture the seriousness of diplomacy, undermine the solemnity of public occasions, and transform abstract political alliances into convivial, social relationships.

Foreign policy

Amin was an enthusiastic and indiscriminate participant in international affairs. The “On the Front Lines” section shows Amin as a global actor and not the president of a small and provincial country.

The photographs reflect the Amin government’s interest in making its global role visible. An astonishing range of unlikely world leaders visited Uganda during those years. These included the ruler of Somalia, Said Barre; Libyan President Muammar Gaddafi; Nguyen Hu’u Tho, the chairman of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam; and Norodom Sihanouk, the deposed ruler of Cambodia. All these men were treated to state visits, and all of them were photographed extensively.

The expulsion of the Asians

In August 1972, Amin summarily decreed the expulsion of Uganda’s entire Asian community, obliging nearly 80,000 people—many of whom had lived in Uganda for generations—to flee the country within 90 days. Amin called it the “War of Economic Independence.”

For Ugandans of Asian descent, Amin’s decree was a disaster. Thousands of people jammed the terminal at Entebbe airport, as Asian families looked to take refuge in Britain, Canada, India or in other places offering succour. It was there, at the airport, that many of the gripping photographs depicting the Asian expulsion were made. They depict people in dire straits, rendered suddenly stateless, desperately looking towards a future they could not predict or control.

According to the authors, section photographers made some of these images, but they were subsequently purged from the archive. The photos that remain are concerned with the criminality of the men and women, who Amin had expelled. These photos focus on Asian businessmen who had been caught smuggling cash and other goods out of Uganda, against government regulations. Others show the Asians who were accused of hoarding cash.

About the research bureau

“The State Research Bureau” section is about the notorious men of the State Research Bureau (SRB), who were responsible for pursuing the government’s internal enemies. These agents—who numbered 1,000 men by 1977—enjoyed enviable advantages. They earned $350 per day for their work, got free-lodging in state-run hotels, and drove in fast Toyota cars kitted out with radio equipment.

The Australian Commissioner at the time thought the SRB to be a “macabre euphemism for a killer squad.”

The photographs were taken in April 1980, about a year after the fall of the Amin regime. They show the infamous SRB building and horror torture chambers.