Prime

Innovation and investment in arts, culture way to go

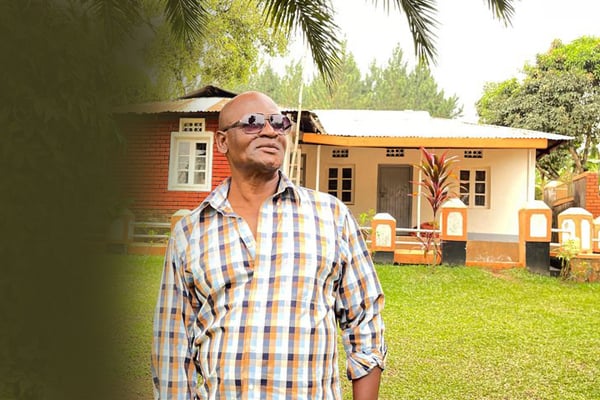

Daniel Komakech (centre) directs a movie during a shooting in Gulu City recently. Practitioners estimate that about 200 local films are produced in Uganda per year. PHOTO / FILE

What you need to know:

- Africa’s film and audiovisual sector remains—in the main—historically and structurally underfunded, underdeveloped and undervalued, according to a UN report. Bamuturaki Musinguzi explores what can be done to change this status quo.

The first complete mapping of the film and audiovisual industry in 54 states across the African continent shows that the sector—which currently employs an estimated 5 million people and accounts for $5b (Shs17.7 trillion) in GDP—remains largely informal and untapped.

The UN cultural agency, Unesco, has despite, or in fact because of that status quo, proffered strategic recommendations to help the sector achieve its estimated potential of creating 20 million jobs while contributing $20b to Africa’s combined GDP.

In a publication titled The African Film Industry: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities for Growth, Unesco cites Nigeria’s film industry popularly known as Nollywood. The industry churns out nearly 2,500 films each year off the back of its own viable economic model. Its success has, however, been rarely replicated on the continent.

According to the report, published with the support of the government of the People’s Republic of China, Africa’s film and audiovisual sector remains—in the main—historically and structurally underfunded, underdeveloped and undervalued.

Regulations, when they do exist, are sometimes seen as obstacles rather than enablers. Many aspects of these industries remain informal.

The report further adds that a dearth of enabling policies possibly constitutes the most crucial impediment to the development and growth of the continent’s film and audiovisual sector. Currently, the organisational structure for cultural policy administration appears—in most African countries—quite fragmented.

Untapped potential

This outlook makes it difficult to design concerted short-and long-term policies and strategies. Many countries lack an empowered ministerial body devoted to culture and the creative economy.

With regard to the film and audiovisual sector, 30 out of 54 African States (55 percent) currently have a national film policy. Only 24 (44.4 percent) have a film commission.

“There is a need for African countries to recognise the sector by mainstreaming the sector into the nation’s policy agenda for economic, social and technological enhancement of countries prosperity,” the chief executive officer of the Kenya Film Commission, Timothy Owase, tells Sunday Monitor.

The report shows that globally, cultural and creative industries (CCIs) are estimated to generate about $2.25 trillion annually (three percent of the global GDP) and employ 30 million people worldwide.

Africa and the Middle East, however, represent only about three percent ($58 billion) of this global trade.

“Considering the dynamism and global cultural influence of Africa’s creative sectors, this constitutes a major untapped opportunity for African countries seeking to diversify their economies,” the report states, adding: “CCIs are also proven to be one of the most innovative and resilient sectors in times of crisis, employing a large number of young people and women in high-skilled jobs while also encouraging entrepreneurship…”

It further adds that national governments can have a major impact through policy and the development of enabling environments. There are positive signs that countries across the continent are waking up to the potential of their creative industries, and more specifically of film and television. To this end, at least seven countries—including Zambia, Zimbabwe and Sudan—are currently working on draft film policies. A number of others are updating existing documents.

Unauthorised use

Piracy, however, remains rampant, with two-thirds of countries estimating that at least 50 percent of the potential revenue of the sector is lost to the illegal exploitation of creative audiovisual content. This, in many cases, deters structured investment.

“Piracy impacts earnings by intellectual property owners. It also infringes on the rights of the holders. Piracy affects industry growth as income circulates to wrongful recipients of income and it paints the industry as informal rather than formal. There is a need for governments to adopt stringent copyright laws and enforcement mechanisms,” Owase says.

Ugandan film director/producer at Bish Films Limited, Matt Bish, describes piracy as “an old story that keeps coming back to haunt filmmakers.”

He adds: “Some filmmakers have no idea what intellectual property and copyright is all about or the film kiosks or street vendors don’t understand that the films they sell have to be acquired through channels that are legit. Nobody is telling them these things. They feel they have every right to sell a copy of the film as long as he has spent his own money to produce multiple DVD disks.

“However, this has slightly turned for the better in the last two to three years in which many film sellers have been cracked down and made to pay for what they have stolen. This, of course, greatly affects what you make at the end of the day. If you found your film on the streets before you released it, that would mean you are not going to get paid. Production costs and, or any profit, is thrown out of the door.”

Unesco’s report further shows that only 19 African countries (35 percent) offer financial support to filmmakers. The report further reveals the existence of weak or non-existent governmental incentives in some countries in the Eastern African region.

Public funding for the film industry, it adds, stands at 14 percent.

“Film incentives offer a destination with a competitive edge, hence deliberate policy frameworks that provide a country with incentives to attract inbound international productions, as well as incentives to promote development of local productions, as well as for igniting growth of the sector,” Owase says.

Government support

Bish says: “Every country requires a form of incentive in order for it to flourish in the film industry. Americans had their input back in 1910, most European countries still get government incentives to-date.’

Bish says incentives are “a vital form of input for any film industry here in East Africa.”

“Uganda is on the path towards that similar template and hopefully it pays off. It is known how expensive the industry is and whichever way we look at it, the film industry can’t flourish without government incentives,” Bish notes.

“It has taken long for most African nations to appreciate the value of the creative economy; hence most African nations lack enabling frameworks for co-productions. I do not agree that there is limited potential. The potential is in abundance, it however, requires to be unlocked through enabling frameworks such as policies and other relevant laws,” Owase argues.

Bish believes “signed treaties between countries that bare the absolute full functionalities of the film industry” can actualise co-production undertakings.

“Uganda particularly has had its share of issues in building the ideal infrastructure. Countries such as Kenya and perhaps Rwanda, have made it a priority to build these things so as to grow their industries,” Bish reveals.

Owase concurs that the film and digital infrastructure in some Eastern African countries is “weak.” He adds that this negatively impacts “content commercialisation.”

There is, nevertheless, some light at the end of the tunnel. Bish specifically points out the “many VOD (video on demand) and streaming platforms which are constantly licensing films and television content around the East African region and Africa.” He, however, hastens to add that “Uganda hasn’t yet developed a great digital streaming service despite the well informed public and the young generation, which is into everything digital.”

All things streaming

According to Bish, Covid-19 pandemic restrictions such as lockdowns highlighted the benefits of streaming.

“Streaming giants such as Netflix made a lot of revenue due to the closures of cinemas around the globe,” he noted, adding: “The internet has changed the way we deliver our movies and this has to change in Uganda and its neighbours.”

He further says: “We end up relying on a few streaming companies such as iflix, Showmax, among others, and until our local filmmakers learn the importance of all these digital platforms, they will go for the more expensive delivery format which is quickly dying out— DVDs.”

The film industry has also been dogged by a lack of critical mass insofar as training of its key players is concerned. It also does not help matters that the curricula remain more theoretical than practical. The industry’s players do not keep up with the pace of technological advancement in more developed markets. And few countries have public institutions that offer post-secondary degree or diploma programmes dedicated to film.

“This means there is a need for countries to mainstream sector education into national systems with an objective to produce more skilled manpower for quality storytelling and business,” Owase says.

Regarding freedom of expression, little progress has been observed in recent years—87 percent of respondents report that there are explicit or self-imposed limitations to what can be shown or addressed on screen.

From an infrastructure perspective, according to the report, the distribution segment of the African film and audiovisual value chain is undergoing profound changes. Africa’s cinema network is already the least developed in the world, with 1,651 screens.

As the Covid-19 pandemic shut down cinemas across the continent for the better part of 2020, it exacerbated the worry that cinema distribution may forever fail to take off in some countries.

“…Africa has one cinema screen per 787,000 people compared to one per 7,500 in the United States and one per 19,000 in China. This is despite a growing appetite for the cinema experience and very dynamic film production sector,” Nigerian filmmaker and MultiChoice Talent Factory Director for West Africa, Femi Odugbemi, observes, adding: “Why is this important? Africa cinema cannot be elitist and unaffordable for its masses. Beyond entertainment, cinema is cultural practice. In its stories and representations, our audiences’ world expands.”

Cinema and multiculturalism

According to Odugbemi, “Cinema fosters understanding and perspectives of our common humanity necessary for us to embrace the multicultural, multi-racial diversities of our world. In disadvantaged continents such as Africa where our ‘story’ has been shaped negatively for centuries, access to cinemas where our stories have access and our people have opportunity is key to our emerging generation of young entrepreneurs and innovators.”

“The African story needs a thriving affordable cinema within the reach of its populations. Investment in cinemas in Africa is also important so that the African filmmaker can be better rewarded with sizable return on investment. The online digital platforms are currently the only spaces where African filmmakers are getting some reasonable margins on their work. But licensing fees for the generality of films on digital platforms are trickles compared to what cinemas chains can deliver in a few weekends of sales for a strong and well-promoted film title,” Odugbemi adds.

The other challenges highlighted by the report include gender equality, internet connectivity, and Africa’s delayed transition process from the analogue broadcasting system to digital terrestrial television (DTT), among others.

Digital revolution

The real game-changer for the African film and audiovisual industry though, is the ongoing digital revolution. This started some 20 years ago and was accelerated by the pandemic. Today, technology, affordable digital film equipment and the new ability to distribute but also monetise content directly to consumers via online platforms (from YouTube, other social media and Netflix to local mobile video services) is giving rise to a new economy for African content creators who choose to bypass traditional gatekeepers.

In countries such as Kenya, Rwanda, Ethiopia and Senegal, for instance, new generations of filmmakers are now able to live from the online revenue generated by their work.

The UN report recommends that the Nollywood model of development be co-opted by other African countries to build fully home-grown, self-sustaining commercial industries.

“Because a key prerequisite for this model is a substantial volume of sales, it is better suited to countries with large local markets such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia or Tanzania,” the report states, adding: “However, the recent success of Rwandan web series proves that even countries with smaller markets can adopt this approach if they are able to tap into their larger diaspora communities and are realistic about matching production budgets to revenue potential.”

According to the report, the Nollywood model is characterised by its low-cost, speedy production mode, which enables producers to complete a film for as low as $15,000 (Shs53m) in a matter of weeks.

“Even in Nigeria, producing a film for such a restricted budget is a stretch: it requires ingenuity, resourcefulness and stamina from both cast and crew, all working around the clock in conditions that would be unacceptable elsewhere,” it notes.

“As in other commercial markets, such as China, India and the United States, Nigerian production budgets are also privately funded. Producers may re-inject the proceeds from a successful project into a new one or raise money from individual private investors, such as friends, family or high income acquaintances. Brand sponsorships and product placement are possible for some of the larger productions,” the report concludes.