Prime

Media houses should skill newsrooms to survive - expert

Carol Azungi Dralegah. PHOTO/COURTESY

What you need to know:

Carol Azungi Dralega is an Associate Professor and head of research on the Global Journalism programme in the Department of Journalism, Media, and Communication at NLA University College, Norway. During the Covid-19 pandemic, she co-authored two books; ‘Health Crises and Media Discourses in Sub-Saharan Africa’ and ‘Covid 19 and the media in Sub-Saharan Africa: Media Viability, Framing and Strategic Crisis Communication.’ She has prior work experience as a sub-editor and reporter at Uganda’s two leading dailies: New Vision and Daily Monitor, respectively. In this interview with Daily Monitor’s Edgar Batte, she talks about the future of journalism in the face of technology and artificial intelligence.

What did it take for you to co-author and edit two books during the Covid-19 lockdown?

I co-authored both books with a colleague from Uganda Christian University (UCU), Dr Angella Napakol, who is part of a six-year collaborative project between NLA, UCU, University of Rwanda and University of KwaZulu Natal on Preparing Media Practitioners for a Resilient Media in Eastern Africa.

Dr Napakol had travelled to Norway in 2019 for a post-doc research in relation to the project. Covid-19 got her there. As the pandemic advanced, shutting down all sectors, including the media, I remember asking her if we could try to capture its novelty and devastation on media eco-systems on the continent.

That’s how the two books were born. We wrote a proposal to Springer Nature on Covid-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa, its impact on the media and it was rejected at first. Their fear was an anticipation of too many covid books. We decided to broaden it to health crisis with the aim to capture existing as well as the current pandemic. We received more than 36 chapters. We were so amazed at the caliber of scholars and excellent scholarship submitted to us. But Springer accepted 16, which were published open access. The second option was to drop the rest or find another publisher. We successfully approached Emerald Publishers who captured 13 chapters. As you can imagine, it took conviction, persistence, continuous engagement and hard work to have two books published around the same time.

Which are the anchoring thematic concerns of bringing out these publications?

The dominant theme is health crises and media discourses. Covid-19 issues take the lion’s share, naturally as this is the current health crisis. In addition, we have articles on other health crises such as HIV/Aids, Ebola, malaria, neglected tropical diseases as well as silent health crises such as mental health. The articles are anchored to the unique African experience, histories, impact and implication of the crises in social, economic, technological and political contexts related to media and society. Here, issues such as the political economy of the media, especially media viability as well as media framing, health crisis communication, critical watchdog journalism and constructive journalism are key issues taken up in both books.

Talk to us about the effect of mental health because of Covid-19

Several chapters include insights from journalists sharing their experiences from the frontline. In fact we dedicate both books to those who lost their lives at the frontline of one of the biggest stories of our lifetime.

From a personal and professional level, as frontline workers, journalists were exposed to the depressing topic they had to cover, patients, devastating developments on a day-to-day basis. Some journalists lost their colleagues to the virus. This was traumatic an experience with consequences to mental health.

From an industry level, we also know that journalism is under crisis. This crisis has been ongoing for a while now and it is about survival, especially from the financial basis. The question has been - how do the media continue to sustain themselves in the face of increasing technological changes, dominance of big technological companies ‘doing journalism’ and the rise in citizen journalism. This scenario has meant, among other things, that the traditionally known revenue sources through advertisement and sales have increasingly dwindled. Covid-19 exacerbated this challenge as many customers moved online – the paradox being that this move did not come with paying customers. So, the struggle for survival at industry level is cause for angst for many in the profession.

Covid-19 brought along many shifts. We have known a lot of journalists losing their jobs. We have newspapers such as Avusa in South Africa, which lost between 500 and 600 journalists in its production chain, so loss of jobs, especially in the economies where there are no support structures was quite devastating and cause for mental health concerns - particularly those uncontracted journalist like freelancers and photographers.

Dr Angella Napakol, who co-authored two books with Carol Azungi Dralega. PHOTO/COURTESY

In your view, where does journalism go from here in face of technology and artificial intelligence?

I think that technology and its development is indomitable, we cannot wish away and as such, preparedness is key. It is vital to develop our systems, processes as well as investing in skilling our newsrooms and journalism classrooms to adapt to the new changes.

There’s a need for management adaptation and a leadership that embraces change and prepares the workforce for that change, for instance, through training, infrastructure and structures.

Several news media have instituted innovative structures, including for instance, employing, computer scientists, programmers and software developers, IT experts, visual analysts as integral parts of the newsroom.

Concepts such as ‘digital first’, ‘media convergence’ are things of the past, especially in large media houses. We are now seeing an algorithmic-turn in journalism practice where Artificial Intelligence, metrics and data are integral parts of agenda setting and cost-effective news production and dissemination as well as financial sustainability. The extent and nature (stage) of AI incorporation varies from newsroom to newsroom.

Often policies play catch-up, what we need are also up-to-date and prudent policies that guide and support these emerging processes. Policies that ensure foundational journalistic values such as information as a public good, representation of marginalised groups, promote human rights and democracy and policies that guard the watchdog functions of the media. As well policies that attend to ethical concerns such as fundamentals of privacy but also recognise and guard against other flaws in AI-use.

From where you sit as a consumer, what are you looking for when you listen to radio, watch television, or read the newspaper?

When it comes to radio, for instance, I am looking for information that is well verified, that I can trust because decisions I make may depend on that. So the media needs to be trustworthy, fragmented information that attends to audience’ needs and at the same time unifies us as people is also very important.

Which information is important to you?

It depends, if you are talking about elections, I want to hear all spectrum and I would like information that reaches out to everyone and not just to the elite. I would also look for a radio programme that encourages participation. I should be able, for instance, to call in and air out my views instead of sitting there and just listening.

What about the newspaper?

The core of journalism lies in trustworthiness. Are you able to perform those normative functions of the media? I want to read about, for instance, a corruption case that has been dug up against all odds and shared. As a citizen, I want to read that news that has been verified and it has all voices including the marginalized voices because some voices are not so vocal like the women, youth. I want to hear all voices as sources but also as an educator, I am critical of sources of stories and issues of representation.

What is your verdict about the state of the media in Uganda?

I think we have come a long way despite economic, infrastructural, technological and political bottlenecks.

I worked for Monitor as a city correspondent before I moved on to New Vision. My longitudinal observation is that the overall critical functions are not as sharp as they used to be, especially when I first started working in the mid-90s. I would attribute that to the draconian political climate that has and continues to bog the media today.

Contrast for us the time you joined journalism and what’s happening today?

Technology has changed a lot. By the time I graduated in 1996, newsrooms were using typewriters and that is the kind of newsroom we were being prepared for. I remember in year one, our class of 20, were handed typewriters, which we amateurishly pounded with index fingers. When I joined New Vision as a sub editor, that’s when computers were being ushered in. It was the phase of big computers with floppy discs and dialed up Internet. Many layers of the production process were being phased out and we lost so many typesetters, copy editors, etc. We did not have social media, there was no media convergence as radio, TV and newspapers operated autonomously – such was also our training at university.

Discussing gender mainstreaming and framing of media in public discourses, what should journalism do differently?

Editors and journalists need to understand that gender is cross-cutting. It cuts across politics, business, sports and all beats. Any news item must consider its gendered implication because issues affect men and women differently. I would encourage journalists to have this awareness and transmit this further to society. Using gender sensitive sources is another way to make stories relevant to both men and women. Journalists need to look out for the gender implications of each story but also in terms of employment and newsroom cultures to avoid the ongoing leaking pipeline – that show a good number of female journalism students, but the numbers begin to dwindle the moment they step in the newsroom as well as between newsroom and boardroom. Something must be done about that.

Do you think that journalists will have jobs in 10 to 20 years given the current waves of artificial intelligence?

Machines don’t think as us, they don’t analyse critically neither can they capture the nuances in issues. All they do is based on data and what they are taught or programed to capture. If you have a good set of data, the machine will use it and send out a story, but it misses the human touch and the social cultural impulse, so we will still need journalists as important contributors to journalism.

How Dralega chose media as her profession

Talk to us about who Carol is as a person?

Carol Azungi Dralega is one of 10 children, born and raised in Uganda. Currently she lives and works in Norway. She is a teacher of journalism, media, and communication primarily at NLA University College in Norway and sometimes teaches and supervises students at Uganda Christian University (UCU) and soon University of Rwanda. “My Philosophy as a teacher is that I do not know everything and, therefore, believe my students know quite a lot and I want to learn from them as well. In line with that, I embrace a participatory approach to learning”.

To people who know her closely, she would describe herself as an extrovert and introvert to those who do not know her.

What was lifelike growing up and what memories do you carry?

When I talk about growing up, I remember my dad, Mr Jerome Dralega, as one of my heroes and role model, the one who inspired me to be the kind of a person I am. As much as I used to be young and silly like disobeying my dad from going out with friends, to play beyond time and being punished for it, I respected authority. I followed what my teachers taught me, religiously, and I think I was a very good student. I knew education was key to success, so I had my sights set from an early age.

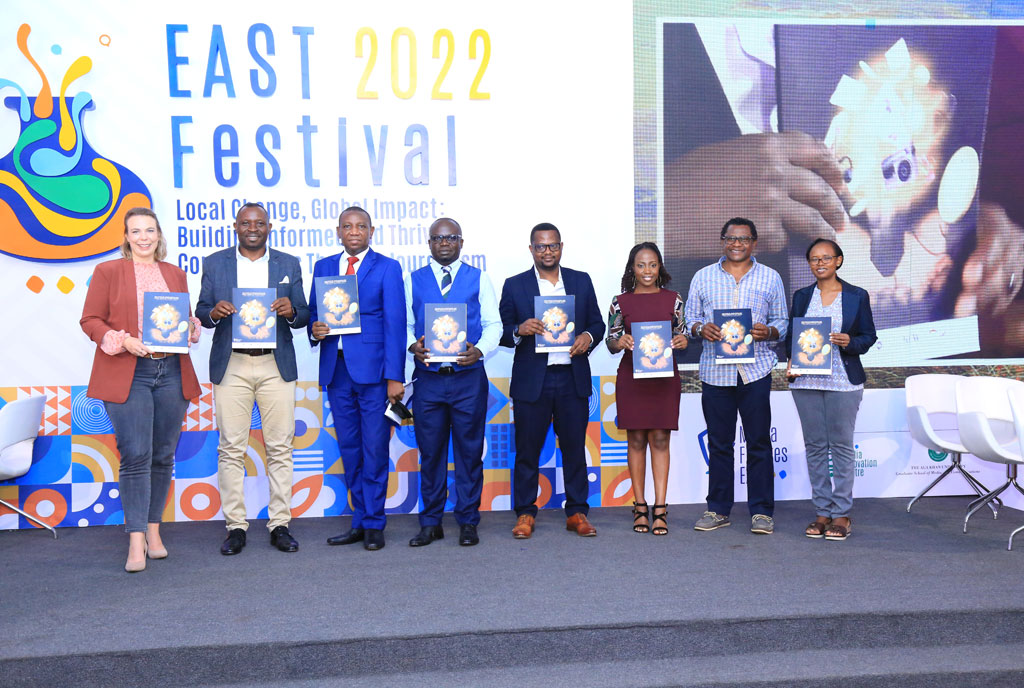

Carol Azungi Dralega during the launch of one of her books at NLA University College on November 7. PHOTO/COURTESY

Why did you choose media?

It was by mistake. I did my Senior Six in Kibuli Secondary School and I didn’t think I was going to pass very highly. I had applied for Public Administration as my first choice because my dad was a public administrator, and education as second choice but I got very high points that they just put me in Mass Communication – then a new and prestigious course offered at Makerere University.

My dad wanted me to do law and I had the points, he even tried to get me registered into law but it didn’t work out. He was quite disappointed that I did journalism and I remember he had asked me if reading news on TV was all I wanted to do in life. Of course he didn’t understand the whole profession and by that time, it was new.

Tell us about your school time and life…

I went to several boarding schools and in era when there were a lot of shifts in political power, it was so bad. My dad had taken us to some schools in Buganda, and later to Busoga and due to political instability, it was difficult to reach us. I remember, once on our way home from school, at one of several road blocks, a solder throwing a baby into the furious dam in Jinja because, its mother had hidden money, they had been asking all passengers, in the baby’s diapers. Another incident was when a notorious solder at another road block, was shooting his gun rested on top of a kneeling man’s head, and laughing profusely. Such memories are still fresh.

On the happier side I did sports and as a sports personality, you are much loved. I played basketball, handball, netball and hocky all my school life all the way to Makerere University. At University, I was the captain of the basketball team. I also did well in class.

Tell me about your journey to Norway

I was in New Vision and in one of those editorial meetings, where they would usually share information on short refresher courses, an editor had mentioned some short courses in Norway.

After the meeting everyone stood up and left. I picked up the papers and applied because I needed a breather. That is how I ended up in Norway for six weeks in 1999 for an international Summer School Course in Media Studies. My participation in this course opened my eyes to this kind of student-centered and participatory pedagogy I was talking about.

The lecturers there were being referred to by their first names, were very down to earth, very brilliant, the lectures were very participatory, I was inspired to do my master’s which applied for the following year and got and the rest is history.

Now that you have come back to Uganda as a highly educated woman, is there still any place for you?

I actually come home 2-3 times a year because east or west home is best. I come to teach and to meet my family and friends, which is always nourishing.

How are you juggling academics and family?

I have a wonderful husband and I have been traveling quite a lot since my children were young. My first trip happened when our first born was only five months old and breast feeding. I went to Finland for a conference as part of my PhD. Like I said, my husband is amazing. He is the best person I could leave my kids with but of course in Norway, we don’t have maids; father and mother have to do everything, so you have to be so structured.

Do you have any words for women who are interested in academia?

Due to the leaking pipeline, few women go for higher education and academia. So, I would encourage young women to go for it, we need diversity. Academia and the vocation of knowledge generation and nurturing the future generations needs your input and representation. We need role models, inspirational figures and change agents in academia.

.