Prime

Gen Okello calls for peace talks

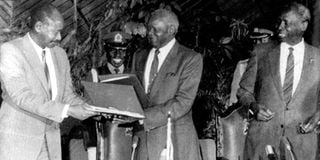

Gen. Tito Okello-Lutwa (C) exchanges peace agreement documents with NRM/A’s Yoweri Museveni (L) in Nairobi in 1985. Looking on (R) is Kenyan President Daniel arap Moi, who chaired the talks. COURTESY PHOTO

What you need to know:

Regime’s appeal. Just after taking over the government, the Okellos plan to have an all-inclusive regime by involving all political and military forces in peace talks.

When Gen. Tito Okello and Brig. Bazillio Okello - who masterminded the coup – overthrew the Kampala regime on July 27, 1985, they set about forming a new administration.

The new government came with some changes. Tito Okello added Lutwa to his name, while Bazillio Okello added Olara. Their titles also changed. Gen. Tito Okello-Lutwa was now the chairperson of the Military Council and head of state, while Brig. Bazillio Olara-Okello was promoted to Lieutenant-General and made Chief of the Defence Forces.

The Okellos were quick to call upon the military and political forces to form a national administration and steer national reconciliation and nation-building. But the National Resistance Army rebels led by Yoweri Museveni remained in the bush and would be a pain in the neck for Gen. Okello-Lutwa’s regime.

Thus, Gen. Okello-Lutwa publicly invited the NRA guerillas and other fighting forces for peace talks.

Three days after the coup, Gen. Okello is reported to have met President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania in Dar es Salaam to ask him to mediate the talks with the NRM/A.

Ambassador Bethuel Kiplagat, the then Permanent Secretary in the Kenyan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in his review of the peace talks published in 2010, says: “Dar es Salaam and Nyerere were obvious choices for three reasons. First, Nyerere was popularly seen as a benefactor to Uganda for his role in opposing and overthrowing the military dictatorship of Idi Amin.

Second, Gen. Okello was himself a former colonel, who escaped Amin’s purge against the Acholi and Langi and found refuge in Tanzania. He returned with the Tanzanian forces that overthrew Amin. Third, Nyerere was an African elder statesman, whose honesty and influence were second to none in East Africa.”

But Museveni and his group are said to have failed to attend the Dar es Salaam session, a thing that media reports later pegged to Nyerere’s long-term association with Milton Obote, whom the NRA had gone to the bush to oust.

When the talks fell on rocky grounds, the Kampala government was quick to run to its neighbour in the east - Kenya, then under the stewardship of Daniel arap Moi. The venue was moved to Nairobi and the talks would resume from August 26, 1985 to December 17, 1985.

The NRM/A group, which was led by Museveni, comprised Eriya Kategeya, Mathew Rukikaire, Zack Kaheru, Sam Male, Gertrude Njuba, Kirunda Kivejinja, Grace Ibingira, Abu Mayanja, and Ruhakana Rugunda, among others.

The government of Uganda was represented by the Military Council headed by Gen. Okello-Lutwa accompanied by J. Bugingo, Major Kiyengo, Sam Kutesa, Brig. Oketcho, Paul Ssemogerere, Olara-Otunnu, and Brig. Wilson Toko.

The Military Council was a coalition of armed groups, the major one being the national army, the Uganda National Liberation Army (ULA). The others included the Federal Democratic Movement of Uganda (FEDEMU), the Uganda Freedom Movement (UFM), the Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) and the Former Uganda National Army (FUNA).

The Nairobi Peace talks weaved around a power-sharing module that would regulate the composition of the Military Council that controlled the Ugandan government.

As the talks kicked off, the parties agreed to a cease-fire, to be implemented by their commanders within 48 hours of the signing of the agreement. They also resolved to form a coalition government that would make Okello-Lutwa the chairperson of the council and head of state and Museveni, as the vice-chairperson.

The members named representatives to the Military Council. The UNLA was given seven seats, excluding Gen. Okello’s; NRA was given seven, including Museveni’s post, and UFM and FUNA, each got two seats.

However, the talks are said to have been characterised by undertones of mistrust. Museveni, for example, reportedly described the previous regimes as “backward” and “primitive” and also had allegedly refused to hold talks with the Military Council, whom he referred to as “criminals”. The commission, in a rebuttal accused him of delaying the talks ‘unnecessarily’.

The accusations in the early stages of the talks could have set a negative tempo that would manifest itself in the following days or even years.

Museveni is said to have missed the talks for three consecutive days after reportedly going to Europe and when he returned, he, besides other new demands on the agenda, said because Gen. Okello was a commander of a faction of the army, he could not be the Head of State. This jeopardised the talks because the agenda had spelt out that Gen. Okello would be the chair of the Military Council and Museveni the vice chair. Moi also said the back-and-forth manner in which the NRA was conducting issues was “disrespectful”.

But that was not the end, Olara-Otunnu, the then Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Military Council, confronted Museveni, who had accused the government of working with pro-Amin soldiers. He pointed to Museveni’s pact signed in Tripoli, Libya, with former pro-Amin soldier and minister, Brig. Moses Ali, also a former senior minister under Amin, and Abubakar Mayanja.

Olara-Otunnu also received his fair share as Museveni said he did not understand the meaning of a “revolution” and that Otunnu had defended Obote’s bad human rights record while he was an ambassador at the UN.

With the accusations and poor foundation, the talks were bound to collapse by the end of 1985, and that is precisely what would happen.

Continues on Monday