Prime

Lessons from Amin on modern-day dictators

What you need to know:

Picking a leaf. In the last of a three-part series by Prof. Ali Mazrui as captured in Between Development & Decay: Anarchy, Tyranny and Progress under Idi Amin, modern -day dictators are given lessons from Amin’s rule and fall.

Kampala

The role of Idi Amin helped to erode the legitimacy of western hegemony by challenging it and defying it in a variety of ways.

First, the myth of Western invincibility was receiving severe knocks from Amin’s sustained strategy of irreverence. The biggest act of defiance still remained the expulsion of British Asians and the nationalisation of some British firms and property.

However, there were other instances of calculated impertinence whose total effect amounted to the gradual erosion of the Western mystique. Amin defied diplomatic protocol time and again. He was capable of sending a cable to Richard Nixon wishing him a speedy recovery from Watergate and another cable to Prime Minister Golda Meir, telling her to pull up her knickers against the background of the October War in the Middle East in 1973.

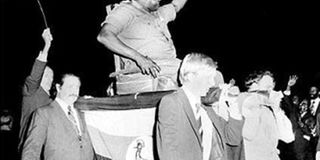

Amin converted the whole world into a stage, trying to force some old imperial myths through the exit door, and to bring in new defiant myths of black assertiveness. His highly publicized picture, being carried on a big chair by four white men, ridiculing Rudyard Kipling and his vision of the White Man’s Burden, was part of Amin’s theatre of the absurd.

Another strategy to ridicule the world system was to keep the world guessing. His games with the world news media in the summer of 1977, in relation to the Commonwealth Conference of Heads of Government and Heads of State in London, was one such instance. Would Amin come to defy the diplomatic ban against his participation at the Commonwealth Conference which the British government had decided to impose? His radio in Uganda issued statements which implied that he was about to land in France, and then go by boat to Britain; or was about to land in Ireland, and find his way to the Commonwealth Conference: A deliberate comedy was unfolded upon the world stage, poking fun at the world and its ways.

Amin also employed the periodic strategy of holding a hostage or hostages, or permitting Western missionaries and teachers within Uganda to be seen as a pool of future hostages against Western power. In more than symbolic sense, much of the Third World now is held hostage by the Northern hemisphere. The super powers in particular are in a position to destroy the rest of mankind in their own rivalries for hegemony.

Economically, the Third World is held hostage by the capacity of the Northern hemisphere to decide the destinies of the economies of the South. A decision by the North to drink half as much Ugandan coffee could have speeded up his fall - for better or for worse. In short, drinking habits among Western Europeans and North Americans, or how much chocolate the affluent North is interested in this year as opposed to last year, could either put economies in the South under severe strain or create a temporary boom here and there.

Symptom of moral cleavage

Apart from the oil-rich Third World countries, almost all other Third World countries are, in a fundamental sense, held constantly hostage by the tastes and consumption patterns of the northern hemisphere.

Therefore, when Idi Amin held a Westerner like my friend and former colleague, Denis Hills hostage, there was a profound reversal of roles. Or when Amin threatened to bring all Americans within Uganda to Entebbe Airport, there was again a sense of the mighty being held hostage by the whims of a Third World tyrant, just as the Third World is held to ransom by the vagaries of Western consumption patterns.

It is partly because of these considerations that Amin emerged as a symptom of the profound moral cleavage which both reinforces modern industry and the fumbling economies of the developing societies. And for this reason, Idi Amin was to some extent no less a preacher than Jimmy Carter, though much more of a warrior than the US President.

In his own incoherent and naive flamboyance, Amin was preaching the song of greater equality in global terms. In his own simplicity and brutal responsiveness, Amin violated the canons of humanity in his own society. The domestic tyrant in Uganda was a voice of equity in world affairs. Amin was, quite simply, a case of heroic evil. The villain of domestic decay was a champion of international development. But what should constantly be borne in mind when dealing with the decay in Uganda is that the problem was not just Amin but a general normative collapse.

When the lights went out one night in New York city in the summer of 1977, a normative collapse occurred in sections of the population. There was greed and looting, wanton vandalism, reckless plunder, and sheer violence. A mere mechanical lapse in the supply of electricity let loose the demon of anarchy in America’s largest city.

In Uganda under Amin, the light went out and norms and values cultivated over generations came abruptly to an end. The nemesis of anarchy has its shadow over a society that once laughed and made merry. Now the tyrant is gone, the anarchy may still remain in Uganda for a while longer. It is because of these considerations that the world has found that it is not enough to destroy a tyrant.

The successful action against Amin must be now accompanied by a dedication to the reconstruction of the society which produced him. It is easy enough to preach human rights. It is far more difficult to practice human partnership. Uganda is one compelling test case for all concerned. This brings us back to the weaknesses and gaps of western approaches to human rights, on the one hand, and to the paradoxical moral stature of Idi Amin’s rebellion against dependency, on the other. Human rights cannot truly be divorced from the wider search for both political and economic equity. When Carter fell short of taking full account of the economic disparities between developed states and underprivileged societies, he weakened the moral basis of his crusade.

In contrast, when Amin became one of the persistent voices of anti-imperialism in the Third World, and played the role of demolition expert, he destroyed a substantial portion of the dependent structures that Uganda had inherited from colonialism. The brutal tyrant became a warrior of liberation.

To some extent, Third World tyrants are the illegitimate children of a marriage between domestic underdevelopment in their own societies and external exploitation by others. These bastards of an unholy matrimony are an indictment of both parents - the social fragility and weakness of will within the local society, on the one hand, and the social insensitivity and basic economic greed of the external suitors, on the other. To blame the brutal side of Idi Amin on the bastard alone, and not on the true structural parents also, is to be a-historic. To blame the rise of Amin only on the forces of imperialism outside is to betray an inner psychological dependency, and to seek constantly the comfort of blaming all one’s sins on some external Satan.

To blame the durability of Idi Amin only on the people of Uganda and their incapacity to resume control of their own destiny until helped by Tanzania, is to forget that the people of Uganda were not entirely free agents, not least because Amin obtained his weapons of destruction and repression from external sources, and received considerable degree of legitimacy from the international state system.

The tantrums of Idi Amin were due to the man himself, to the nature of Ugandan society in a historical perspective, and to the consequences of imperialism and the continuing external manipulation of Third World societies at large.

The ‘New International Moral Order’ requires therefore at least three levels of conscience: the conscience of the individual be that person ruler or subject; the conscience of each society, be that society powerful or weak; and the conscience of the world community as a whole.