Hope for sickle cell patients

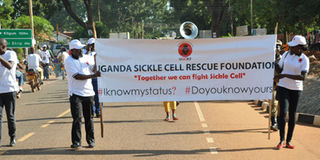

Members of Uganda Sickle Cell Rescue Foundation march through Gulu Town to mark World Sickle Cell Day recently. Photo by Beatrice Nakibuuka

What you need to know:

In the past, people used to treat sickle cell anaemia as a death sentence. Some would say children with sickle cells do not live beyond 12 years of age because of the recurrent fevers, painful swelling of the feet and hands, anaemia and several other complications that sometimes lead to disability. But today, there is hope for total recovery through bone marrow transplant.

Lukia Mulumba had lived a normal life until she went to hospital for blood tests two months into her first pregnancy. Mulumba was told she had a sickle cell gene. Now imagine her shock having been born in a family of 14 siblings who never had any symptoms of sickle cell.

“The doctor predicted that my child would have sickle cells because I had the gene. I was surprised because I did not know of anyone in my lineage with such a disorder,” Mulumba says.

Three days after she had given birth, she received her child’s medical results that proved she had sickle cell anaemia. “Throughout my pregnancy, I always prayed that my child would be free from sickle cell but the results showed she had it.”

Sickle cell anaemia is a group of inherited haemoglobin disorders that are a result of both parents having a sickle cell trait in their genes.

Mulumba, who is also the president and co-founder Uganda Sickle Cell Rescue Foundation (USCRF), says the news of having a child with sickle cells set her in an emotional turmoil.

“My daughter’s growing up was very difficult. She was always sickly. I had to spend more time in hospital than at home. There was even a time when I wanted to commit suicide because having a child with sickle cell can be too devastating,” she says.

Hope for a silver lining

Mulumba also recalls a time when she went to see another doctor for more tests on her child hoping that the diagnosis would change in vain.

“I had moved to the USA and did not know so many places there but I used to run from street to street to see a different doctor each time to see if he would give me different results. I did not like the idea of people calling my child a ‘sickler’ even if it was true,” she says. “When my daughter started school, her teacher would call me almost everyday to pick her because she was unwell. Her eyes were swollen, she had a headache and fever most of the time and would sometimes get strokes.”

Mulumba breaks down and cries when she recalls the time her daughter would take morphine drugs daily and the doctor had said her kidneys were not functioning well and she would be put on dialysis.

Despite the stress associated with raising her daughter, four years later Mulumba got pregnant and the doctors advised her to terminate the pregnancy because they thought the child would also have sickle cells.

Even if the pregnancy was unexpected, Mulumba was unwilling to terminate it because she had hope that her child would be born free of the sickle cell gene. Her prayer was answered and her son had no sickle cell.

The challenge with raising children with sickle cells has always been that the fathers leave the responsibility to the mothers and usually blame them for bringing the disorder yet the gene is sometimes carried by both parents.

Luckily for Mulumba her husband gave his full support especially in taking care of their daughter. And more luck came Mulumba’s way when her daughter had a free bone marrow donor in her young brother.

“She received two phases of the bone marrow transplant from her brother and 21 doses of chemotherapy and now she is leading a normal life.”

Mulumba’s daughter, Carol Mulumba was one of the first Ugandans to be cured of sickle cell disease through bone marrow transplant. She now has three children 15, 11 and seven years old all without sickle cells.

According to Prof Christopher Ndugwa, a paediatric consultant and board member of the USCRF, sickle cell disease is curable through bone marrow transplant. Prof Ndugwa, however, says that even without a transplant, a child can lead a normal life if they have early diagnosis and go for regular hospital assessments every three months even when they are not sick.

“In Uganda, there is need for a dedicated sickle cell clinic in most of the hospitals especially in places where the disease has been found to be more prevalent,” he says.

Move in the right direction

Recent statistics from the Ministry of Health show that the gene is higher in people living in the northern part of Uganda.

The prevalence of sickle cell in the mid north sub-region is 21 per cent followed by the mid-eastern sub-region with 16.5 per cent and central with 14.6 per cent. The national average of sickle cell in Uganda is 13.5 per cent of the total population.

On June 19, Uganda joined the rest of the world to commemorate World Sickle Cell day under the theme “Sickle cell a concern for all” in celebrations held in Gulu Town. There was a sickle cell awareness walk through Gulu Town and free screening and medication for people living with sickle cell disease.

According to the executive director USCRF, Sharif Tusuubira, the foundation has raised awareness about sickle cells in several communities.

They have organised free screening and testing for the haemoglobin disorders, offered psychosocial support through community sickle cell support networks as well as family economic empowerment for poverty alleviation.

Doctor cautions

Prof Ndugwa says untreated sickle cell disease can lead to death, problems with the hip joint that causes limping (this can only be corrected by a prosthetic replacement of the hip joint) as well as leg ulcers that do not heal easily. “It is important that before a couple gets married, they should go for sickle cell screening to ensure they both do not have a sickle cell gene. The disease is not contagious as some people think, it is not witchcraft.”