Giving hope to prisoners through education

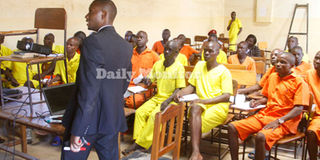

Richard Tumusiime teaching the ICT class at Luzira Upper Prison. Photo by ABUBAKER LUBOWA

What you need to know:

Light at the end tunnel. Getting jailed is one thing and living in the cells for a long time while getting an education is another. Gillian Nantume visited Luzira Upper Prison and interacted with student inmates.

A mute motivational video is projected on the wall. With mechanical concentration, students stare at the slides, silently reading the words.

We are in the University Hall of Luzira Upper Prison to attend an ICT lecture. The class has five computers sitting idle at the front.

You have to pass through four gates to enter the Boma Section of Upper Prison, and after the third gate, Ocom, my guide, told me I was the only woman there. No female warders are allowed in.

This is a first year class in a certificate course, and today we are learning what columns and rows in Microsoft Excel are.

“On my first day, I was not sure what to expect,” Richard Tumusiime, the lecturer from the Business Computing Department of Makerere University Business School (MUBS), says, adding, “My colleagues did not want to lecture here. The environment is different from the one at MUBS. However, I love helping the disadvantaged.”

Tumusiime always starts his classes with a motivational video or quote. “Those who enrol are self-driven and very attentive. In contrast, at MUBS, students are distracted by their smartphones.”

Inmate beneficiaries

Education is free, and only those with a hunger are attracted to it. Sowedi Mukasa was on death row until four years ago. During that time, he was the headmaster of the secondary school, studied certificate and diploma courses in Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, and represented himself in court.

“When I was arrested, I was remanded in Katojo Prison in Fort Portal District for two years,” Mukasa says. “With my fellow inmates, I started a school to teach inmates how to read and write.”

When he was sentenced to death, the Senior Six dropout was transferred to the Condemned Section, where he found an established school. Within two and a half weeks, Mukasa was appointed headmaster by the officer-in-charge (OC).

“In 2008 because of the number of candidates completing Senior Six, together with our partners we lobbied tertiary institutions to provide us with education.”

David Okiring, a senior welfare officer in charge of rehabilitation, says, “You cannot keep people serving long sentences idle. Our records show that repeat-offending is caused by illiteracy. Some inmates did not want to do carpentry so we started the education programme. We got in touch with a number of universities but only MUBS bought the idea providing tailor-made courses in Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management at certificate and diploma levels.” Currently, the certificate course has 33 inmates, while the diploma course had 54. MUBS courses are only offered at the Upper Prison. None is offered in the Women’s Prison.

Using education to better themselves

In 2009 and 2011, Sowedi Mukasa was a pioneer student in the certificate and diploma courses, respectively. “I was a victim of a miscarriage of justice and because my lawyer was inefficient, I spent 12 years on death row.” In his appeal, the former child soldier requested the Chief Justice for permission to represent himself, and consent was given.

“I read the Penal Code Act and made a write-up with the guidance of fellow inmates. When I made my submissions, the Chief Justice told me to refine it. Later, my sentence was re-heard in the High Court and the death sentence was quashed.”

In 2012, Mukasa began a 33-year custodial sentence. He was transferred to Boma Section and relinquished his position as headmaster though he still teaches. He is now a first year student of Common Law at the University of London, with six more years in prison.

“In 2009, I enrolled for Senior Six. Afterwards, I studied a diploma in Theology, and then joined MUBS for a certificate course.”

While studying the certificate course, he enrolled at the University of London for a diploma in Common Law. He graduated in 2013 and immediately decided to upgrade his certificate to a diploma. Currently, he is in his first year doing a Bachelors in Common Law. He is also a member of the Inmates Human Rights Committee.

“In 2013, I prepared my grounds for litigation, with my lawyer, and my death sentence was mitigated. I’m helping other inmates to prepare their appeals and to ensure their human rights are upheld.”

He also teaches Economics and Divinity at A- Level. He still has four years of his sentence to serve.

“If I am released I intend to enroll at the Law Development Centre or study a postgraduate in Human Rights.”

Picking an interest in law courses

Few years ago, the University of London provided an opportunity for inmates to study for a diploma and Bachelors in Common Law, sponsored by African Prisons Project.

“Some prisoners feel they are innocent,” Okiring says, adding, “Accessing legal services is expensive, so if we can expose them to legal knowledge to represent themselves and help others, it is a good thing.” There are three inmates in third year – one woman and two men on death row; and 11 first year students.

Anticipated life outside Luzira

Both Mukasa and Kakuru intend to practice law.

“Many former convicts are doing well,” Mukasa says, adding, “So, people should learn to forgive us and forget.”

Kakuru says everybody is a potential prisoner. “Some are here on circumstantial evidence, but with such educational programmes, we can add value to ourselves and remain focused.”

Vocational education – carpentry section

Not everyone in upper prison values education. The fourth gate in upper prison opens into the football pitch of Boma A recreation ground. A sea of men in yellow is all you can see.

Some are washing clothes, others playing, while the majority seat on verandahs. Beyond the high wall on the right is the Condemned Section.

We walk across the pitch and enter the noisy carpentry section, run by Barnabas Munyos. Some carpenters are sanding, some are sewing chair covers, while others are engaged in joinery.

“We only take convicts serving five years and above.It takes a novice three months to learn how to handle timber,” Munyos says.

The finished products are displayed at Lugogo Showgrounds, and according to Munyos, government has introduced a system where the inmates earn a small percentage of the sales.

Independence Kajarugokwe, a farmer, is serving a 20-year sentence. I found him applying white paste to a wooden tray.

“When I came here in 2011; I knew nothing about carpentry and now, I’m an expert. I plan to become a carpenter when I’m released.”

Andrew Ddungu was a driver for 10 years but you cannot tell it by the way he expertly handles an industrial sewing machine.

“Once I was convicted, to avoid depression, I joined the workshop. I’m getting out in two years but I have not decided what profession I will stick with. An inmate can spend 10 years in this workshop but when he is released, he cannot get employed because people still think he is a criminal. However, if he has startup capital he can open a workshop.”

Some inmates in the workshop are just refining their skills, such as David Okello who makes sideboards, tables and chairs; and Alex Ola, a woodcarver, putting designs on church relics. Both want to open workshops when they leave prison.

Beehive, the tailoring section

To enter the tailoring section, one must go through Boma B recreation ground, which is busier, with some men gambling with a pack of cards.

Another gate is opened and we enter a serene compound. Inmate tailors sitting on the grass are having their lunch. Others have remained working in the large workshop.

“We make uniforms for prisoners and UPS officers countrywide and presidential and judicial flags,” says Maxwell Ogwal Opio, who heads the section, adding, “We have 104 inmates working here.”

Francis Bwalatum, an instructor, says the tailors can make anything but it is done on a private basis, through the administration.

“My wife may bring her material for me to make a gomesi or school uniforms. The main thing is to master the skill.”

Bwalatum, serving a 100-year sentence, says the conditions in the tailoring section are good.

“We are well catered for in terms of meals and medical care. The decision of whether vocational training helps a former inmate depends on the individual.”

The challenges

Much as Uganda Prisons Services is partnering with various institutions, the funds required are enormous.

“The education programme has not been formally catered for, so management has to source funds from other activities,” Okiring says.

Inmates need stationery and reference literature. Sometimes, 20 students have to share one reference textbook.

“The textbook available may not be the one recommended by the study guide,” Mukasa says, adding, “We study by guess work.”

Inmates also carry the psychological weight of abandonment by their families, and suffer depression.

“We are constantly thinking of our wives and children who have lost hope and this distracts us.”

Also, it is not easy to convince the public that rehabilitated former inmates are useful to society.

“We are good people and we are receiving quality education. Some districts never have first grades in O-Level yet we get four or five in Upper Prison.”

Testimony

I was in the Mobile Police Patrol Unit when I was arrested in March 1993 and remanded to Maluku Prison. I was condemned to die in January 1995 and transferred to Upper Prison. I spent 15 years there.

I found inmates in the Condemned Section thinking of ways to fight the death penalty led by Chris Rwakasisi and Africa Gabula (both recently released). They decided to start a school from Primary One to Four.

John Kagambo, senior welfare and rehabilitation officer, said we should just wait for death but we appealed to Commissioner Joseph Etima who gave us a go ahead.

As a Senior Four dropout I became headmaster in 1997 until 1999 when I became chief ward leader. I taught Mathematics and English. In 2000, we registered the school for Primary Leaving Examinations.

We performed better than those in Boma and started a secondary school for the condemned. There were no teachers or textbooks but our best Senior Six student scored 12 points.

Many people died in prison and in 1996, three inmates were executed, while in 1999, there was a mass execution of 28 men. After every execution, classes would be empty for a week. You couldn’t convince someone who had seen a bright student die, to return to class.

Worry about what was happening to their wives and property overwhelmed some prisoners. They would isolate themselves and later run mad. Next thing you heard, they were in Ward 13, then Murchison Bay, and finally Butabika hospital.

I survived 22 years without falling sick because I knew I would get out. I never lost hope in God and direction.

Leaving death row

We took the government to the Constitutional Court in 2006. In the end, it was ruled that whoever had spent more than three years on death row should not be executed.

I was transferred to Boma to serve a 20-year- sentence without remission. Since I had already done 15 years, I had five left.

I enrolled for a certificate from MUBS and later, a diploma. When you are coming to the conclusion of your sentence that is when you think about a soft landing. With six months left, I wrote to Prof Waswa Balunywa.

When he came to Upper Prison, he asked me to go to his office after I had completed my sentence. I left prison in January 2015 and eventually got the job. I intend to enrol for an undergraduate degree. Willis Okello, Office Assistant, Office of the Principal, MUBS