What transpired during the referendum on lost counties

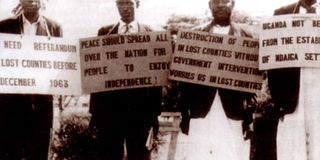

Men carry placards in support of a referendum to decide the fate of the two disputed counties of Buyaga and Bugangaizi in 1963. As Bunyoro celebrated victory in the referendum, the Baganda reacted to the loss with widespread riots. File photo

What you need to know:

Golden Jubilee. Tuesday this week will mark exactly 50 years since the referendum on the lost counties of Buyaga and Bugangaizi was held. Buganda’s loss of the said territory despite the £30,000 investment to ensure they retain the two counties was the beginning of the bad blood between Mengo and the central government, culminating in the 1966 crisis, writes Henry Lubega

It had been decided during the Lancaster Conference of 1962 that two years after Uganda’s independence a referendum would be held to decide the fate of the two disputed counties of Buyaga and Bugangaizi. The two were part of the six counties which had been annexed by Buganda Kingdom from Bunyoro Kingdom. The others were Buwekula, Singo, Bulemezi and Bugerere.

As he presented the Bill on August 25, 1964, Justice minister Cuthbert Obwagor said: “This House in accordance with provisions of paragraph (a) of sub-section (1) of section 26 of the Uganda independence order in council 1962 do hereby appoint the 4th day of November 1964 the date on which the referendum to ascertain the wishes of the inhabitants of the counties of Buyaga and Bugangaizi as to the territory in which each of the two counties should be included, shall take place.”

After the presentation, some Kabaka Yekka (KY) party members walked out of the House, but the Bill was supported by members from both sides of the House, including some KY members who stayed.

Paulo Muwanga, a Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) backbencher, told those walking out that the remedy for any aggrieved members was to go to court. Adding to his voice was KY’s secretary general Eriabu Lwebuga who supported the Bill because the Buganda team at the Lancaster conference in 1962 had accepted to have the referendum two years after independence.

“Although the delegation walked out of the conference, whenever the colonial secretary raised the issue of the lost counties, they accepted clause (26) of the constitution which provided for the referendum,” Lwebuga said.

During the second and last reading of the Bill, the Justice minister said: “The referendum was in accordance with the Uganda independence order in council of 1962 and was necessary because a solution could not be reached at the independence conference in London.”

The Bill provided that only those registered to vote in the counties in 1962 would be eligible to vote. This provision automatically excluded the Baganda ex-servicemen who had been settled in the two counties by the Buganda administration under the Ndaiga Scheme, which started in 1963 with the intention of boosting the Baganda numbers to influence the results of the referendum.

Once passed, the Bill could not become law unless it had been signed by the president, in this case who was Sir Edward Mutesa, who was also the king of Buganda. This put Mutesa in a tricky position. Presented with the Bill for signing at the State lodge in Makindye, he asked for some time, saying “these are difficult days, I have to consult one or two persons”.

With the president not signing the Bill, legal steps were taken to have the Bill signed into law by the prime minister.

Legal Action

Soon after it’s becoming law, courtesy of prime minister Milton Obote, the Mengo government together with a one Petero Kabuye of Kyakanena village in Buyaga County who was represented by John Kazoora, took the central government to court, challenging the validity of the referendum. They challenged the Act which the prime minister had signed into law in September.

The Bill also disenfranchised close to 4,000 ex-service men who had been relocated to Kyakanena under the controversial Ndaiga project, including Kabuye who had moved to the village after the 1962 elections.

Appearing before a panel of three judges made up of Chief Justice Udo Udoma, Justice Jones and Justice Sheridan, Attorney General Godfrey Binaisa QC said:

“Until the voters’ register is revised, the register used in the 1962 general elections stands and should be the one used in the referendum. Otherwise if everybody was allowed to vote there would be chaos and havoc in the area.”

The plaintiff’s counsel Kazoora and J.G. Quesh QC argued that any Ugandan in the area for the past six months and was 21 years and above was eligible to vote.

In his ruling on October 30, 1964, Chief Justice Udomo said the Mengo government and ex-serviceman Kabuye failed to convince court on the grounds that the referendum was unconstitutional and invalid.

However, the Mengo government was dissatisfied and appealed against the High Court ruling and the case was referred to the Privy Council in London, which also ruled against the complainant.

The voting

The two counties were divided into 72 polling stations, with the ballot paper having three questions, to remain as part of Buganda, to go back to Bunyoro or to become an independent district under the central government.

After the counting of the votes in Bugangaizi, 2,253 had voted in favour of remaining in Buganda, 3,275 had voted in favour of going back to Bunyoro, with 62 voters preferred the formation of a new district.

In Buyaga 1,289 wanted to stay in Buganda, 8,327 preferred going back to Bunyoro while 50 voted for the creation of a new district.

The aftermath

As Bunyoro celebrated its victory, in Buganda the loss was greeted with widespread riots. The Katikkiro of Buganda, Michael Kintu, was threatened with death on allegations that he had betrayed Buganda and sold them to Bunyoro and the central government.

The discontent in Buganda and within the Mengo establishment was not restricted to the loss alone, but also on how the £30,000 was spent on the Ndaiga project to secure the two counties.

As tempers flared, a kingdom official issued a statement saying the two counties were still part of Buganda as the kingdom did not recognise the Act under which the referendum had been held, and it even had a pending appeal in the Privy Council in London.

However, Mulindwa Nsi Eribetya a Lukiiko member representing Makerere, accused Katikkiro Kintu of feeding the Baganda with lies.

People such as Kabali Masembe, a kingdom official at the time, sided with the people in demanding for the resignation of the Katikkiro and his entire cabinet. Four days after Bunyoro’s victory, Kintu and his team bowed to the pressure and resigned. The resignation statement read by justice minister E. D. Lubowa stated: “The cabinet has realised the seriousness of the matter and has decided to resign.”

Obote’s response

After the referendum, Milton Obote as the executive minister addressed parliament on November 6, 1964, saying: “Members of the public who live in Buganda must know that the president of Uganda who swore to uphold, preserve and defend the constitution of Uganda is also the Kabaka of Buganda and that all matters affecting the Kabakaship are the responsibility of the Lukiiko.”

“The Lukiiko last year had the responsibility to advise the Kakaba before assuming the office of the president as to what oath he should take. No representation came to me as prime minister from the Lukiiko that the Lukiiko would not agree to the Kabaka as president taking an oath which would bid him to respect each and every provision of the constitution of Uganda, including section 26 of the order in council which provides for the holding of the referendum in the counties of Buyaga and Bugangaizi.”

About the 1966 crisis

On May 24, 1966, government soldiers, commanded by Idi Amin, marched on the Buganda Kingdom palace at Mengo.

The attack, ostensibly carried out on the orders of Apollo Milton Obote, saw century-old treasures and royal regalia of Buganda Kingdom reduced to ashes.

The soldiers were also accused of killing thousands of defenceless civilians, carrying out lootings, rapes and torture.

Scores of kingdom royalists and loyalists were arrested and jailed without trial as Obote, using recently-acquired executive powers of the presidency, declared a state-of-emergency in Buganda.

As smoke rose over the Lubiri Palace, so did hatred for Obote among the Baganda.

The greater impact of that attack is the injury it would cause to the pride and reverence the kingdom wielded in Uganda.