20 years after the inferno at Kanungu

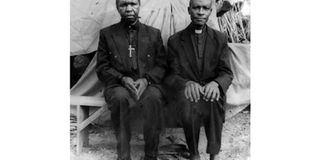

Joseph Kibwetere and Rev. Fr. Dominic Kataribabo. Courtesy Photo

What you need to know:

- Doom. Tuesday, March 17 will mark 20 years since followers of the Movement for the Restoration of the 10 Commandments met their ‘judgment day’. Like Prophet Elijah, the faithful of Nyabugoto looked forward to being carried into heaven in chariots by the Blessed Virgin Mary, as the rest of the world faced its doom. It’s them that faced doom.

As clouds in the sky began to gather, I increase my pace. The cocktail blue shade of clouds was becoming darker, forming into gravel-grey large pillows discolouring the sun into an old gold. In a blink it had started raining.

I was just halfway to a dilapidated house managed by Teles Rwengabo when I got splattered.

Eventually, the rain subsides and the silver trickles of water seeped into the soil. The sun comes out again, shading more light on the beauty that is Kanungu. I later find my way through the sparsely populated town to Rwengabo’s.

Seated at an old verandah of his detached room he has patiently waited for my arrival.

“You are welcome,” he murmurs with a feeble voice as he gave me a handshake. His old body seemed slightly inflamed from cold.

He then led the way to what he referred to as his office.

An old place it is, the floor has lost much of the cement and so did the walls, the bricks are visible. From within, an old bookshelf and tables lay stagnant, dusty, but holding a weight of many tattered documents and books. The dingy brick walls are streaked by the drippings from the leaky roof.

Among the many books lays the title The Kanungu Massacre, an investigative report that was compiled by the Uganda Human Rights Commission months after the inferno.

The doomsday

Taking hold of the book, the 82 year-old recalls the tragedy in Nyabugoto on March 17, 2000 like it was yesterday.

“It was between 9am and 10 am when I heard a blast. Running out of my office I stood by the roadside. From a distance, I could see a thick gray smoke billowing into the skies. The blue sky was now shielded by a veil of darkness as smoke swallowed up the whole camp at Nyabugoto. Fierce fire was seen sneaking out from the rows of trees that stood high at the top of the hill,” Rwengabo narrates.

He talks of screaming and shrilling cries of agony that tore through the entire Kinkizi County.

It was the kind of screaming that he says made his blood run cold and body trembling. Wondering what was happening, he heard a voice yelling from the far ends of the valley, it was his friend, Mzee Katwigi shouting at the top of his voice.

“Baasya, baasya, baasya ”( Kiga for; they have burnt, they have burnt, oh, they have burnt) he recalls.

“It was not long before the news got to everyone’s ears. One by one the residents stated lurching their way through the hills to the camp. But by the time many of us got there, it was too late. Friends, mothers, fathers and children had perished beyond recognition.”

The victims

Thirty-two-year-old Jovalyne Nankunda can’t stop imagining the struggle her aunt Veronica Busingye might have gone through at the time the church was set ablaze.

To date the memory of the fateful day still plays like a song in her head and a mere thought of it reopens emotional wounds.

She curses the day her aunt decided to join the sect. The day she says denied Busingye and the rest a decent burial.

“I was about 12 years when everything happened,” she says.

Years before, she was staying in Bwambara, Rukugiri District with her aunt when a group of people she had not known started frequenting their home.

“They would spend hours talking and praying with my aunt.”

However, after a number of visits, Busingye told them she was leaving her marital home to start staying at the camp in Nyabugoto, Kanungu.

Nankunda watched the once happy family torn apart. Her aunt’s hapless husband looked on as his wife Busingye was being taken away by the cult leaders.

“The day aunt left for the camp, a white car parked in our compound and all her property was loaded on it. However, her clothes were burnt and a red cloth was handed to her.”

From that time Nankunda claims not to have seen her aunt again, untill the day she came over to invite them to a party that was to be held at camp. Little did she know it was the last time they were going to hear from each other.

To Nankunda, what hurts most, is the fact that there is no grave in Nyabugoto site that can be identified.

“The remains of those that got burnt were buried in mass graves, but today, there is nothing to prove the graves exist. There is nothing like a memorial tab for the next generation and for those who lost relatives,” she laments.

Nankunda reveals that Busingye died with nine other family members who had gone to attend the party. They included three of her children, two daughters-in-law and three grandchildren.

The last days of the sect

Godfrey Tumwebaze Karabenda who at the time of the tragedy served as a district councillor representing Kirima Sub-county where the cult was located revealed that from March 14 to 17 the road to Nyabugoto seemed to be under endless waves of shoes that walked up and down the camp.

“In the last days people from different parts of the country kept flooding Nyabugoto. A number of invites for the party that was scheduled for March 17 were sent out to different people,” he states. Reflecting on an account of events that happened before the sect’s ‘last supper.’

Give Caesar what belongs to Caesar….

On the morning of March 15, 2000 Karabenda, who is now the serving mayor of Kanungu Town Council, claims to have seen Kagangura (the cult’s farm manager) and Ursula Komuhangi visit Kirima Headquarters. While there, Komuhangi paid graduated tax for all the adult male followers in the sect.

“Nua Muhwezi, the then sub- county cashier was overwhelmed. I remember him asking Komuhangi to let him complete the registration the next day. An idea Komuhangi agreed to.”

On the morning of March 16, Karangwa (not certain of the other name) went to Katata Police Post to handover the cult’s documents.

In so doing he claimed the documents were safe in the police’s custody for the camp was expecting a big number of visitors. These included a land title, articles of association and certificate of incorporation.

“The cult owned a shop in Kanungu which dealt in hand crafts and sold booklets with their preaching. However, days to the party, the booklets were given out freely,’ Rwengabo shares, turning pages of a booklet that was owned by the sect titled Obutumwa Bwaruga Omu Eiguru.

Working close to the sect

Nalongo Rukanyangira was a childhood friend of Sister Credonia Mweride, and she worked closely with the sect that the doors to her house were always open to her old friend

“After a long time without seeing each other, Mwerinde returned, but this time dressed like a nun. People around her referred to her as Sr. Credonia something I found awkward because this person had once worked as a prostitute. She had two children with two different men,” she expressed.

Minding less of who Mweride had become and what her intentions were, Nalongo welcomed her old friend with open arms.

Andrew Baguma shows part of the remainings of what used to be the camp site for the religious sect. Photo by Phiona Nassanga

“Much as I did not believe in her preaching, I could not refuse business from her. My husband and I owned a pick-up, number plate UXO 00I and on many occasions she hired us to transport members of the sect from one camp to another.”

Nalongo says most of the time these people were transported in the night though this never bothered her since the pay was good and timely.

Kibwetere and the mystery

If there was one name that was outstanding in all reports about the inferno, it was Joseph Kibwetere. Recognised as the leader of the movement, he is said to have been well-read and connected.

Nalongo says Kibwetere helped in recruiting a number of people thanks to his connections: “People think that all those that died were peasants from the area, some were respectable people who had been brought in by Kibwetere.”

In the 1980s, it is said the man had given a shot at politics but things probably did not work out. He had also offered a piece of land for a school of his own design to be set up.

Because of such acts, his reputation in the communities of Kanungu was positive.

Some writings though note that at the same time, he claimed to have experienced sightings of the Virgin Mary.

Meanwhile, elsewhere Mwerinde too had been claiming to see the Virgin Mary after looking at a stone in the mountains. But visions were not new in Mwerinde’s family, her father for instance had claimed visions of his dead daughter as early as the 1960s.

In 1989, while preaching, Mwerinde and Ursala Komuhangi met Kibwetere who shared his own experiences of the Virgin Mary and that’s how the movement came to be.

Another account though claims the Virgin Mary had allegedly directed Mwerinde to Kibwetere or, Mwerinde chose to work with him aware of his reputation in the community.

Kibwetere came to be known as the leader of the cult, though, In an earlier interview, Paul Ikazire, one of the sect leaders who later abandoned them and returned to the Catholic Church, says he was only a figurehead.

Nalongo too seems to believe this, she says most of the decisions were made by Mwerinde but she was happy to present Kibwetere as the head since he was a man and had been ordained Bishop, just like it is in the Catholic Church.

In 2014, police tabled a report about the inferno, it was said Kibwetere and those involved had escaped through Tanzania to Malawi. Nalongo says Kibwetere did not die in the fire, but may have died a year earlier.

“The last time I saw Kibwetere must have been around June 1999. At that time he was very sick,” she says.

“I was asked by Mwerinde to drive him to Bushenyi.”

Much as Nalongo continued transporting sect leaders to different places, even days to the incident on March 17, she says Kibwetere was not one of them.

To date, Kibwetere’s fate remains unclear, whether he died from the sickness Nalongo talks of or lived on, worked in the shadows and died with the group or escaped, it is all unknown.

On March 15 and 16, 2000, Nalongo reveals that she went shopping for the party with Mweride.

“We bought sodas and delivered invitation letters to different people. Meanwhile I was one of the people who were invited by Mweride, but had not arrived at the time of the blast.”

The faded memories

The pungent smell of burning human flesh that engulfed Nyabugoto is today long forgotten. The shrilling cries of the cult members in the inferno are now chapters of books left on the book shelves to gather dust.

Today, Nyabugoto hosts a tea estate and tracing where the dormitories and church once stood may be hard. The foundations have been eroded and the relics have vanished with time. Yet, even the few surviving witnesses have no evidence.

“During the investigations, by the Uganda Human Rights Commission the only photos I had of Mwerinde were taken and never returned,” Nalongo reveals.

Karabenda reveals that the 23.6 acres which were occupied by the sect are today owned by Benon Byaruhanga.

“The land in Nyabugoto belonged to Paul Kashaku who was father of Credenian Mwerinde. But in 2010 it was sold off by Alex Atuhurire and Mary Kyomugisha the biological children of Henry Byarugaba and John Begira, siblings of Mweride.”