Prime

Bob Astles is rejected by Kabaka, hangs onto Obote, Amin

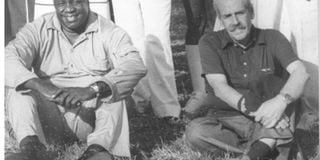

So much has been said and written about Maj Bob, as Bob Astles (R) came to be known during his close association with Idi Amin (L).

So much has been said and written about Maj Bob, as Bob Astles became to be known during his close association with Idi Amin, and most of it detrimental, that I find it hard to reconcile the public image with the man I knew.

To me, Bob Astles was an amiable eccentric. When a South African friend, Jessie Okondo, brought him to our house, having met him at the home of Princess Irene Ndagire, the impression was of a bluff middle-class Englishman.

He had a very trim beard and was conservatively dressed in tailored tweeds. He wasn’t very tall, but stockily built, and altogether looked something like old photographs of King Edward VII.

This first encounter must have taken place shortly after Independence, because the country’s independence seemed to produce a rash of divorces. Disregarding the scandalised traditional element in our society, wronged wives headed for the courts.

Rash of divorces

Jessie and I were among the first divorcees, and Princess Irene Ndagire was separated from her husband.

In Bob we found a true friend. He willingly chauffeured us about when we were stuck for transport, fixed tiresome things that went wrong in our houses, was always ready with advice and offers off assistance if we had problems, and was Uncle Bob to all our children.

He had a strong protective instinct towards us and anybody else whom he imagined was under threat in some form or another. This sometimes back-fired.

For instance, the managing director of an international soft drinks company hanged himself from the balcony of his Kololo villa, and everyone assumed it was because of acute depression or an overwhelming personal unhappiness: that is, until Bob Astles made the rounds of people known and unknown to the deceased, aggressively declaring that he had come to defend the dead man’s character. The Astles’ uncalled for defence set everybody wondering what there was to hide, and soon unsavoury rumours were rife.

At the time Bob was a road supervisor with the ministry of Works, and lived in a small bungalow with an interesting collection of wildlife and a dog.

Apparently, the first Ms Astles objected to a python’s regular presence on the warm tubes operating the fridge and had taken off for good.

I went to Bob’s house one afternoon, and there was an owl perched on the back of the sofa. He explained that it was recovering from a damaged wing, and said it was very placid.

The trouble was that the owl kept dozing, losing its balance and falling in a flurry of feathers and indignant hoots into the lap of whoever was sitting on the sofa. It was most unnerving for visitors, and no use trying to find another seat, since Bob did not believe in cluttering up his home with too many chairs. As dusk fell, a mongoose scuttled across the room, and a bushbaby suddenly appeared to swing on the curtains.

The servants’ quarters were taken up by young Crested Cranes which Bob exported to overseas zoos. I never liked the idea, and told him so. Not that it made any difference. His monkey was a different matter altogether.

He would probably have had to pay a zoo to take that creature off his hands. It had much in common with Ms Daly’s Nefertiti.

It was on a long chain attached to a tree in the front garden, and used to screech and jibber whenever it caught sight of a woman or a child.

From a safe distance I’ve seen it play a friendly game of football with Bob and his dog, but it remained unpredictable, and not even Bob would rely on the monkey’s goodwill.

He was having a bath one day when the animal broke loose from its chain, got into the pantry attached to the kitchen and created havoc with everything on the shelves. Then it grabbed a bag of dog biscuits and pelted Bob with them through the open bathroom window.

Bob was at his best with children of all ages. He occasionally gave Sunday curry lunches, and the children ate first and together at a low rustic table in the garden. He also hung a swing for them, and generally left the adults to fend for themselves while he entertained and photographed his younger guests.

At Christmas at our house, my sons always invited their pals on Christmas Eve to see the tree and eat a few mince pies, then for a slap-up tea on Christmas Day.

Apart from children like Freddie Mpanga’s twins, Grace Kato and Steven Waswa, and Jessie’s daughter, Catherine, many of them were homeless little boys who earned a few cents in Mengo market and slept under the stalls when they were not playing in our garden.

For the festivities, Aston, our servant, made a point of bathing them in an outside tub, and dressing them in whatever extras he found among Tofa and Daudi’s clothes.

Bob heard about the parties, and arrived one Christmas Eve with a film projector and a cartload of sweets. He gave a splendid film show of cartoons, but the hot favourite was a black and white movie about two mischievous bear cubs. Thanks to him, we all had a great time.

‘Never short of the stuff’

Then there was his boat and his island on Lake Victoria. He can’t have earned much money as a road works foreman, but he was never short of the stuff.

He owned the very best of camera equipment, as well as radio apparatus which enabled him to tune in to stations all over the world. The first I heard of his boat and island was when he offered to take me and the children on a trip.

We set off one Sunday afternoon from Port Bell, and the vessel, to my surprise, was large enough for us to move about comfortably on deck. When the island hove into sight, however, I looked at its uncompromising steep cliffs with dismay.

The children were quite small, and I didn’t see how they or I would make it to the top. Bob was unperturbed. He dropped anchor in the shallows, assisted everybody into a row-boat and deposited us on a very narrow stretch of sand.

The cliffs looked even more daunting as we stood below them, although they could not have been as high as I still imagine them, for we somehow climbed them, children and all, and arrived, hot and gasping, on the edge of a dense forest.

Bob led the way into it, through a tunnel of menacing thorns. Just as I began to wish that we had stayed out on the lake, he startled us by giving a series of penetrating whistles. In response, teenage boys, at least a dozen of them, sprang into view from holes in the ground and out of trees.

It was frightening till the boys gathered around Bob, grinning, and he commended them for putting on ‘a jolly good show’. I shall never know how or where he collected these youngsters, and according to him there were many more.

He claimed to have a regular arrangement to ship a number of them from Port Bell every Friday and leave them on the island till the following Sunday where they were supposed to practice self-sufficiency and commando tactics.

They carried food, but if the supply ran out before the weekend was over, they had to live off the land; and if they forgot to bring matches, they went without cooked meals.

As for the commando tactics, these, Bob seriously explained, were to turn the boys into the good combat unit which the Kabaka was certainly to need in the near future, judging from the way things were going.

True, the Kabaka’s differences with prime minister Obote were beginning to ripple the surface of our complacent lives, but open warfare? Never!

Strangely, while Bob professed to be a staunch royalist in those days, his only connection with Mengo seemed to be his friendship with Princess Irene Ndagire. He was never seen at the palace, and the Kabaka who had only heard of him, dismissed him as a crank.

Maybe this obvious lack of interest in Bob’s support and activities accounted for the dramatic change of heart after Obote did away with the presidency as it stood, and was on his way to re-writing the Constitution: soon after the announcement, Bob was to be seen on the steps of Parliament, loudly announcing to nobody in particular that it was time for King Freddie’s Kabaka Yekka and the Mengo set to be put against a wall and shot.

‘Out on a date’

But long before he called for the mass execution and continued to be welcome in our house, he once surprised me by formally asking me out for an evening: in other words, out on a date.

Expecting to be dined and wined at one of Kampala’s fashionable restaurants, I dressed accordingly, right down to the high-heeled silver sandals which made up in glamour for what they produced in pain. My expectations appeared not to be unfounded when Bob came for me looking quite debonair.

The only discordant note as we set off on our date was a very strong smell of fried fish inside his car. Nevertheless, my hopes of a wonderful evening soared as we bypassed the city and went along the Entebbe Road.

The Lake Victoria Hotel, Entebbe was our destination, or so I believed. As we turned off the main road and trundled down a track outside Entebbe township, I made another guess: a dinner dance at the Yacht Club. Well, things could be worse...... They were.

Another boulder-strewn track ended at the water’s edge. Bob stopped the car, rooted in the boot and came up with a large flat wooden case, a tripod and a telescope. Opening the case with a flourish, he invited me to admire what looked like hundreds of lenses to fit the telescope.

For the next hour-and a-half we peered at the moon and stars through nearly every one of those lenses. At the end of the exercise I was cross-eyed and in the grip of a massive headache.

Also, I was hungry. Bob agreed that it was time we ate, and produced two packages of lukewarm fish and chips, and a bottle of sweet sherry. We shared this dainty meal in the car while he lectured on the stars. I threw-up as soon as I reached home.

He never asked me for another date, and shortly after he went to live with somebody working for Save the Children. I only visited them once, and cannot honestly say the atmosphere in that house was anything other than miserable.

The woman looked down-trodden as well as unhappy, Bob openly treated her like an inefficient servant, and his sole interest was a new radio set-up on which he planned to teach his boys to be radio hams.

I don’t think that I ever saw or spoke to Bob again, but I heard enough about him to make me wonder whether or not he was going out of his mind.

I knew that he has switched from road works to television, which was not surprising, considering how effective he was with a camera, but then there were strange stories of his moving around with a posse of soldiers and ordering people’s arrest on trivial charges.

On one occasion it was rumoured that a bomb had been dropped on Arua in West Nile. I don’t know how true this was. Anyway, Bob was at Entebbe airport with his military gang when a civilian plane landed from Zaire, and Bob ordered the arrest of an Indian passenger who, he insisted, was responsible for the bombing of Arua.

And how did Bob know? Easy. As he told people drinking in Uganda Club that same evening, the Indian had been identified as the person who leaned out of a plane to drop the bomb.

He was probably more laughed at than feared during his stint as an Obote devotee. He was taken more seriously as soon as he became Maj Bob. Idi Amin’s right hand man.

There are people who lay at his door countless atrocities. Yet Felix Onama, a UPC adherent and somebody who held various ministerial posts under Obote, and who fled across the border to Sudan while the Amin reign of terror was in full sway, strongly maintain that Bob Astles was innocent of harming anybody.

Felix, who as far as I can see, gains nothing from standing up for Astles, insists that Bob helped many people and was a restraining influence on Amin. Many of the European community who remained throughout the troubles agree with him.

Having gone to work in Kenya before Bob hit the headlines worldwide, I am in no position to pass judgment. I can only think back on the man I knew and reflect on the unusual aspects of his personality.

I now see that Bob Astles was never a ‘man’s man’. He was comfortable with unprotected (as he considered them) women and children. He never had close male cronies with whom he could prop up a bar and natter endlessly about soccer, or get untidily drunk. It seems to me that he was more at home in trying to live a boy’s adventure story. Lord of the Flies would have more than adequately contained him.

Pictures of him humbled kneeling in the dock at his first appearance in a Kampala court as a ‘war criminal’ after the fall of Idi Amin, white haired and somehow shrunk, horrified me.

He was a man who tried to live out his fantasies, childish, though they were, and he needed to hitch his wagon to a star. The Kabaka rejected him, and so he hitched on to first Obote and then Idi Amin. I’m willing to bet that in both cases, Bob saw himself as a knight in shining armour, defending the honour of the current king.

ABOUT BOB ASTLES

Bob Astles was born in the UK in 1924. He joined the British Indian Army as a teenager and then the Royal Engineers, reaching the rank of Lieutenant.

In 1949, Astles was sent on special duties during the Bataka uprising in Buganda. His first job in Uganda was as a colonial officer with the Ministry of Works, then with £100 he set up Uganda Aviation Services Ltd, the first airline in Uganda to employ Africans.

As Uganda’s independence approached in 1962, Astles became involved with a number of political groups. One of these was led by Milton Obote, who led the country to independence. Astles worked in his government until the 1971 coup d’état, when he transferred his allegiance to Amin.

After Amin’s overthrow in 1979, Astles spent two years facing a death sentence for murder, then four more in jail after his acquittal before being deported, having renounced his Ugandan citizenship. He died in December 2012.