Prime

How Kabaka Yekka, UPC marriage was hatched

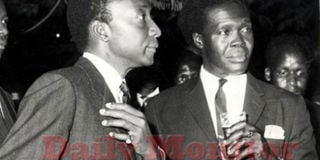

Kabaka Mutesa (L) and former prime minister Milton Obote at a public function in the 1960s. Obote’s UPC formed an alliance with Kabaka Yekka, the political party of Buganda, to gain a majority in the 1962 general election. FILE PHOTO

Immediately before full independence, on March 1, 1962, there was self-government, and the Democratic Party (DP), led by Ben Kiwanuka, had the majority after the parliamentary elections.

Kiwanuka, who automatically became prime minister, was a shrewd lawyer possessing a dry sense of humour as well as a beautiful wife, Maxi, and numerous children.

The Democratic Party had the backing of the Roman Catholic Church: indeed, Kiwanuka and Maxi had special prie dieus [a piece of furniture for use during prayer] at the front of Rubaga Cathedral, and priests did not hesitate to tell congregations to vote DP. In some cases they made it sound like a mortal sin not to.

One particular monsignor, a Muganda, up at Rubaga Cathedral, an absolutely beautiful man whose black, red buttoned and sashed cassock seemed to be designed for him alone, went a bit too far in exhorting his flock to forget traditional ties with the Kabakaship and henceforth concentrate on the Democratic Party.

Before he realised what was happening, he was escorted by Kabaka’s askaris to the palace to explain himself.

The Kabaka was sufficiently annoyed that his subjects were more or less being advised to ignore him, but when the monsignor grandly announced that nobody had jurisdiction over him because he was a prince of Rome, Mutesa lost all sense of diplomacy and had the man carted off to the Omukula we Kibuga’s office.

As soon as word passed of the arrest, Catholics converged on the cathedral, weeping and wailing and tearing their hair.

Meanwhile, the monsignor was receiving tea and courtesy from the Omukula we Kibuga who frankly did not know what to do with him. Nobody was more relieved than the Omukula when a message arrived from the palace to the effect that that tiresome priest was to be released immediately.

I went up to Rubaga that evening out of curiosity. The monsignor was walking up and down the upper terrace, smiling in a saintly fashion and pausing every other step for yet another sympathiser from the milling crowd to kiss his hand.

From the way he and his supporters behaved, anyone might have thought he had just evaded the lions in the Coliseum.

I relate this little story for very good reason: last time I was home in Uganda, I walked along Kampala Road and there on the opposite pavement was this smarmy monsignor with a group of people, the same saintly smile pinned to his face.

My companion and neighbour, Chris Mulumba, a man about the same age as my sons and therefore only able to go on hearsay and legend, reverently pointed out the priest as the someone who had defied Mutesa II and been imprisoned under torture.

For this reason alone, everybody had been surprised when he did not succeed Archbishop Joseph Kiwanuka as Cardinal of Uganda.

My only comment is that despite its many faults, the church is never slow in spotting a fraud. Cardinal Emmanuel Nsubuga, who succeeded the well-loved Kiwanuka, was never prominent in the popularity stakes.

While he was an ordinary White Father, he once threw me out of the cathedral because my two dogs followed me inside during mass - but he did more for the poor and disabled than was thought possible during the turbulent and destructive eras of Obote and Amin.

No sooner were the DP in power, however, than up sprang Kabaka Yekka, a movement intent upon retaining the Kabaka’s superior position over any and everybody on Buganda soil: which since the Parliament buildings and government offices were in Buganda, made difficulties for someone heading the State of Uganda as a whole.

Translated, Kabaka Yekka means Kabaka Alone or Only, and it became a common greeting: e.g. one person called out ‘Kabaka!’, and the other responded with ‘Yekka!’, and both stuck a forefinger in the air.

This greeting became so common that once when His Highness had been to play squash with an Asian family on Kololo Hill, and he and I were sitting in George Malo’s car waiting for lights to change on a main road, a couple of people shouted ‘Kabaka’ through the car window, and the Kabaka absently replied ‘Yekka ‘, casually raising the obligatory finger.

Kabaka Yekka developed into the political party of Buganda with the blessing of the government and great Lukiiko.

As general election for the national government which would be in power at the time of independence approached, Mengo was in the mood to do anything to remove the Democratic Party and Ben Kiwanuka.

Ben had been guilty of a flippant remark, “I’ll go up to Mengo and see what’s bothering him,’ in reply to a reporter asking how he intended to deal with the Kabaka’s insistence on special status for Buganda in an independent Uganda.

From then on, his name was mud at the palace. So when Milton Obote, leader of the Uganda Peoples Congress, made overtures towards a liaison between his party and Kabaka Yekka to gain a majority in the coming elections, the Kabaka Yekka top shots thought they had made it.

I had met Obote casually over the years, the first time when he and his wife of the time went with Abu Mayanja and me to see the South African musical ‘Golden City Dixies’ and later when Abu, purporting to be a nationalist, was trying to whip up support all over the country for the various political parties they started before the UPC took off, and Obote asserting that Abu would be Uganda’s first prime minister. He never entered anybody’s head that he already saw himself as Uganda’s president.

The machination of Mengo broke up this political partnership with a breath-taking degree of cunning.

Abu was a known firebrand long before he returned from Cambridge and being called to the bar in Britain. He had led a rebellion against something or other at King’s College Budo, the Kabaka’s alma mater, and had thrown a spanner in the works at Makerere University. Everybody seemed to have been thoroughly relieved when governor Cohen somehow got him away to Cambridge.

He came home with none of his energy diminished, however. He sprang into my life while I was still working in the ministry of Education. I can see him now, small, wiry, large eyes behind thick glasses which he had a habit jerking upwards as he talked, and a way of clenching his teeth and grimacing while he talked.

Clever and articulate, but ruining the effect by sometimes trying to sound audacious and only succeeding in being embarrassing: e.g. in his maiden speech as a Kabaka Yekka Member of Parliament, he couldn’t resist a reference to a maidenhead which disgusted some members and grossly offended others.

His political activities before independence and before the disastrous speech were nevertheless productive, and they worried Mengo.

After all, he was a Muganda, and because what he had to say and what he wrote about Uganda as a united country was logical and persuasive, there was every danger, in the minds of the traditionalists, of his carrying along a vast section of Baganda society.

Many plots were hatched as to how to silence the heretic, but the chief plotters saw their big chance when Abu was invited to the United States of America to talk about the pre-independence situation in Uganda.

While he was gone, Kassim Male, the Kabaka’s government minister of education, died. His appointment had been motivated by the notion that it was time for a senior cabinet post to be the preserve of the Muslim community, in the same way that the Katikkiro was traditionally an Anglican, and the Omulamuzi (Chief Justice) a Roman Catholic.

To those at Mengo to whom Abu Mayanja was an irritating prodigal son, Kassim Male’s death was seen as the answer to their prayers: what better way of silencing the rebel than to offer him the ministry of Education and bring him back into the fold?

I don’t think that anybody who knew Abu believed he would accept. Apart from the Mengo plot to silence him being immediately recognisable for what it was to all and sundry, he was a dedicated nationalist and hardly likely to change his stand at the onset of independence: or so it was imagined.

What very few understood was the ease with which someone, anyone, can revert to type, given the right pressures.

Abu did not spring from a Baganda aristocracy, and beneath the intellectualism which gave him a high profile on the political scene was a traditional Muganda gratified to be recognised by the court at Mengo.

And it was surely the height of flattery to be summoned home from across the seas to play a leading role in his own king’s government, and that the summons should be backed by a personal message from Prince Badru Kakungulu, the Kabaka’s uncle and leader of the Sunni Muslims in Uganda.

When Abu returned from the United States, he had not yet replied to the offer of the ministry but the old guard at Mengo were not short on psychology.

A huge crowd was organised to give him a rousing welcome at the airport, and Prince Badru was there in person to embrace him and lead him ceremoniously to the open car which was all set to drive him to the palace.

Obote and several of his henchmen were also waiting to receive their political colleague, but Abu was barely given time to shake their hands before he was swept along to the cheers and ululating of the crowd.

Even from a distance, it was obvious that he was moving in a delighted daze. He had never before in his life had such a fuss made of him, and it was heady stuff. The private audience with the Kabaka and the cabinet of ministers must have sent him soaring with the clouds. From then on, the chances of his refusing the ministerial post were nil.

The next time I saw him was at his okwyanza in the new Bulange, wearing, rather awkwardly, a kanzu and busuti; and the excitement of the occasion caused his movements to be more nervously jerkier than ever.

It seemed at first that he was in the Kabaka’s government with the cautious blessing of Obote and the rest of the UPC hierarchy.

They, with equal caution, accepted Abu’s reasoning that he was in a position to further their cause and shape political opinion from within the Kabaka’s government.

They showed no surprise, however. When it was learnt how he was deliberately excluded from every important cabinet meeting and deprived of any political clout whatsoever. He was, in fact nearly driven mad with frustration, and everybody in his ministry was aware of it.

He might have been well advised to swallow his pride, drop the lot and go back to the UPC. Instead, he took to a pattern of behaviour more fitting to barbaric chief of the 19th Century than a minister in a government trying to present itself as moving with the times.

His sexual exploits were notorious. On one occasion, he attended a function, picked up a girl and took her in the car he was sharing with his brother and a driver.

He was getting down to business on the back seat when the girl’s boyfriend gave chase, drove Abu’s car off the road and, with the aid of friends, gave him and brother a good hiding. The most startling aspect of all is that afterwards Abu actually went to the nearest police station and tried to lay a charge of assault.

It wasn’t long before he was bragging about the number of children he had sired here, there and everywhere. It was almost as though his political frustration was vented in the contempt he showed for women, treating women as sex machines put on earth for man’s use. The only one he respected was his mother.

I remember him joining us one day when I was asked to show some British journalists over Lubiri. The journalists were keen to have his political opinions: Abu, with a sort of bitter relish, insisted upon describing the effect of worms on his many offsprings.

His bitterness in everything was understandable. As a member of the Kabaka’s cabinet of ministers, he had little option to becoming a member of Kabaka Yekka, which gained him the reputation of a turncoat, and when pre-independence conferences of districts and kingdoms were held up and down the country, he received a barrage of insults to this effect every time he stood up to speak.

I left out these embarrassing exchanges from the notes I was there to take for the Kabaka, but I know that they were gleefully reported to him by members of the Baganda delegation.

The same attitude greeted Abu later in the national assembly where he sat as a Kabaka Yekka member after the Kabaka Yekka/UPC alliance won the elections in the run up to full independence.

Abu remained in a political wilderness for years. Like so many others, he felt the brunt of Obote’s spite during the terrible years of the Obote presidency, and eventually taught in an up-country primary school.

He returned to active politics with President Museveni’s and the National Resistance Army’s takeover in 1986, and immediately became minister for Information.

His former friend and guru, Milton Obote oiled his way into Mengo as an unassuming chap more than willing to accommodate Baganda aspirations.

The Kabaka was pleasantly surprised to find him so agreeable. He made the big mistake of believing he was dealing with a gentleman, while the old guard flattered themselves that they had brought yet another politician to heel.

The trouble was that their form of politics was grossly out of date. The ancient art of palace intrigue was no match for a wily politician who had sprung from the soil.

By promising the Kabaka Yekka party that if they formed an alliance with the UPC and won the crucial elections, as they were almost certain to do, considering that Buganda comprised about one-third of the whole country, the Kabaka would be made President of Uganda, Obote was home and dry.

That such an arrangement was bound to increase the general animosity already directed at the Baganda’s presumption of superiority and claim for special treatment was regarded at Mengo as of no special regard.

William Wilberforce Nadiope, the then Kyabazinga of Busoga and a number of UPC hierarchy, indignantly let it be known that he too had been led to expect the presidency.

Nor was he shy about threatening dire reprisals against Obote if he, Nadiope was not installed in Government House, (to be called the State House after Independence) Entebbe, on the day of Independence.

The other hereditary kings were also annoyed, to put it mildly, when news of Obote’s machinations was leaked, but all was sweetness and light in the new love affair between Mengo and Obote.

We didn’t then know that we were dealing with the world’s greatest living liar.

Continues in Saturday Monitor next week.