Hundreds killed as residents rebel against Baganda agents’ rule in Kigezi

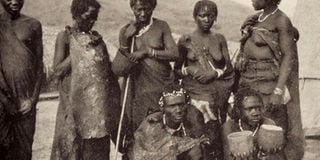

A group of Bakiga in the early 20th Century. Photo | gorillahighlands.com

What you need to know:

- History. The first Ganda administrative agent in Kigezi was Yoana Sebalijja, who established his post at Nyarushanje in 1910. Two years later, he went on to establish another one at Mparo, leaving Muganda agent Abdulla Mwanika at Nyarushanje. However, the relevancy of Baganda agents in Kigezi soon outlived its usefulness, writes Henry Lubega.

In August 1917, there was a rebellion in Nyakishenyi, then Kigezi District, against British rule.

The Bakiga residents were unhappy about the Baganda administrators whom the colonialists used to bring other kingdoms under their dominion. They accused the Ganda administrators of plundering their wealth.

Before the coming of foreigners in the area, a Mukiga prophet called Nyakairima prophesied that their land would be invaded by White men and that this would affect them significantly.

“Houses shall walk, ropes (roads) shall connect one corner of the earth to the other end. Your country shall be ravaged by men with White skin, and granaries will collide with one another. You will build with earth, you will thatch with earth,” Nyakairima allegedly said.

Administration of Kigezi

Unlike most places where the British found a centralised local administration, it was different among the Bakiga.

Writing in the 1909 Geographical Journal, Maj R.G.T. Bright of the Anglo-Congolese Boundary Commission said, “They have no chiefs, but managed their affairs by families.”

The role of a central administration was replaced by a spiritual being called Nyabingi which Bright described as “a cult of witchdoctresses” with great influence and was used to stir up strife.

According to The Sub-Imperialism of the Baganda by A.D. Roberts, the absence of any central administration made British adventure in the area difficult.

Instead, they turned to Baganda to help them bring Kigezi under their rule the way they did in eastern Uganda.

“With the lack of any suitable indigenous political organisation as an administrative foundation, coupled with the unfriendliness of the Bakiga, institutionalised in a spirit cult, it is perhaps not surprising that the British turned once again to the Baganda as agents of imperialism,” according to the 1962 edition of the Journal of African History.

Ganda imperialism in Kigezi

The first Ganda administrative agent in Kigezi was Yoana Sebalijja, who established his post at Nyarushanje in 1910.

Two years later, he went on to establish another one at Mparo, leaving Muganda agent Abdulla Mwanika at Nyarushanje.

For the first five years, the Ganda administrators were not under strict British supervision. To their masters, they were doing a wonderful job.

According to the 1916-1917 annual colonial report, “The actual management of the native administration machine is in the hands of the Baganda agents.”

However, the relevancy of Baganda agents in Kigezi soon outlived its usefulness. In 1920, the Kigezi District Commissioner, Capt J.E.T. Philips, highlighted the disadvantages of having Baganda agents.

“The district has been entirely in the hands of Baganda since its opening. The compulsory use of Luganda has been the most material influence in misleading the indigenous population. I cannot but consider its employment in this district to be a distinct political error,” Philips said.

“The local population has been submerged, incoherent and voiceless. Their attitude, needs and aspirations have only reached government, indirectly coloured by Baganda intermediaries who have perhaps unconsciously misrepresented.”

Though Phillips acknowledged the Ganda agent’s abilities, he was not blind to their shortcomings.

“Attribute is due to the intelligent and capable work performed by them, but their overbearing and domineering attitude to the local population has without a doubt been the direct cause of 90 per cent of the local rebellions in a country where European government has never been personally unpopular,” wrote Phillips in the Kigezi District Annual Report for the year 1919-1920.

An illustration of Nyakishenyi Sub-County agent Abdulla Muwanika hiding from the attackers. BY IVAN SENYONJO

Rebellion against Ganda domination

One Sunday morning in August 1917, a group of Bakiga men and women attacked the Nyakishenyi gombolola (sub-county headquarters).

They set fire to offices, huts of government employees and homesteads of Baganda during the attack.

The agent at the Nyakishenyi gombolola, Abdulla Muwanika, survived by hiding on the roof of his house.

Muwanika later turned into a key prosecution witness in the trial of Bakiga rebels.

“On August 12, I saw five hordes of Bakiga coming to my compound, shouting ‘we don’t want you here’. The Nyabingi has ordered us to kill you and drive you away,” Muwanika had said in his testimony.

The trial was presided over by J.M. McDougall, the acting District Commissioner (DC), and assisted by two Buganda assessors.

Muwanika narrated the death of his guard Kasimbazi, the wife of one of his servants only identified as Merajuma, and a young man in his compound called Malisa. They were all speared to death.

“Afterwards, at about 1:30pm, Kisaigala, a royal Mukiga chief, rescued us. He came with 40 people and they fought the rebels,” Muwanika told court.

Muwanika earned himself the nickname “Dirisa” because he escaped through the window when his house was attacked.

Another witness was Musa Wavamuno, a Muganda school teacher. He told court that, “After burning a number of houses, I heard some of the Bakiga crying out ‘we have come to pay tax’. But I saw no money in their hands, only spears and other weapons.”

“I went outside and saw Bakiga coming and shouting. They were blowing trumpets. I called Abdulla Muguluma and told him to run to the agent’s place. We went to Nakahima’s house. There were four men, three women and two children inside, all Baganda. We closed the door and the Bakiga set the front door on fire. We escaped through the behind door.”

In the end, 64 Baganda, 31 Banyaruguru, four Banyankore and one Muhororo were killed.

The other victims besides the Baganda were killed because they were friends with Baganda and had been allocated prime land in the area. Majority of those killed were women and children.

The colonial government lost the agent’s house, the lukiikko (parliament) building, five poll tax registers, case books for the court and five books of poll tax tickets. All were burnt.

Also destroyed were a Church Missionary Society church and a mosque. The European camp was spared the attack. The fact that the European camp was not attacked strengthen the belief that the Bakiga were not against the Europeans, but Baganda agents.

An illustration of attackers descending on Nyakishenyi Sub-county.

Learning of rebellion

Acting District Commissioner McDougall learnt of the Nyakishenyi attack through a note sent by Muwanika.

“I am telling you that the whole of my area has rebelled. They have killed many people. They have burnt my gombolola headquarters. We the survivors are besieged in my Kisakati,” the letter read in part.

On getting the information, McDougall sent two police officers accompanied by Dr Webb, a medical officer.

The DC left for Nyakishenyi the following day in the company of his assistant, E.E. Filleul. Unfortunately for the two, they got lost and reached Nyakishenyi two days later.

Retaliation

The rebellion by the Bakiga lasted a day. But the Baganda-led retaliation lasted five days.

In the five days of revenge, more than 1,000 rounds of ammunitions were expended, 479 heads of cattle, 764 sheep and goats were taken by the Baganda and distributed among themselves. This was compensation for the suffering they underwent at the hands of the rebels.

Writing in the Uganda Journal volume 32 of 1968, F.S.

Brazier says: “It is likely that the zeal of the Baganda in avenging the death of their fellows and the eagerness of all and sundry to pillage what they could must make the official figures an under-estimation.”

At the end of the fifth day, the number of causalities on the rebels’ side was put at 100, while 20 were taken prisoners.

Two of the rebellion leaders, Baguma and Bagologosa, fled to Rujumbura from where they were arrested and tried in Kabale.

They were charged with murder and sentenced to death. On February 27, 1918, they were hanged in Kabale near the roundabout.

The reaction of the British against the rebels did not deter some Bakiga in Nyakishenyi from becoming collaborators in later years.

Two of the first Bakiga chiefs from Kigezi came from Nyakishenyi and they were nephews of one of the leaders of the rebellion, Baguma.

Though the British did not openly condemn the Baganda for being responsible for the rebellion, Brazier writes, “The British looked into the Bakiga grievances by gradually involving the Bakiga in their own government by substituting Bakiga chiefs for Baganda.”

1917

Attack. One Sunday morning in August 1917, a group of Bakiga men and women attacked the Nyakishenyi gombolola (sub-county headquarters).

They set fire to offices, huts of government employees and homesteads of Baganda during the attack.

The agent at the Nyakishenyi gombolola, Abdulla Muwanika, survived by hiding on the roof of his house.

Retaliation

Killed...

The rebellion by the Bakiga lasted a day. But the Baganda-led retaliation lasted five days.

In the five days of revenge, more than 1,000 rounds of ammunitions were expended, 479 heads of cattle, 764 sheep and goats were taken by the Baganda.

The trial.

The trial was presided over by J.M. McDougall, the acting District Commissioner (DC), and assisted by two Buganda assessors.

Muwanika narrated the death of his guard Kasimbazi, the wife of one of his servants only identified as Merajuma, and a young man in his compound called Malisa. They were all speared to death.