Prime

Thief disrupts Rubaga as new baby arrives

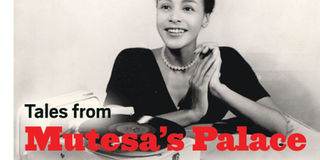

Barbara Kimenye and her sons Topha (L) and Daudi during a visit to Kabale District in the 1960s. FILE PHOTO

What you need to know:

New neighbourhood. Young and beautiful British-born Barbara Kimenye arrived at Port Bell by ferry from Bukoba, Tanzania, to start a whole new life after her marriage had fallen apart. It is a life that would see her mix with ordinary Baganda and bring her close to their king. In this second part of our serialisation of her unpublished book, Tales from Mutesa’s Palace, she writes about her new neighbourhood near the palace and the arrival of her second child.

A ragged hedge separated us from my next door neighbour Ms Miriam Daly, who professed to be a journalist, who with her naturally blonde page-boy hair, and strong features, always reminded me of pictures of Joan of Arc.

Nor did the resemblance to the saint stop short at physical features, for Ms Daly was always battling against what she saw as injustice, but I don’t believe she ever stepped outside her own garden without a little perky hat, gloves, bag and high-heeled shoes to complement whichever pastel-shaded full-skirted dress she happened to be wearing. She always looked to be on her way to a garden party.

Also, under one arm would be her Pekinese, Wu Fung. The pity was that Wu Fung rarely allowed to put paw on terra firma, had claws curving into his pads, and although Ms Daly was meticulous about her own appearance, it never seemed to enter her head that the dog needed a good brushing.

She introduced herself shortly after we moved in, and soon there was regular traffic between our two houses. She kept me supplied with books from her extensive library, and I am eternally in her debt for that alone.

With no radio, and television not yet on the Ugandan horizon, a good book read by lamplight was a very pleasant way of spending an evening. Otherwise, she kept Joyce and me enthralled with the endless saga of her love-hate relationship with the Baganda.

“They are such charming rogues!” she would helplessly exclaim, after some incident involving a battle of wits in which she had emerged the loser.

All this was harmless enough, but the same could not be said of Ms Daly’s pet monkey, Nefertiti. Nobody ever knew how she came by this unlovable animal which was notorious on our side of Rubaga Hill.

When Nefertiti had not freed herself of the long chain attaching her to a tree, and was out and about terrorising the neighbourhood, as frequently happened, she was hiding in the tree’s branches, her back to the path leading to the house, so that innocent visitors, not realising that she was watching every move they made through a hand mirror, imagined that they were going to pass her unscathed. It was a tremendous shock when she judged a person to be within striking distance, and pounced.

One night, or rather the early hours of the morning, I was awakened by urgent tapping on the shutters of my bedroom. It was Ms Daly, with a very exciting tale to tell. She was babbling the story before we had time to unlock the door and start the primus stove for tea.

It seems that she had raised her eyes from the book she had been reading in bed, seen one of the bedroom curtains edged aside, and a hand holding a knife glide between the bars of her unglazed windows.

Quietly yet quickly she had dressed, slipped out of the house through the back door, and walked more than a mile to the police station, attached to the Omukulu we Kibuga’s administrative building.

Our district being part of what was designated the Kibuga, or capital of the Kingdom of Buganda, and the Omukulu being the person in over-all charge, the police were quite separate from the central Ugandan government police force, and the academic standard not as high.

The young askari behind the desk refused to take any action before being supplied with Ms Daly’s personal particulars. It was bad enough that she had to repeatedly spell out every word for him. The crunch came when he dug in his heels and wouldn’t go a step further unless she told him her age.

“Over 21” cut no ice with this beauty. I have no idea how long the two of them argued this important piece of information. It ended with Ms Daly declaring the situation ‘ridiculous’, and flouncing off to Old Kampala Police Station, a Ugandan government post, and another mile or so away.

There her story received more attention. My guess is that the people on duty were probably bored to death on a quiet night, and welcomed the chance to get out and see some action. Anyway, they promptly flung themselves and Ms Daly into police vehicles and hurtled back with her to Rubaga.

Back at the ranch, or rather her pretty little baked brick bungalow, the scene had drastically changed.

For one thing, our local dignitary, Mr Mugwanya, a former Buganda Chief Justice (Omulamuzi), living on the other side from us of Ms Daly, employed an elderly, very conscientious night watchman. This old gentleman, noticing unusual activity in and around what was after all the home of a maidenly lady, had gone to investigate, surprised the would-be burglar, and let off a shot from the blunderbuss (a leftover from Buganda’s religious wars in the early part of the century) with which he was armed.

The burglar had retaliated by picking up a large rock and throwing it at the night watchman who received it in the solar plexus.

The police and Ms Daly arrived while the old night watchman was still fighting for breath and writhing on the ground, and the burglar had made his escape.

Naturally, the shot from the blunderbuss had not gone unnoticed. The neighbours were out in full force. Many had brought their children to witness the fun. Joyce and I were furious at having slept right through it. We put this down to the thickness of our walls. Even Ms Daly’s first-hand account of the proceedings didn’t make up for our not being on the spot.

However, while vetoing Ms Daly’s plan for an ambush next night (she insisted upon calling it a posse, and she was sure the burglar would return, although it was difficult to imagine what he might consider worth two trips to her house), the police had agreed to provide her with protection in the form of a constable, from six in the evening till six next morning, for the ensuing couple of weeks.

This was where our troubles, mine and Joyce’s, began. The constable assigned to Ms Daly’s protection was a handsome, six foot Acholi from northern Uganda, and she treated him as though he were a schoolboy nephew.

What she termed ‘schoolboy sandwiches’, i.e. massive slabs of bread stuck together by a thick layer of jam, and mugs of cocoa were constantly supplied to keep up his strength through the night. And in between being fed, the constable was sent to patrol the neighbouring premises for signs of any unlawful activity.

Ms Daly genuinely believed that she was being public spirited in sharing her police protection with the rest of us. I can only recall that it was no joke being jolted awake any time after 12 midnight by the sound of booted feet tramping heavily around the verandah. Nor were we the only people to suffer. Other neighbours were frightened out of their lives at hearing somebody plodding around outside their homes, and soon plots were afoot as to how to get rid of Ms Daly’s protector.

One suggestion was that Nefertiti be set free at about the time that the constable usually started his unappreciated patrol. The suggestion wasn’t taken up because we were all too cowardly to approach the monkey.

Even our local drunk, notorious for his recklessness when under the influence, couldn’t be coaxed into taking on the job. It was a classic case of “Who will Bell the Cat?” What relief when business picked up at Old Kampala Police Station, and they could no longer afford to allow an overfed constable to ruin our sleep on Rubaga Hill.

Of course, Ms Daly was grossly affronted. She spent days pleading for the return of what she had come to regard as her property.

As luck would have it, however, Joyce and I were not long among the grateful allowed to sleep in peace, because the constable’s disappearance coincided with Topha and I catching whooping cough.

Topha was then nearing his first birthday, and the medical opinion of the day was that no child under the age of 18 months could survive whooping cough in a developing country, for the reason that whooping cough and the spontaneous vomiting that accompanied it caused children to starve to death. I don’t know what the statistics were on pregnant women.

Joyce had other ideas. The moment she heard either Topha or me beginning that agonising, long drawn-out whoop, she was there to grip us between her clenched fists, one pressed against the chest, and the other in the middle of the back, to prevent vomiting. As a result, Topha never lost weight and recovered fairly quickly.

My ordeal was more prolonged. I couldn’t afford to stay away from work, and I still go hot all over when I remember how, overcome by a whoop, I would stand in the street, gasping helplessly before throwing-up in the gutter.

And whooping cough lasts for ages. For months after getting over the throwing-up stage, an ordinary laugh could turn into a nightmare of one of those long indrawn whoops, enough to make me feel that my lungs were bursting, and scaring onlookers who imagined I was mad.

The wonder is that in my anxiety to keep working, I didn’t start a whooping cough epidemic in Kampala. My only excuse is that there were no social security benefits available, employers were not obliged to pay for sickness or maternity leave, so seldom did, and I desperately needed the money.

New baby comes

The day Daudi, my youngest son was born, Ms Daly was prominent. She had never witnessed the birth of a child, and as a journalist, she thought she should. Everything began in the early hours of July 5, 1956. I woke up in a soaking bed, and shamefully put the sheets in a bucket of cold water, convinced that pregnancy had weakened my bladder. A couple of hours later, I was again changing the sheets, and wondering how to explain the extra laundry to Joyce.

I look back on this incident and marvel at my capacity for blinding myself to facts. Unbelievable though it may seem, it never once crossed my mind that the baby I carried was making its debut; I don’t remember anything so embarrassing happening when Topha was born.

Also, I had convinced myself that nothing would happen until my mother arrived from England in the following month. At seven that same morning, I was on my way to work. Somewhere down Old

Kampala Hill, a car stopped and the driver offered me a lift into town. He was an Italian mechanic, and his first words were “Are you all right, madam? You don’t look well.”

I thought that looking worried would have been a more fitting description, because although I felt fine, I was wondering how to cope in the office if I began leaking all over the place. At about 10 o’clock, a dear friend, Dee, wife of the top Pepsi Cola man in Uganda, whom I’d first met as a client of our insurance company, telephoned to see how I was.

It was a relief to unburden myself to her, and I promised to take her advice and call at the clinic run by the Ladies of the Grail at Rubaga before going home that evening.

But an hour later, Dee was again on the phone. She had suddenly remembered a similar incident connected with the birth of her daughter 16 years earlier. She insisted on collecting me from the office and taking me straight up to Rubaga Hospital.

The idea didn’t appeal to me: I had already wasted the hospital’s time on an earlier occasion with what Joyce had diagnosed as premature labour pains but which turned out to be wind.

Dee, however, was a very forceful if loveable woman. Ignoring all protests from me, she talked to my boss, put me in her car, and had me up at Rubaga Hospital within 30 minutes. The smug expression on her face said it all, after I was examined, and Sister Hannah told me to go home for a nightie and toiletries.

We didn’t need telephones at Rubaga. News spread quicker than it would take to dial a number. Within minutes of our arriving at the house, which was within walking distance of the hospital, neighbours, including Ms Daly, were crowding in, and Joyce was juggling with our limited crockery to serve everybody with tea.

I, as the object of interest and attention, was enjoying the party and asking Joyce if she could manage lunch for all of us, when Dee reminded me of our date up the hill, and whisked me off to the no-nonsense charms of Sister Hannah, a tough German Lady of the Grail who must have delivered half the population in our district.

Ms Daly insisted on coming with us. I bet she often wished she had stayed home. When the baby did make a start, and I let off steam by using disgusting language – for the Rubaga Hospital school of thought was that unaided natural birth was best – Ms Daly got out her rosary and prayed over me as though she were involved in exorcising. Dee was much more practical. She encouraged me to breath correctly and yell when I needed to.

Sister Hannah sternly told me to behave. But I’m not complaining about her. Because the maternity wing was full, I was being delivered on her own bed in her own room, and everything about her told me that I was in the best possible competent hands.

The moment Daudi’s head appeared, she took one look at the devastated Ms Daly and helped her away from the scene of drama. From then on, Sr Hannah divided her time between delivering the infant and attending to Ms Daly who was laid out somewhere, suffering from shock.

The whole episode from the first pain to the actual delivery had not taken much more than an hour, and less than an hour later I was on my way home with the child. If anybody needed further attention, it was poor Ms Daly.

White and shaken, the experience sought for the broadening of journalistic knowledge had clearly been too much for her. While Dee drove into town to buy things for the baby, Ms Daly sipped hot sweet tea, and fought back the tears as she declared that if men only knew how women suffered, they would surely treat them more tenderly.

The following day was memorable for an unexpected kindness. I awoke from an afternoon doze to the quiet buzzing of gentle voices, and when I opened my eyes and sat up, was astonished to see about a dozen Baganda ladies sitting on mats on the floor of my bedroom.

One old lady nursed Topha on her lap, and the rest were examining every feature of the new baby, Daudi. They were passing him from hand to hand, and clucking approvingly, and, incidentally, chewing coffee beans, obviously supplied by Joyce, and spitting out the husks.

They had come, Joyce told me, in the traditional manner to see if I had enough milk for “our child”: if I hadn’t, they would bring a herbal brew guaranteed to produce a plentiful supply of breast milk.

When it was demonstrated that there was milk in abundance, there were more approving duckings and satisfied noddings, and after taking tea the ladies went home.

They left me with a particularly comforting feeling. During both my pregnancies I lived in an unnatural state of euphoria. Worries never penetrated very deeply, as they did when I was back to normal, and I was at my healthiest and happiest for most of the time. Other women have said the same about themselves. It was almost as if there was a barrier blocking out fear and cushioning disappointments. Nothing disturbed the overall tranquillity.

But all that changed within hours of Daudi being born. As soon as I was alone, the barrier came down and misgivings arrived thick and fast. For perhaps the first time since coming to Uganda, I recognised the risks I was taking in hoping to raise two children on my own. The only money I had was the salary from the insurance company, and it allowed for no savings. I worried over how I would cope in the event of sickness, or if for some reason, I lost my job.

The visit from those ladies went a long way to restoring my confidence. Simply by showing an interest in what happened to me and my children, and referring to them as ‘abana baffe’ (our children) they had indicated that we were accepted members of the community.

Although this did not automatically wipe out the problems which were sure to arise, it told me that I was home, and that when and if things did go wrong, home was the best place to be. It was not a sentimental feeling. Comfortable describes it better. Incredibly enough, I had never before really felt at home anywhere.

-Continues in Saturday Monitor next week