Prime

Tales from mutesa’s palace: Boat cruise with Mutesa, birth of another prince

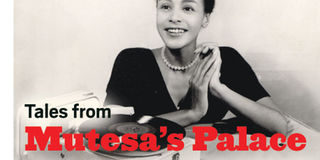

Kabaka Mutesa with Barbara Kimenye (R) and another lady at a social function. Courtesy Photo

What you need to know:

Outings. Young and beautiful British-born Barbra arrived at Port Bell by ferry from Bukoba, Tanzania, to start a whole new life after her marriage had fallen apart. It is a life that would see her mix with ordinary Baganda and bring her close to their king. In the fifth part of our serialisation of her unpublished book, Tales from Mutesa’s Palace, she writes about her first boat cruise with the king, and near fatal accident as they drove around the city. The first part was published in Saturday Monitor of September 26

The Kabaka’s being away from Mengo brought silence to our lives. All the time he was in residence and his standard flew over the new Twekobe, the royal drums were only ever silent for certain parts of the day. They marked his activities such as getting up in the morning (although this was more traditional than truth, for he was a notorious late riser), going to bed, meal times, leaving and returning.

They also produced special rolls of drums for, say, the visit of the governor, the Katikkiro or other dignitaries, including Ssaza chiefs. Some of the elders living on our hill knew from the drums as much as the Kabaka what was taking place in the Lubiri. My eldest son, soon after he attended nursery school in the palace grounds, also grew to understand these traditional announcements.

But while the Kabaka was away, the drums remained silent, and we missed them. Several of our neighbours remarked that the silence was reminiscent of his years in exile, when the entire kingdom put on a show of mourning.

Then, late one night, the drums burst into a frenzy of co-ordinated booms and thuds. They vibrated across the valley so that nobody was left in doubt of the Kabaka’s return home. The obsequious Michael turned up at our house a couple of days later on Saturday to say that His Highness requested my attendance next morning at 11 o’clock. A car would collect me. Eventually, I grew to accept Michael as part of the scenery, but never could I forget that he was nothing better than a pimp.

I was ready and waiting when the Land Rover came for me on Sunday morning, only this time there was no attempt at dressing up. It was a glorious day, and I wore a sleeveless blouse and flared cotton skirt, and went bare-legged in sandals. I was glad I did when I was dropped off at the palace and told that the usual gang were all set for a trip on Lake Victoria in the Kabaka’s launch, the Nguvu.

Other women in the party, Nalinya Mpologoma and a couple of other princesses wore, as usual, busuuti, but three accompanying the Omukama of Tooro, were done up as for a cocktail party, in lurex and high heels. The Omukama himself, just out of hospital or from a sick-bed, was in pyjamas and dressing-gown. George, as everybody called him, was a wonderful person. Like the Kabaka, he spoke English better than the average English person, only his voice was fruitier, and to him everybody was “darling”. He was tall, cuddly, witty and kind, and I loved him on sight.

We set off from the palace in convoy, with the Kabaka leading in a Lincoln and his standard fluttering from the bonnet. He was at the wheel, me beside him, and instead of heading straight for Port Bell where the Nguvu was moored; he made a detour to the arcade of shops beneath the Imperial Hotel in Kampala.

Although it was Sunday, one of the shops, ‘Idees’, was open, although from its chaotic window display, it was difficult to tell whether the owner was moving in or moving out. The owner - a thin Asian woman dressed in baggy black woolen sweater, tight black velvet pants, and glossy red one inch fingernails – gushed out of a back room as soon as we walked in.

This was Sulti Hajji, dress designer trained by the legendary Jacques Path in Paris, and destined to become one of my greatest friends.

The black outfit was sort of her trademark, a reminder that she had once mixed with beatniks and existentialists in France, and was not the usual Ismaili female type; but it was surely a high price to pay for an individual image in Uganda’s hot and humid climate.

Astonishingly, the Kabaka asked her if I would do, and Sulti looked me up and down as though pricing a piece of furniture, before saying that she thought so. Next she wanted to know if I had done any modelling, and explained that she was giving a dress show at Lubiri and was short of models. Although I was far from keen, the Kabaka assured both of us that he considered me perfect for the job, and arranged that I should attend rehearsals and fittings in the coming week.

We left Sulti (me in state of shock) and carried on towards Port Bell. Just as we approached a turning to take us to the dock, another car shot out and if His Highness had not been quick on the brakes, we could definitely have ended up as dead meat. As it was, the Lincoln came to a rest with its bonnet inches away from the side of the other car which contained a couple of very shaken and apologetic Italians.

We were all shaken for that matter, and there was a general air of relief when at last we climbed aboard the Nguvu, a modest launch with a small cabin below decks.

The crew wore uniforms copied from British Navy ratings, at Basil’s suggestion, but the big sailor collars were unlined, and every time there was a gust of wind the men’s heads were engulfed in a square of white cotton. It was surprising that nobody was lost overboard.

Cruise ride

For the rest, we sprawled about on deck, drinking and chatting, on our way to a picnic on one of the small lake islands. The island for which we headed was an uninhabited stretch of bush, and we had not penetrated far when the Kabaka, leading the way, walked straight into a stream of safari ants.

There was a slight delay while James Lutaya and somebody else took him behind a tree to strip him and shake the ants out of his clothing.

At the chosen picnic site, we ate matooke, chunks of roasted meat, and fruit, drank beer. It was a family party. Nothing fancy. The informality which His Highness enjoyed when away from stiff court protocol was unhibited. George had us all laughing over his stories of his and the Kabaka’s adventures during a holiday in Spain, and often the point of these stories was how the pair of them lost out. We strolled back to the Nguvu, very much on the lookout for more safari ants, and sailed as the sun was setting. The moon was brilliant in a cloudless sky by the time we docked at Port Bell and we drove back to Mengo feeling content and sleepy.

However, nobody was going to an early bed that night. As usual, the drums gave the Kabaka a rousing welcome as he entered Lubiri, then changed to a more tempestuous beat. The Kabaka grinned broadly, and the princes sitting in the back of the Lincoln began thanking him for giving the kingdom another son.

At the old Twekobe, servants quickly produced champagne. By now, the drums had reached such a crescendo that it was impossible to hear what anybody said. We mouthed at each other like characters in a silent film. The Kabaka went away and came back carrying a beautiful little boy of about 18 months old, wearing a white nightshirt.

This was Prince Ronald Mutebi, whose mother Sarah, sister of Nnabagereka, and the Kabaka’s childhood sweetheart, and who bore the title Kabejja (head of princesses), had that evening given birth to another son to be named Richard Walugembe.

Prince Mutebi was very sleepy on the night of Walugembe’s birth and ought to have been allowed to stay in bed, but the Kabaka insisted on taking the child to see his new brother at Mengo Hospital, and after watching the two of them depart in a palace car, we guests went to our homes in the sudden silence which had descended with the Kabaka’s being driven out of Lubiri and to Mengo Hospital.

So ended the first of many happy trips on the Nguvu. In between, I made a whole new set of friends through preparing for Sulti’s fashion show. Twice a week during the ensuing month, I was called to Idees for fittings and photo sessions for the programme. Then to practice walking on the catwalk set up in the Imperial Hotel Ballroom.

Of the other models, I best recall Doreen Davis, an Anglo-Indian married to a Makerere University lecturer, who was determined to be a singing star. Small and pretty with masses of black silky hair, she looked the part, but unfortunately, as her self-produced records revealed, the singing voice was a disaster.

Her big rival in the modelling game was an English girl, owner of a smart and expensive boutique, who eventually married the American Ambassador to Uganda. She and Doreen loudly bragged about their previous modelling experience, and almost came to blows over who should head the list of models in the programme.

Besides these two, there was another English girl as bewildered as myself, who told me that she had been roped in by Sulti when she had popped into Idees to ask the way to a certain doctor’s surgery, and the wife of Abdul, the Swahili barman at Speke Hotel.

This pretty girl didn’t have much to say for herself, but created an envious silence whenever we were changing into Sulti’s outrageous creations, because of her astoundingly beautiful underwear. She wore a bui-bui, the black cotton cover for Muslim women, over quite ordinary dresses.

Underneath, however, were matching bras, panties and petticoats of the most delicate and lacy fabrics. Even Sulti was moved to remark that Abdul’s wife must get her lingerie from Paris. John Ayres, acting manager of the Imperial Hotel, who was to compere the fashion show, entered my life one glorious afternoon.

The preparations for the show had reached the stage when we models were expected to be at Idees during our lunchtimes for fittings, and I arrived at the same time as a heavenly creature – tall, blonde, elegant limbs shown off to perfection in pale pink sports shirt, and, unusually, for those days, very short shorts.

In other words, John Ayres. I was half-way in love with him until it was tactfully pointed out that while he enjoyed female company, he was decidedly more attracted to men.

Otherwise, John was wonderful at pouring oil on troubled waters. At the dress rehearsal in the Imperial Hotel ballroom, as the rivalry between Doreen and the boutique owner came near to fisticuffs, and the rest of us were trembling at the thought of having to try walking in Sulti’s tight-skirted extravaganzas, John suddenly appeared with two waiters bearing trays of smoked salmon sandwiches and glasses of white wine.

He teased and joked until we were at least brave enough to attempt the catwalk.He wasn’t quite so successful on the night. The girl who had been roped in to model on her way to the doctor found that Sulti had altered the seams of a full-length sheath dress so that it was impossible to put one foot in front of the other without toppling over.

The poor girl had to be lifted bodily onto the catwalk in the front garden of the new Twekobe, then simply stood there in front of an audience of diplomats, government officials and Kiganda dignitaries, wishing the ground to swallow her up. At the end of John’s glib description of the gown, she gratefully sank backwards into the waiting arms of two palace servants who carted her back to the dressing-room.

Another treat

The show was repeated at State House for the benefit of the governor’s wife, Lady Cohen, and invited friends, but the Lubiri show was important to me because as soon as it was over and the models allowed to circulate among the guests, I got into conversation with a woman who worked as secretary to the permanent secretary in the Kabaka’s government ministry of Education.

She was about to leave with her husband who had been given a posting in Britain, and she suggested that I apply for her job. She introduced me to her boss, Harry Hudson, who also encouraged me to apply, and so, within a few weeks, and after taking the required Protectorate Government shorthand-typing tests, I said goodbye to my friends at the insurance office and was on secondment to the Kabaka’s government at Mengo.

Continues in Sunday Monitor tomorrow