Prime

Debt crunch: Africa is a net creditor to the rest of the world

Mr Jason Braganza explains Africa’s debt situation. PHOTO/file

What you need to know:

During the course of the second AFRODAD Media Initiative (AFROMEDI) the executive director of African Forum and Network on Debt and Development (AFRODAD), Mr Jason Braganza explained why the continent needs to start assuming the role of rule maker rather than rule taker to deal with debt issues

Africa’s borrowing appetite has reached a level where something may have to give in. In an interview with Prosper Magazine’s Ismail Musa Ladu during the course of the second AFRODAD Media Initiative (AFROMEDI) held in Nairobi, the executive director of African Forum and Network on Debt and Development (AFRODAD), Mr Jason Braganza whose Pan-African organisation is committed to finding solutions to Africa’s challenges in debt, resource management and financial development, explained why the continent needs to start assuming the role of rule maker rather than rule taker to deal with debt issues. Excerpts...

What do you think about the current debt situation in Africa and what drives the insatiable appetite to borrow?

The debt situation has gotten worse. For the last decade, we have seen an increased appetite amongst many African countries to borrow quite heavily to finance their development agenda. Many countries in Africa are steadily slipping from low and medium to high debt distress levels. For the case of Zambia, we are seeing default already. The Covid-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the already disturbing situation. This threatening debt crisis is happening just two decades after debt restructuring under Heavily Indebted Poor Country Initiative (HIPC) and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). Already gross government debt which reflects the total liabilities for countries to be debt free has been on a consistent rise in the African continent and for all regional economic communities for more than 20 years. It rose from about $192 billion in 2000, to over $1.5 trillion in 2020. This is way above the revenue earning potential for the region which stood at $43.2 billion and $457 billion during the same period. This is a clear indication that African countries have been borrowing above their earning potential – a situation that has been compounded by the outbreak of Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

One of our major concerns is about the nature of borrowing which is no longer on concessional terms as has been the case in the early parts of the 2000s. We are increasingly seeing dealings by the continental governments with non-traditional and bilateral lenders. This is in addition to a huge explosion in commercial and private lending which means the terms and conditions of loans are increasingly getting worse.

Have the debt relief measures been as helpful as anticipated earlier?

There have been incidences where debt relief measures have not been as useful as they were thought. As we deal with that fact, African governments will also have to deal with emerging crisis in form of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine which will certainly put fiscal pressure on our governments by way of either rising fuel prices or food shortages -- and all of these combined could compel governments to rethink their fiscal (revenue mobilisation) positions. We think it could trigger another wave of borrowing even as the continent is trying to come out of the Covid-19 crisis.

As that plays out, we have in recent times seen a number of debt initiatives such as the debt service suspension initiative, we have also seen the 20 largest economies in the world come up with something called the Common Framework on the Treatment of Debt.

We have also seen the IMF Special Drawing Rights which is a special reserve currency that is available and accessible to all members of IMF. This is not a story of success but a story of where Africa lies in the hierarchy of needs when there is a global crisis. As of January 2022 the Debt Service Suspension Initiative which ended in December 2021 is now due for servicing at a time when economies in the continent are trying to find their footing.

What is the continent’s problem in mobilising its own resources rather than heavily borrowing?

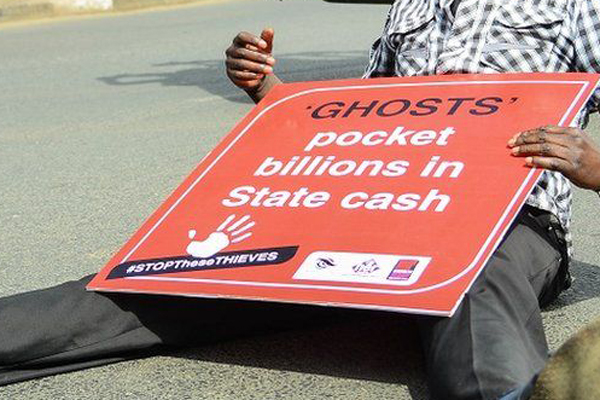

We need to look at the structure of our economies in the continent and make it work more efficiently for us in terms of generating optimum returns. We are still producing very low value agricultural commodities, thanks to the weak value chain that does not facilitate value addition. This has an impact on revenue mobilisation. Also, most of our economies are heavily relying on primary commodity exports which are very vulnerable to price shocks and related development. The continent also needs to decide how to deal with the issue of fiscal (revenue) leakages. We lose billions of dollars every year through illicit financial flows (IFFs) and I think the latest estimates the continent is losing as a result of this fraud and related scam is in the range of around $100 billion a year. Illicit financial flows come in many shapes and forms. It could be tax related, crime, corruption or even debt related. Then we must end the obsessions with economic growth rather than the actual development.

When we speak of development, we mean proper investment in the social sector such as education, health, water and sanitation, food security and agriculture among other key sectors that are the mainstay of our economies in the continent.

Given the exploitation of our natural resources, both beneath and above the ground, and looking at how much we lose in form of IFF and related fraud – we are compelled to believe that Africa is a net creditor to the rest of the world. This is because estimates show that for any dollar that comes to Africa – three dollars leave the continent. Because of that, we deserve to sit at the table setting the development agenda at all levels when it comes to commerce, trade, finance and economics.

So where does Uganda stand?

Uganda is persistently knocking the door of members in the category of high risk of debt distress. The countries in these categories include: Congo, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Gambia, Guinea, Ghana, Kenya, South Sudan, Togo and Zambia. Countries under moderate to low risk of debt distress include: Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Mali, Malawi and Senegal). Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Chad, Nigeria and South Sudan are faced with longstanding conflicts which have serious implications on borrowed resources as they affect the quality of the economic environment required for proper investment of borrowed resources or even cause the diversion of such resources to finance conflict.

How is the mantra - Africa not a rule taker but a rule maker relevant in the debt engagement?

We want this narrative to act as a stark reminder to our governments across the continent. Covid-19 pandemic has shown how integral our resources are to the global trading system. Trade came to a standstill during the peak of the pandemic. So many industries suffered because they could not extract or exploit resources from Africa.

So when we talk about Africa as a rule maker and not a rule taker, our expectation is that our leaders while in several summits abroad realise that they are not there for donations but to engage and state the position of the continent. We want them to have the courage to say we can make our vaccines and every other essential thing needed in life and supply them across the continent and wherever there is need.