Okot p’Bitek’s Song of Lawino reechoed

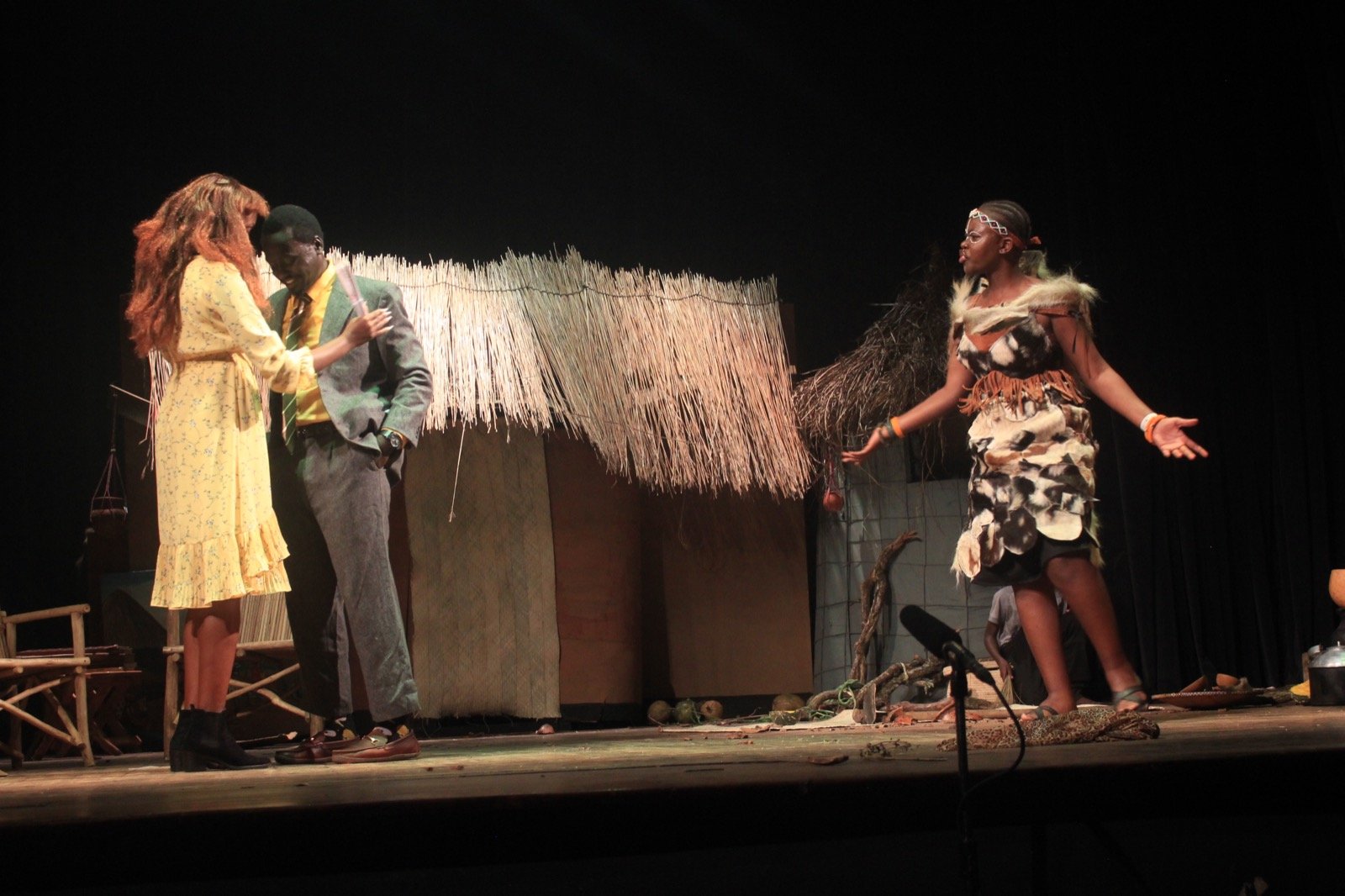

Destiny Chaiga, Okello and Awino in one of the scenes. Photos/Courtesy

What you need to know:

- Song of Lawino is a remarkable and thought-provoking epic poem written by Ugandan poet Okot p’Bitek.

- The only problem is that if you do not grasp Acholi, which was a few of us in the audience, these moments make you feel like a tourist, but besides the language barrier, the energy and colour they brought onto the stage always change the mood.

If you have appreciated Uganda’s literature even for a day, chances are high you are familiar with Okot P’Bitek’s Song of Lawino, translated as Wer pa Lawino in Acholi.

Song of Lawino is a remarkable and thought-provoking epic poem written by Ugandan poet Okot p’Bitek. Published in 1966, the poem presents a powerful critique of the clash between traditional African culture and the encroachment of Western influences. Through the voice of its protagonist, Lawino, the poem, explores themes of identity, cultural pride, love, and the erosion of African traditions.

Last weekend, as many music lovers chose to be paralysed by both Pallaso and Alien Skin’s concerts at the National Theatre, something special was happening. The theatre was playing host to Echoes of Lawino, a production by Okere City that is not entirely re-imagining but re-echoing the man’s poem many years later.

There is a very big history that Okot P’Bitek has with the institution and the building that is the National Theatre; he was the first executive director, and thus, having the show staged there was a big deal.

With a talented cast of Sharon Atuhaire, Destiny Gladys Chaiga, Ojok Okello and Awino Mercy. The show is qualified as a musical by a 40-member singing and dancing troupe whose songs in Acholi breakdown the plot while getting the mind ready for the next act.

The only problem is that if you do not grasp Acholi, which was a few of us in the audience, these moments make you feel like a tourist, but besides the language barrier, the energy and colour they brought onto the stage always change the mood.

Echoes of Lawino is not entirely an adaptation of Song of Lawino; it is inspired by the famous poem but also brings along Song of Ocol, which seems to be a commentary on the famous poem. This production seems to bring the two poems together, and in the process, they critique and comment on society today.

Sharon Atuhairwe in one of the scenes with Ojok Okello

Portraying Lawino

The strength of Song of Lawino lies in its raw and unapologetic portrayal of the tensions between tradition and modernity. Lawino’s voice is unfiltered, passionate and evocative, representing the voice of many African individuals grappling with the changes and challenges brought by colonialism and Westernisation. The poem effectively captures the internal conflict faced by Lawino as she witnesses the abandonment of her cultural heritage by her husband, Ocol, who is seduced by Western values.

The show’s director, Alex Kitaka, manages to capture many of these values with his two actors, Atuhairwe and Awino, who shared the role of Lawino. Atuhaire, who comes from Western Uganda, even though she is a brilliant actor, struggled a bit with her intonations, especially when pronouncing names. That may have been the reason Awino stepped in as the show went into the second act.

For most of the time, Lawino is talking to her husband, Ocol, who has been seduced by Western culture and has chosen to dismiss everything he knew as he was growing up. Not even the fact that he is the son of a chief helps. His second wife, the polished, affluent one, represents Western seduction and his betrayal towards Lawino.

Lawino’s poignant and emotional expressions of love for her husband, despite his rejection of their shared culture, create a sense of deep empathy and heartache. The poem explores the complexities of love in the context of cultural clashes and sheds light on the far-reaching consequences of these conflicts on personal relationships.

The show’s biggest strength lies in the acting and the might of the source material. The production design of a grass-thatched hut, a granary, and a three-stone stove transported the audience to a random African village.

The play’s monumental scene was Ocol talking on a podium, addressing all the evils that continue to plague the country even after independence. The monologue covers corruption, embezzlement and empty politics.

Was that Ocol accepting that Western civilisation was not all that? Maybe that is a story for another day.