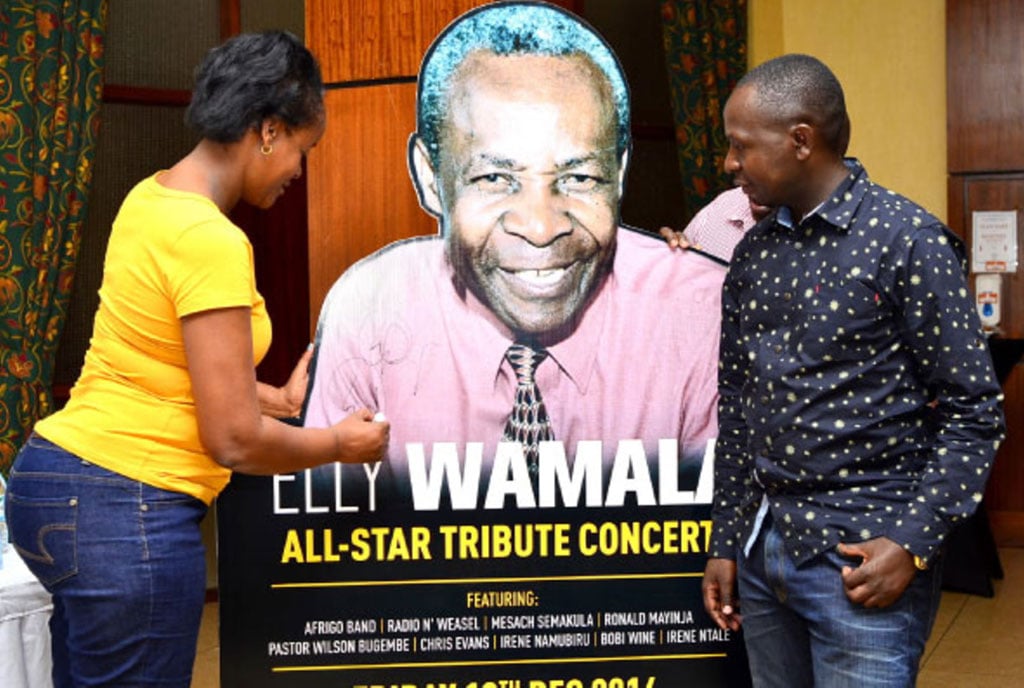

The late Kadongo Kamu founder, Elly Wamala. The music maestro later abandoned the genre he created. PHOTO/FILE/COURTESY

Entertainment

Prime

Why musician Wamala founded Kadongo Kamu, later deserted it

What you need to know:

- The genre’s genesis, although not pinpointed to a specific moment, took formal shape in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

- Undisputedly, it gained momentum with the formal recording of its pioneer song, Nabutono, by Elly Wamala.

Kadongo Kamu, Uganda’s oldest mainstream music genre, holds a special place in the nation’s musical history. The term “kadongo kamu” in the Ganda language translates to “one little guitar,” encapsulating the genre’s essence—crafted with a single acoustic, non-electric six-string guitar.

The genre’s genesis, although not pinpointed to a specific moment, took formal shape in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Undisputedly, it gained momentum with the formal recording of its pioneer song, Nabutono, by Elly Wamala in 1959, followed shortly by Josephine. Wamala’s lyrics, deeply rooted in local literature, blended with folk melodies and rural-style storytelling, quickly resonated with Ugandans, earning Kadongo Kamu a special place in their hearts and inspiring other local artists of the time.

Despite being the driving force behind the genre, Wamala took an unexpected turn in his musical journey. The pioneer of this indigenous style made a conscious decision to step away from it, embracing a more urban and contemporary genre, reminiscent of foreign stars like Belafonte and Lord Kitchener, whom he sang about in his 1998 single, “Ebinyumo Ebyaffe.” This departure showcased Wamala’s versatility, drawing influences from global musical landscapes.

Wamala’s move, however, did not hinder the genre’s growth. Kadongo Kamu flourished, propelled by other artists inspired by or who had started their careers with Wamala. Christopher Ssebaduka, Eclas Kawalya, Fred Masagazi, Dan Mugula, Fred Mbalire, Peter Baligidde, and Fred Kanyike, among others, actively contributed to the genre’s development in the 1960s and 1970s.

Hits such as Oluwala Olunyunyusi by Ssebaduka and Agawalagana Munkola by Baligidde further popularized Kadongo Kamu. These songs featured raw, unfiltered lyrics addressing societal issues, love, politics, and everyday life, connecting with people on a profound level.

As new stars rose to prominence, Wamala’s original status as the face of Kadongo Kamu evolved. Ssebaduka, for his strong dedication to the genre, earned the title of the “grandfather” of Kadongo Kamu, a genre initially brought to the forefront by Wamala.

Why Wamala left

A true pioneer music maestro in Uganda, Elly Wamala, created his initial songs by overlaying his voice on beats played with a single guitar in what would later be recognised as Kadongo Kamu. Music critic and analyst Joseph Batte asserts that Wamala’s understanding of music dynamics, honed through training in Nairobi and studies in Britain where he earned a diploma in Banjo, Mandolin, and Guitar (BMG), was the driving force behind his creative vision.

With this musical background, he aspired to craft something distinctive—an exclusively indigenous form of popular music that could genuinely be labeled as Ugandan.

Upon recording Nabutono, his dream began to materialise, catching the attention of the nation, particularly King Edward Muteesa, who frequently summoned Wamala to perform the song at his Banda palace. Muteesa even gifted him a guitar. However, Wamala grew disheartened by the emerging artists who adopted his style.

In the early 2000s, Elly Wamala shared with Batte that the musicians and groups embracing the genre lacked adequate knowledge of music fundamentals, leading to subpar performances. According to Wamala, these artists played informally without expanding their guitar chord vocabulary beyond the basic first degree (tonic), fourth degree (sub-dominant), and fifth degree (dominant).

Being a perfectionist and principled man, Wamala also criticised the names these artists gave their groups, such as Entebbe Guitar Singers, Kadongo Kamu Super Singers, and Matendo Promoted Singers, among others.

Despite performing for the Kabaka, Wamala disapproved of Kadongo Kamu artists staging street concerts in Kampala for a modest fee. He distanced himself from such practices.

Frustrated, Wamala abandoned the genre he initiated and embarked on creating music in a more sophisticated and unique style, challenging to imitate. He began writing music in calypso notations, distinct from the Kadongo Kamu style. Drawing on his linguistic background in poetry and prose from Makerere College, Wamala produced music with a more elaborate and ornate composition.

Furthermore, his son, James Muwanga Wamala, reflects that Elly Wamala shifted his style based on the experiences and exposure he gained along the way. Muwanga believes that his father only created Nabutono out of circumstances prevailing at that time.

Wamala there-after

Wamala’s musical evolution opened new artistic horizons as he transitioned to a style relying on a symphony of multiple instruments, embracing urban and contemporary sounds. This allowed him to connect with a broader audience, both locally and internationally. His seamless blend of traditional elements with modern beats showcased his versatility and adaptability.

According to his son Muwanga, Wamala continued to invent, introduce, and solidify elements for Uganda’s then-infant recording industry. Joseph Batte, whose father, Edmund Batte, produced most of Elly Wamala’s songs, shared that Wamala became more creative, writing his own music, including harmonies and guitar chords. This made working with him even easier. Most of his famous songs, except Nabutono, were in this new style, deviating from Kadongo Kamu.

Wamala’s departure from Kadongo Kamu sparked a renaissance, inspiring emerging artists to experiment with their sounds, creating a diverse tapestry of genres. Moses Matovu of Afrigo Band described Wamala as the mentor of all subsequent Ugandan musicians, as they grew up listening and learning from his music.

Stella Namatovu, a musicologist and cultural historian, offered valuable insights about Wamala’s transition, noting, “Kadongo Kamu was a revolutionary genre celebrating our cultural heritage and providing a platform for social commentary. Wamala’s exploration of another contemporary genre reflects the fluidity and dynamism of artistic expression, a testament to the ever-evolving nature of music and its ability to transcend boundaries.”

Namatovu emphasised that Wamala’s legacy extends beyond his individual contributions. The ripple effect of his musical journey has influenced subsequent generations of artists, shaping the trajectory of Ugandan music beyond a single genre. “The dynamic relationship between tradition and innovation is a constant theme in the narrative of musical pioneers like Wamala, who navigate the delicate balance between preserving heritage and embracing the winds of change,” she added.

Wamala’s exploration of a contemporary genre did not come without challenges. The transition faced skepticism from some purists who considered Kadongo Kamu a symbol of Ugandan identity. Critics argued that Wamala’s departure from the genre he pioneered was a betrayal of the essence he sought to preserve, as per Namatovu, who enjoyed watching Wamala perform at New Life Bar in Mengo at the time.

About Elly Wamala

Elly Wamala was born Elishama Lukwata Wamala on December 13, 1935 to sub-county clerk Ignatius Mutambuze and Gladys Nabutiti in Bulucheke, Mbale. He was the third of 19 children. He was raised in Bulenga on Mityana road, by his paternal uncle, Daniel Katunda. His musical talent was spotted when he was five years old, and his uncle started to call on him to entertain his frequent visitors.

Kadongo-Kamu today

Over the last 60 years, the genre has undergone many transformations but has remained true to its central purpose: communicating traditional wisdom and morals through anecdotes, stories, and social commentary. The earliest ‘Kadongo Kamu’ musicians accompanied their stories only with the Endongo (the bowl-lyre of the Baganda people), while later generations turned to drum machines and electric guitars. Today, what is now called kadongo kamu is quite different, as over the years, producers have changed the original dynamics of producing the genre.

Although they come with modern technology, which notably, among many things, has improved sound, it has placed the original Kadongo Kamu in a zone of close extinction. What we describe as kadongo kamu today actually bears little resemblance to the original style. The new kadongo kamu music sounds more like mainstream pop. Many of the artists considered genre strongholds today are actually detached from the genre’s folk roots.