Prime

Book Review: How a strong civil society can help Uganda develop

What you need to know:

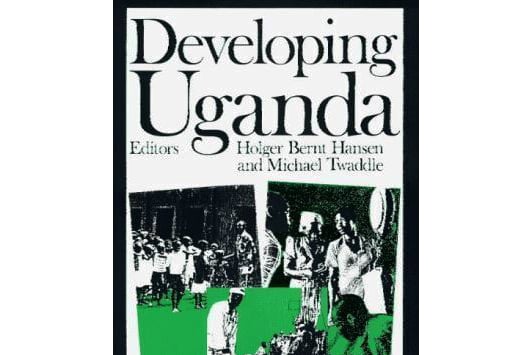

Book title: Developing Uganda.

Editors: Hölger Bernt Hansen and Michael Twaddle

Price: Shs20,000

Where: Aristoc Bookshop.

Pages: 293

The book was published in 1998.

On August 4, 1972, President Idi Amin gave Uganda’s Asian population 90 days to leave the country. Amin reportedly followed a dream featuring God ordering him, in a booming baritone, to expel them.

It was also reported that Amin alleged Uganda’s Asians had been “sabotaging Uganda’s economy, deliberately retarding economic progress, fostering widespread corruption and treacherously refraining from integrating in the Ugandan way of life.”

Another report has it that Amin showed Uganda’s Asians the door because he was rejected, in his romantic advances, by the widow of one of the wealthiest Asian families in Uganda. Amin reportedly proposed to the widow, in much the same manner a young Adolf Hitler reportedly fell under the spell of a Jewish maiden, only to be rebuffed and that is when he turned his metaphorical guns on Uganda’s Asian community.

Whatever the case, Uganda’s Asian community, which represented less than one percent of the population (there were 80,000 of them in a population of about 12 million), were responsible for around 90 percent of Uganda’s tax revenues. Their expulsion had profound economic consequences that led to Uganda’s economy spiralling.

Against this background, the book “Developing Uganda”, edited by Hölger Bernt Hansen and Michael Twaddle, sets forth Uganda’s recovery since Museveni came to power in 1986. Museveni’s economic policies, hewed to the Washington Consensus, performed reconstructive surgery (as opposed to cosmetic surgery) on the country in the early years of his rule.

Essays by academics, Ugandan and foreign, officials of international organisations chart Uganda’s growth out of poverty to development at the grassroots level. This is done in the context of several monetarist policies channeling economic liberalism and state retreat. Museveni’s regime was required, then, to create an enabling economic environment, political stability, promote human rights and “a sound policy framework aimed at strengthening the working of markets.”

However, that is not all. Alongside the structural adjustment policies proposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, donors like Danida redirected funds to the social sector as a further precondition of financial assistance.

Accordingly, the 20-20 principle was introduced at the 1995 Social Summit in Copenhagen whereby a shared effort saw donors allocating 20 percent of their aid to health and education in return for Museveni’s government allocating 20 percent of its budget to the same social sector.

Again, in an effort to link the national budget to the annual growth rate, Uganda’s government was instructed to become revenue-generating instead of revenue-consuming. This book ably shows how this was done in the shadow of a colonial legacy that left Uganda as a “patchwork of district administrations subdivided into counties and consolidated into provinces.”

That was part one

In the second part of the book, “Growing out of poverty”, Peter Collier and Sanjay Pradhan look at the economic aspects of the transition from civil war. Delving into the macro and micro-insecurities caused by the civil war of the 1980s, the two writers reveal private as well as government revenue and expenditure responses in the post-war period in helpful detail.

The third essay has Ian Livingstone writing about “Developing industry in Uganda in the 1990s.”

In the following chapters, responses to the HIV/AIDS scourge and its impact on the economy dance across the pages like a swirling dervish choreographed by policies familiar to Ugandans who were of age or came of age in the 90s.

Beyond the policy of privatisation, analysed here by Geoffrey B Tukahebwa, it is intriguing to see that the earlier policies of the National Resistance Movement (NRM) were calibrated to clip its monolithic wings.

It was agreed that the state played a role that was too pervasive and so state retreat was in the interest of the country. It was imperative, it was believed at the time, that there must be realistic alternatives to the state as a mobiliser, organiser and manager of resources. Accordingly, civil society was to be nurtured as a counterweight to state power.

How things have changed

Today, we see the exact opposite happening as the state is growing to the exclusion of any alternatives to its power. Yet we are warned here that civil society is an essential brake on any “tendencies towards a return to the role the state played from the early 1960s to the early 1980s” where unlimited state action led to unqualified state collapse.

In Chapter 19, Heike Behrend looks at insecurity and the aftermath of the Holy Spirit Movement, the embryonic rebel outfit of the Lord’s Resistance Army.

She writes about religious discourses which cement Uganda’s socio-political order. yone interested in the way politics is conducted at the top level in the region, the fears of our presidents, their day to day lives, and those around them, will like it. Great book.