Prime

Goodall on why humans must seize conservation

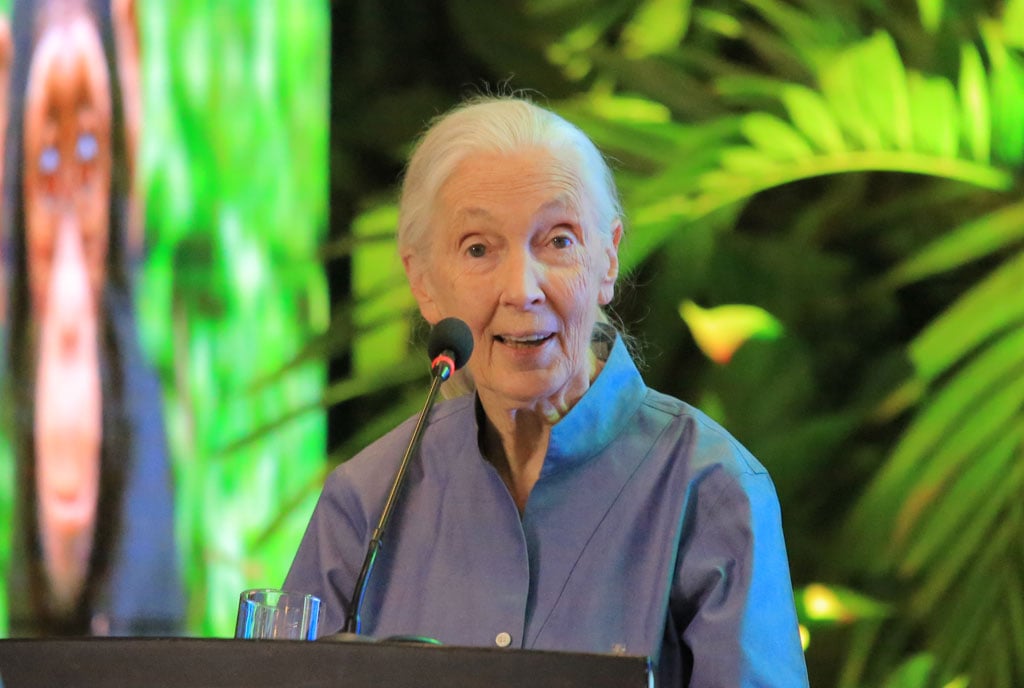

Jane Goodall during the public lecture ahead of the Ngamba@25 celebrations in Kampala on August 22, 2023. PHOTO/CLAIRE ZERIDA BALUNGI

What you need to know:

- The primatologist urged Ugandans to play their part in ensuring a favourable and holistic ecosystem for fellow primates.

In what has been widely described as a hopeful book, Jane Goodall, who is famed for her work studying the chimpanzees of Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania, shares a number of anecdotes. There is one in which she ends up with a dislocated shoulder and cracked ribs after rolling down a steep gravel trail with a chimp pressed against her chest. That was in 2016.

In The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times, which Goodall co-wrote with Douglas Abrams, the 89-year-old primatologist uses her lived experiences to offer hope. On a trip to Kenya in her early 20s, Goodall met the palaeontologist Dr Louis Leakey whilst out in the Serengeti. She was offered the opportunity to study chimpanzees. The rest, as they say, is history.

Goodall, who drinks a whisky every night for medicinal purposes since her mother introduced her to what has now become a ritual, travelled 300 days a year before the Covid-19 pandemic reared its ugly head. She has not made a secret of her wish to gradually return to the number.

In her last year as an octogenarian, the primatologist visited Uganda last week. Goodall, consistent as ever in her message, urged Ugandans to play their part in ensuring a favourable and holistic ecosystem for fellow primates.

The UN Messenger of Peace, chimpanzee conservationist and founder of the Jane Goodall Institute was in Uganda in time to mark the 25th anniversary of Ngamba Island, home to more than 52 orphaned and rescued chimpanzees.

Goodall is not sure what sparked her interest in chimps. The primatologist swears she came with it to the world. Her heart for the primates, whom she insists are the closest living relatives of human beings in the world today, is rooted in all the lessons she has been lucky to learn about the chimps over the years.

The parallels she draws between humans and chimps are multiple. Like humans, primates are distinct from each other. Their communication—the kissing, holding hands, begging for food with hand-out-stretched—is not different from that of humans. Indeed, like humans, chimpanzees can have contrasting strains that are at once dark, if brutal, and compassionate, if truly altruistic, living side by side.

These and the many more biological similarities to human characteristics are the reason chimps are deserving of the right to security, love and a sustainable supply to all basic needs. Humans and chimps, Goodall notes, share 96.8 percent of DNA composition. They have minds capable of solving problems, emotions such as happiness, despair, anger et cetera.

For the sake of the chimps’ safety, the Jane Goodall Method of Community-led Conservation was established starting from Gombe, Tanzania, by the Jane Goodall Institute. It started in 1977 with the hope of redefining traditional conservation, having learned that conservation started with the wellbeing of the communities neighbouring chimpanzee homesteads.

The method has supported locals to grow more food, develop water management programmes and to check deforestation. It has provided microfinance opportunities and supported the communities to start their own environmentally sustainable projects and it has offered family planning support.

“When I began in Gombe, a woman, on average, had eight to 10 children. They could not afford to educate the children anymore. We had to find ways on how to space the family in a reasonable way,” Goodall recalled, adding, “That programme has been so successful. We have added sophisticated technology like Geographic Information Systems, Global Positioning System satellites. We’ve helped the villages raise the money to make land use easy with land plans and we’re beginning to use this technology to survey other areas where there are chimpanzees, including Uganda.”

In her 2021 book, Goodall, true to her reputation as an optimist, outlines four things that make her forever hopeful: human intellect, the resilience of nature, the power of young people and the “indomitable” human spirit. During her recent visit to Uganda, Goodall expressed her confidence in the human race getting to understand the importance of protecting the environment. She revealed that past experiences suggest that this tends to happen gradually.

“For the first four years, we didn’t even talk to the villages about wildlife. We talked about having food in their homes and then they began to understand that saving the environment is also saving the future for their children and grandchildren and for the future generations,” she disclosed.

The programme is currently running in Tanzania, Uganda and four other African countries.

Conserving for generations

During Goodall’s recent visit, Sam Mwandha, the executive director of Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA), used a reflective session to note that humans —their intelligence notwithstanding—are inflicting telling damage on the ecosystem. He summarily urged Ugandans to conserve for generations. This conservation theme, he hastened to add, dovetails with the Roots and Shoots, an action programme propped by the Jane Goodall Institute. The programme empowers, especially young people, to be ambassadors of change in their communities.

A group of the Roots and Shoots pupils of St Theresa Primary School, Entebbe, wowed the guests with their well-rehearsed chorus, “Together we can, together we will, we must change the world.”

Goodall, in her concluding remarks, emphasised the main message of the Roots and Shoots.

“It’s not too late. We have a window of time. When we get together and take action together, we can make ethical choices every day,” Goodall said, adding of the inroads made, “they may feel small but they will make a huge difference.”

For context, she noted that humans have got time to at least slow down climate change and build up biodiversity, do something about pollution and change from industrial farming to more environmentally friendly forms of growing food like permaculture.

Multi-sectoral approach

The country director for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), Mr Simon Takozekibi Nampindo, drew attention to the need for diffusion of tensions among different forces of nature. He proceeded to point to a multi-sectoral approach in conservation that entails building a connectedness between forestry, agriculture, water and all different sectors.

He called on all stakeholders to start thinking of nature as a risk mitigation measure and become deliberate while investing in nature and not just pay lip service to corporate social investment.

“Communities that suffer losses need to hear our voices and deepen their connectedness to nature,” he begged.

It is this kind of “indomitable spirit” that Jane Goodall, who is famed for her work studying the chimpanzees of Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania, pointed out as one of her reasons for hope. This spirit, she taught, is one among people who tackle what seems impossible, they don’t give up and, in the end, they so often succeed and when they do, there are people around them who will carry on that message after they are gone.