Left to right: President Museveni, former vice president Speciosa Wandira Kazibwe and Dr Martin Aliker (right) wait for the arrival of former Kenyan president Daniel arap Moi at Entebbe airport. Photos/FILE

As the bells fall silent on the long life of Dr Martin Aliker, a member of the medical community, scion of a prominent political family and jet setting corporate operator thus quieter too is the old-fashioned idea of that a man may be judged by his word, advanced by the reputation of his industry and attain the right to hold his own opinions by the reward of his sweat.

Aliker held the keys to many revolving doors through changes in government in Africa to corporate upheaval, able to reach a paranoid rebel leader as much as a president or a CEO.

In it all he never sought to embellish his vast network in a way recognisable in today’s self-promoter. To the contrary, he worked better in small rooms and with individuals almost always allowing diverse interests to unite foes and friends alike.

Former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

From lunch with the Queen of England to meetings with the late Muammar Gaddafi in which he was involved in efforts to bring Libya out from the cold of isolation over the Lockerbie bombings to contact with the leaders of Apartheid South Africa, when the rest of Africa was on a war footing with the racist authorities in Johannesburg, Aliker’s story sometimes reads like a John Le Carre novel.

Aliker grew up in a polygamous home of a prominent Acholi family. His father Lacito Lokech, was an energetic Anglican covert who rose within the ranks of the colonial village elite to the rank of Rwot or chief.

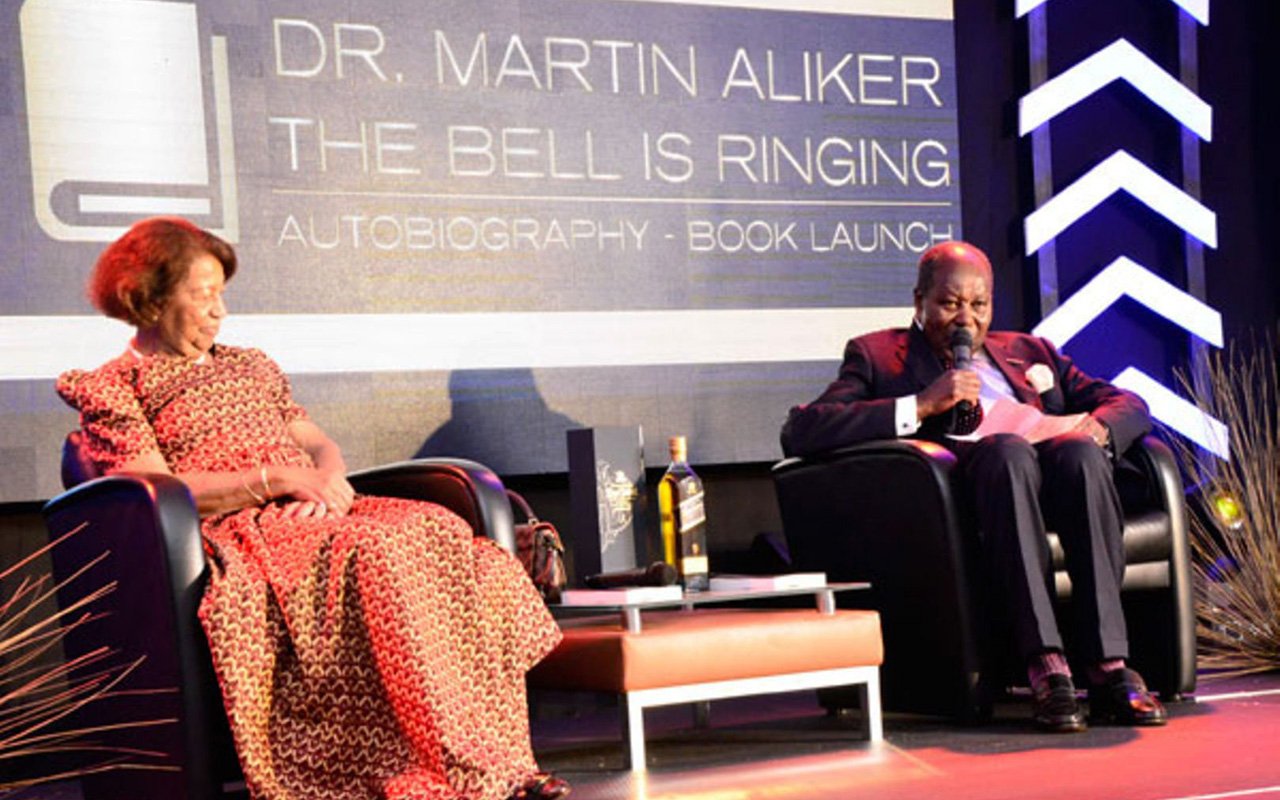

In his biography The Bell is Ringing (with David Gibbs and Hugh Macmillan) Aliker singles out the modern attributes of Lokech, a lifelong diarist who reinvented himself many times in different administrative roles.

Lokech, he said, was multi-lingual and had a love of reading, keeping a subscription to The Times of London.

His father, the family’s station in the community and the long shadow of his older brother Daudi Ochieng, later an MP and confidante of Kabaka Mutesa II, would imprint an ambition for rooftop of society, a brave confrontation of the complex world and a work ethic measured to match the reward for the good things of life.

Dr Martin Aliker and his wife Camille

At home and by the side of his beloved wife Camille, he was a modern family man, devoted partner who would put the birthday of a grandchild above a business meeting.

A leading man outside his door, he tended to follow his wife’s advice and increasingly relied on her relationships with his wider circle to navigate the evening of life.

An image conscious aficionado of the confident man, the man of substance he sometimes came across as valuing the materiality of success other than emotional attributes such as identity, culture, and ideology.

In an interview with the Institute of Commonwealth Studies (University of London) a decade ago, he was openly disdainful of the political class who he equated to rewarding themselves with middle class perks without deserving it.

Politics was for “those who were failures in life: people who had no definite careers or good prospects for the future,” he said of the political elite.

They were the guys who “had no degrees” like Uganda’s independence leader Milton Obote, a rival of his brother Daudi Ochieng and the Kabaka who Obote overthrew in 1966 in one of the dramatic and bloody episodes in Uganda that watermarked two and a half decades of conflict and civil war.

Dr Martin Aliker

Unlike his autobiography in The Bell is Ringing which is sometimes light on detail, the interview with Dr Sue Onslow revealed Aliker’s complex relationship as an interpreter of the interests of international capital and its political sponsors in the West and their interaction with rebels, liberators, and professional politicians in the changing Africa, especially during the fall of Apartheid in South Africa and the end of the Cold War.

All through these episodes he retained class libertarian views to the extent that a good education, an open mind, and a commitment to wealth creation allowed him to move seamlessly between African leaders on the one hand, global political players on the other and often as a messenger for either side while being domiciled in companies in which he had a leading role.

In both worlds

He was on the scene as chairman of the board of Lonhro, a British mining and agriculture company whose CEO Tiny Rowland played a role in the early years of the NRM after 1986.

Rowland and the Lonhro company were seen as synonymous with British political and commercial interests and Aliker had a foot in both worlds, being able to interact with close personal friends in Britain and engage with Ugandan politicians, including fairly new players such as President Museveni at the time.

Having been active for a longer period, Aliker appeared comfortable in the role of facilitator and ruled himself out of higher office.

Following the fall of Amin, he says, Gen Tito Okello Lutwa (later a coup leader who overthrew Milton Obote for a second time in the latter’s career) was “the head of the Ugandan fighters – alongside the Tanzanians – against Amin”.

Aliker says Lutwa “came to Moshi (Tanzania) and called me and said to me, “When we reach home, we – the fighters – want you to be the president of Uganda.”

“I knew that if it was announced on the radio in Uganda that I was going to be the president, by the time I got there my parents would be dead,” he said, adding “So, I persuaded Tito Okello to allow [Yusuf] Lule to become the president, and it took me two days trying to convince Lule to become the president because he was not sure whether my tribesmen – the Acholi, who were fighting – would accept him. So, I am the one who made Lule the president. Otherwise, if I had been ambitious enough, I would have taken over”.

Thus, perhaps, a president Martin Aliker did not make an appearance in the turbulent history that followed the military government of Idi Amin.

But the reference to a lack of ambition was perhaps false modesty. Aliker’s vision of order and progress was tied to an earlier time and he while he abided with the tumultuous period of African nationalism he was ambivalent about self-rule as manifesting a better quality of life or the protection of property and liberties fundamental for the self-made man to thrive and prosper.

“I have to make a confession. I was one of those people who did not see the need for independence in Uganda, because life was very comfortable under the British. We didn’t really see what more we wanted. We had everything: there was never any segregation in Uganda, the salary scales were the same, the facilities were all available. So, the agitation for independence was only among a few people,” he tells Onslow, suggesting a gulf between him and the sentiments elsewhere about the exploitative nature of British colonialism or the tensions between the colonial administration and African labour, especially in the agriculture sector.

If he was uncomfortable with African political power, he aided it with contacts abroad while separating himself from some of its more notorious attributes, such a public sector corruption and ideological parochialism.

Ms Margaret Thatcher

On encountering former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher as an emissary of the short-lived presidency of Godfrey Binaisa, the scene was almost strictly business.

“Binaisa, as president, said, ‘Look, you know the people in England. Please go and ask for help,’” Aliker recounts.

In England, he goes to meet with Edward Du Cann (a conservative British MP who was chair of the 1922 Committee that was instrumental in making Thatcher the first woman to head the party and serve as British prime minister). Du Cann was also on the board of Lonhro.

The meeting took place in his home. After preparing a written list of demands, Aliker was invited to dinner.

“When I got there, there was the prime minister of the United Kingdom,” Aliker said.

This for an African businessman, even though an emissary of Binaisa, could have been overwhelming for some.

“Thatcher was having a sherry and I was given a sherry and she had my paper… [and] she said, ‘This I can do, this I can do, this I have to ask my colleagues, this will take time, this I can do.’ And, in five minutes, she had taken a decision,” he said, a business-like quality that he no doubt appreciated.

Aliker brought these qualities, directness, quick decision making and focus to his later career as “chairman of chairmen”.

Former Monitor Publications board chair Aliker (right) with editors Charles Onyango-Obbo (left) and Wafula Oguttu (second right).

In two instances when Monitor Publications, where he was board chair, clashed with the government, including after controversial death of Dr John Garang (a friend of his), he was able to convey the values of the publication as a business to President Museveni for whom he performed similar tasks for Lule and Binaisa.

It helped that he was friends with the Aga Khan who was the owner of Nation Media Group that had acquired a majority stake in the Monitor.

While he admitted that he did not “enjoy Cabinet” when he served in formal roles in the government, he relished informal backroom engagement if it produced results.

A close personal friend said Aliker in one of the last conversations she had with him said “do it now” after she mentioned only for a second time her desire to go back to school.

“Do it now,” he repeated.

Aliker in a lifetime of happy effort built a network of contacts unrivalled by what is on the record for a Ugandan entrepreneur who doubled as an advisor to the powerful.

He was in Libya when Nato started bombing the country. After a perilous journey, he met with Bashir Saleh Bashir amid a hail of bombs.

The message he had from President Museveni to the Libyan leader was, however, not delivered directly because Gaddafi was afraid his movements were being tracked.

“Looking back, I am fairly certain that Gaddafi was in the bunker where I met Bashir,” he says in his book.

Of his many adventures, the episode depicts his character. Before departing for Libya, he asked his wife for permission.

She did not object, he says, otherwise he would have “disobeyed the President”.

The affair with Gaddafi started a while before the crisis that led to his death and the collapse of Libya. It is worth recounting in Aliker’s own words here.

“As far as Lockerbie was concerned, Gaddafi was desperate to get his two arrested countrymen freed. So, he lobbied many governments, including the Israeli government. And he went to Museveni as chairman of the OAU and asked him if he could talk to the Americans. Museveni had no connection with the Americans, so he called me and he asked me to go and plead with the Americans to allow the case to be transferred to the UK. I remember telling him, ‘Sir, I have succeeded in doing many things for you, but this one is going to be difficult because American public opinion is very much against the Libyans.’ And he said, ‘Oh, well, you just go and add your little voice.’”

Former US president George Bush

After he was successful in the transfer of the case of the two Lockerbie suspects to the UK, Aliker accompanied Museveni to America and sat in on a meeting with president George Bush and National Security Council advisor Condoleezza Rice.

“George Bush introduced Condoleezza Rice as the adviser, and Museveni introduced me to George Bush as his adviser. So, George Bush said, shaking my hand, ‘Ah, you and Condie will work together very well.’ So, when the meeting ended, Ms Rice said to me, ‘We’d like to see you in Washington, when can you come?’ I said, ‘Anytime.’ She said, ‘Tomorrow?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ So, the next day, I went to the White House and we sat down with Condoleezza Rice and she started telling me, ‘The president told your president the following: Tell Gaddafi to denounce terrorism; tell Gaddafi to denounce weapons of mass destruction; tell Gaddafi to accept responsibility for Lockerbie, and to pay compensation.”

“And while we were talking, the president walks in: ‘How are you guys getting along?’ And Condoleeza Rice said, ‘I’m telling Martin what we discussed.’”

Contact with Gaddafi would continue but the affair ended after the start of the Arab Spring and mostly because, according to Aliker, Gaddafi did not accept responsibility for Lockerbie.

Thus did Aliker take part in arguably one of the most spectacular collapses in recent African history that remains an inflection point for many Africans.

Aliker will be buried at his ancestral home in Aworanga, Gulu, today.

“Do it now” is a fitting epitaph for the self-declared chairman of chairmen.

He who valued the weight of a man’s reputation and the esteem with which he is regarded in his community is the only true tribute worthy of everyday effort and exertion.

In shorthand, he may leave a diary note to today’s Ugandans and Africans a message to believe that hard work and diligence, a vigilant protection of one’s reputation, especially by following the professional rules of one’s trade that can lead to not only financial reward, but the long-lasting gratitude and acknowledgement of one’s peers and community. These values writ large would also do credit to the nation.

Conversely, in the age of the individual, not as a reflection of society, like in the old days but as a digital mirror of himself, the absence of the pressure to heed values such as merit and trust may leave the doctor, family man and man about the world with some regret about the state of the world today.

But he would probably say get on with it and “do it now” if you have ideas on how to right this world.