Prime

Eight questions that court dealt with in Gen Sejusa’s fight to quit UPDF

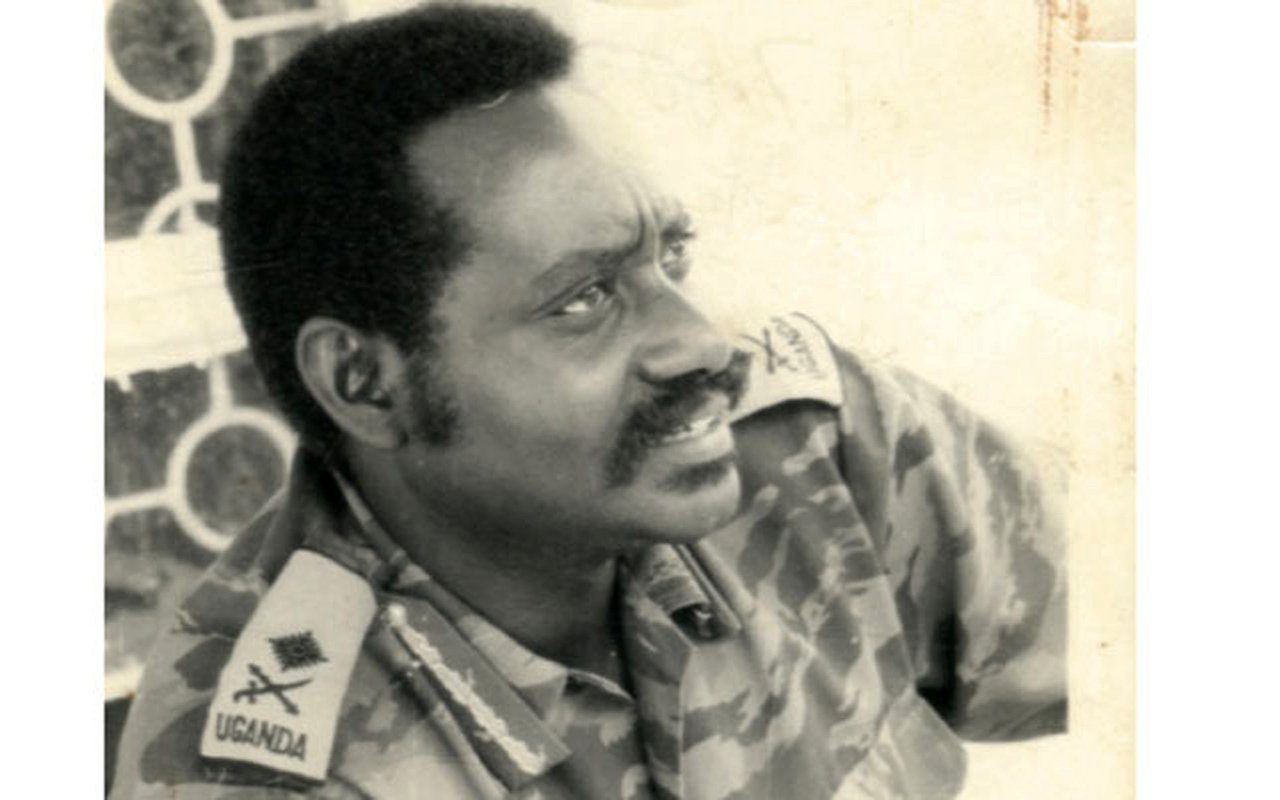

Gen David Tinyefuza (now Sejusa) tried to resign from the army in 1996. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- The issues were contained in the judgement delivered by Justice Seth Manyindo, one of the five justices who heard the case including:

- Whether on his appointment to the post of presidential advisor on military affairs the petitioner became a public servant by virtue of the terms as spelt out in the letter of his appointment.

Twenty seven years ago last week, on April 25, 1997, the Constitutional Court while delivering its judgment in Constitutional Petition Number 1 of 1996, ruled that the Army High Command did not have the constitutional power to challenge and reverse Maj Gen David Tinyefuza’s resignation from the Uganda People’s Defence Forces.

Gen Tinyefuza, now Sejusa (RO 00031) had on December 3, 1996, written to the army notifying it of his decision to resign, citing, among others, remarks that he had made before a committee of Parliament which was probing the army’s execution of the war against the Joseph Kony-led Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).

The minister of State for Defence then, Mr John Patrick Amama Mbabazi, wrote back in a December 8, 1996, letter saying the Commander-in-Chief had advised that he channels his resignation through the Army Commissions Board.

Gen Tinyefuza then filed a suit in the Constitutional Court. Prior to the hearing of the case, his legal team and that of the Attorney General agreed that it was the wrong platform. He advised him to seek his resignation through the Army Commissions Board.

The soldier then filed a suit in the Constitutional Court. Prior to the commencement of hearing of the case, his legal team and that of the Attorney General framed 11 issues for the court to focus on. The issues were contained in the judgement delivered by Justice Seth Manyindo, one of the five justices who heard the case. These are listed here below:

1. Whether on his appointment to the post of presidential advisor on military affairs the petitioner became a public servant by virtue of the terms as spelt out in the letter of his appointment.

2. Whether upon his appointment with effect from February 2, 1994, the terms of service spelt out in the letter of appointment were the terms governing the petitioner and his service relationship with the Republic of Uganda.

3. Whether upon being offered new terms of service set out in the letter of appointment, the petitioner continued to be governed by the terms of his old employment too, in the Uganda armed forces.

4. Whether having served in the army and been appointed to a new position outside the military establishment, the petitioner continued to be a member of a regular Force as defined in the National Resistance Army Statute and the regulations made thereunder.

5. Whether in his new status, arising from his new terms of service set out in his letter of appointment the petitioner continued to be subject to military law, to which members of the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces (UPDF) are subject.

6. Whether to be a member of the High Command as defined or necessity also have to be a member of a regular force.

7. Whether the letter from the minister of State for Defence, which declared the petitioner’ resignation and departure from the army and the High Command “null and void”, was in effect a denial of the petitioner’s liberty and calculated to require the petitioner to perform forced labour.

8. Whether the petitioner resigned from the High Command and refused to be a member of a regular Force as a conscientious objector in accordance with Article 25(2) and 25(3) on the Constitution of 1995.

9. Whether the testimony given by the petitioner before the parliamentary sessional Committee on Defence and Internal Affairs was made on a privileged occasion and entitled the petitioner to immunity from any actual or threatened prosecution, harassment or victimisation guaranteed by Articles 97 and 173 of the Constitution of 1995, and the provisions of the National Assembly (powers and privileges) Act Cap. 249 Laws of Uganda, 1964 Edition.

10. Whether the letter from the minister of State for Defence and the reported conduct of the other authorities in the government and the army amounted to a threat to the petitioner’s fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed and protected under Articles 20, 23, 25(2), 25(3)(c) and 97 thus justifying the Petition.

11. Whether the petitioner is entitled to the declarations and remedies prayed or any other.”

According to Justice Manyindo from those 11, arose eight “real questions for determination”. Those were:

1. Whether the testimony given to the Parliamentary Sessional Committee on Defence and Internal Affairs by the petitioner is covered by the parliamentary immunities and privileges provided in Article 97 of the Constitution.

2. Whether the letter of the minister of State for Defence (General) to the petitioner, declaring the latter’s purported resignation from the UPDF and its High Command null and void and the reported conduct of some government and army officers amounted to a denial of his liberty and a threat to his fundamental rights and freedoms and was calculated to require him to perform forced labour.

3. Whether having been appointed presidential advisor on military affairs outside the military establishment, the petitioner continued to be a member of the army.

A. If the answer to (3) is in the affirmative, whether the petitioner continued to be governed by the terms of his employment in the army and was subject to military law while also being governed by his terms of service as presidential advisor on military affairs.

5. Whether a member of the High Command must necessarily be a member of the army.

6. Whether the petitioner is a conscientious objector within the meaning of Article 25(2) and (3) of the Constitution.

7. Whether the petitioner has resigned from the High Command of the army.

8. Whether the petitioner is entitled to the declarations he seeks.

Ruling

Below are is the submission that Justice Manyindo made after listing the “real questions”:

“I should first and briefly address my mind to the principles that govern the interpretation of the Constitution. I think it is now well established that the principles which govern the construction of statutes also apply to the construction of constitutional provisions,” he said.

“And so the widest construction possible in its context should be given according to the ordinary meaning of the words used, and each general word should be held to extend to all ancillary and subsidiary matters.”

He added that in certain contexts a liberal interpretation of Constitutional provisions may be called for.

“In my opinion constitutional provisions should be given liberal construction, unfettered with technicalities because while the language of the Constitution does not change, the changing circumstances of a progressive society for which it was designed may give rise to new and fuller import to its meaning,” he said.

He added: “A constitutional provision containing a fundamental right is a permanent provision intended to cater for all time to come and, therefore, while interpreting such a provision, the approach of the court should be dynamic, progressive and liberal or flexible, keeping in view ideals of the people, socio-economic and politico –cultural values so as to extend the benefit of the same to the maximum possible,” he ruled. The role of the court, he said, should be to expand the scope of such a provision and not to extenuate it.

Therefore, the provisions in the Constitution touching on fundamental rights ought to be construed broadly and liberally in favour of those on whom the rights have been conferred by the Constitution, he added.

If a petitioner, he said, is entitled to the relief in exercise of constitutional jurisdiction as a matter of course if such a petitioner succeeds in establishing breach of a fundamental right, but hasted to add that the court may decline to grant such reliefs if they would perpetuate injustice or where the court felt that it would not be just and proper.

“The second principle is that the entire Constitution has to be read as an integrated whole, and no one particular provision destroying the other but each sustaining the other. This is the rule of harmony, rule of completeness and exhaustiveness and the rule of paramountcy of the written Constitution,” he said.

The third principle, he said, was that the words of the written Constitution prevail over all unwritten conventions, precedents and practices, adding that the court should not be swayed by considerations of policy and propriety while interpreting provisions of the constitution.