Prime

How courts have looked the other way when army officers do politics

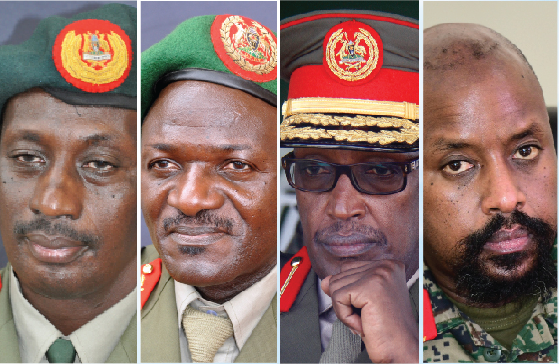

Gen Aronda Nyakairima, Gen Katumba Wamala, Gen Henry Tumukunde and Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba. PHOTO/COMBO

What you need to know:

- Conundrum. Those against rallies of serving military officer Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba have been advised to take the issue to the Constitutional Court for interpretation.

- But the court has previously ignored such petitions.

In trying to get used to crowds, President Museveni’s son, Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba, has made it a habit to address rallies from time to time, with the latest being the one he held in the eastern city of Soroti.

In his speech, Gen Muhoozi advised against land fragmentation and encouraged citizens to work.

“Whenever we meet them we encourage all our farmers and land owners to avoid the practice of land fragmentation,” Muhoozi said. “The youth it can’t be only dancing. No, you should also have some good ideas for the country.”

Bobi Wine tour: A chance for Opposition to resurrect

As usual, Muhoozi’s rallies raised a political storm with many wondering why a serving army officer would organise rallies contrary to the law, but Muhoozi’s minions, led by veteran journalist Andrew Mwenda, told them off, saying if anyone felt distressed they should take the issue to the Constitutional Court.

“I have consulted with the Attorney General of Uganda and lawyers in private practice, and they have told me there’s no law Muhoozi is breaking. If you believe there’s a law he is breaking, go to the Constitutional Court,” Mwenda says.

Maverick lawyer Hassan Male Mabirizi promptly filed a criminal case at Kumi Magistrates Court. In his criminal case, Mabirizi has listed Muhoozi, Speaker of Parliament Anita Among and her deputy Thomas Tayebwa, Health minister Jane Ruth Aceng, State minister for Education and Sports Peter Ogwang, inter-alia.

Mabirizi contends that Muhoozi and his group under MK Movement/MK Army, organised, managed, and addressed a political gathering where political statements and activities were made and performed.

Mabirizi accuses the group of managing an unlawful gathering contrary to Sections 56 and 57 of the Penal Code Act, conspiracy to commit a felony contrary to Sections 180 of the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF) Act, 2005, and Section 390 of the Penal Code Act.

Additionally, he says, Section 16 of the Political Organisations Act restricts members of the armed forces, public officers, religious and cultural leaders, and government-owned company employees from participating in partisan politics.

Professionalising UPDF

Within the context of professionalising the UPDF, in 2005, the UPDF Bill, which upon being assented to by the President became an Act, was tabled by Simon Mayende, then chairperson of the sessional committee on Defence and Internal Affairs.

Under Article 208 of the 1995 Constitution, the UPDF is cast as nonpartisan, national in character, patriotic, professional, disciplined, productive, and subordinate to civilian authority.

Still, there are a number of legislations in Uganda that stop active servicemen from participating in politics.

For instance, Section 15 of the Political Party and Organisations Act stipulates that a member of the UPDF, the Uganda Police Force, the Uganda Prisons Service or a public officer or a traditional or cultural leader, or a person employed in a company wholly owned by the government shall not— be a founder, promoter or another member of a political party or organisation; hold office in a political party or organisation; speak in public or publish anything involving matters of a political party or organisation controversy; or engage in canvassing in support of a political party or organisation or of a candidate standing for public election sponsored by a political party or organisation.

Any person who contravenes sub-section (1) commits an offense and is liable on conviction, the Act says, to a fine not exceeding 24 currency points or imprisonment not exceeding one year, or both.

Its pursuit of transforming into a professional army, Anna Ruess in her thesis titled Politicisation, Professionalisation, and Personalisation of the Uganda People’s Defence Forces: The Military and the Pursuit of Stability in an Aging post-revolutionary Regime says conventional capabilities notwithstanding, the UPDF has not shed its revolutionary character.

“In the face of sharp criticism from the Opposition and civil society, the NRM regime tightly clings on to institutions of systematic politicisation of the army rooted in the revolutionary war and inscribed in the legal and institutional framework of the UPDF; army representatives in Parliament, political education for soldiers and ‘patriotic training’ of citizens by the army, and the productive role of the UPDF,” Ruess says.

The NRA/UPDF’s stake in political affairs, Ruess explains, was legitimised not only by its historical achievement but by the non-partisan principle.

In the NRM view, partisanship is associated with sectarianism and opportunism, but the UPDF’s political nature claims intrinsic sources that predate and supersede opportunistic involvement in politics, Ruess says.

Although Gen Muhoozi’s cronies are advising their adversaries to take the issue of his involvement in politics to the Constitutional Court, several Ugandans have previously taken that route, and the court has never determined the issue.

In 2013, President Museveni appointed then Chief of Defence of Forces (CDF), Gen Aronda Nyakairima, who has since passed on, as minister of Internal Affairs.

Private lawyer Eron Kiiza dashed to the Constitutional Court challenging Aronda’s appointment, saying it was unconstitutional since Aronda hadn’t retired from the army before taking up the position in Cabinet.

Kiiza contended that Aronda’s appointment offends Article 2 of the Constitution, which makes the Constitution Uganda’s supreme law.

Kizza said Aronda’s ministerial appointment breached Sections 37 and 99 of the UPDF Act.

These sections bar soldiers from civil employment. By extension, Kiiza argued, an officer would have to retire from the army before taking up civil employment.

Kiiza insisted that the office of the minister is a political office, hence Aronda’s appointment contravenes Section 16 of the Political Parties and Organisations Act, 2005, which prohibits soldiers from participating in partisan politics.

According to Kiiza, by Museveni appointing Aronda to the said ministerial position, he offended Articles 99 (1), 2, and 3 of the Constitution which enjoin him as the President to respect, abide, uphold, and safeguard the Constitution and other laws.

He argued that Aronda’s appointment contravened Article 208(2) which stipulates that every member of the UPDF must be non-partisan and subordinate to civilian authority.

Accordingly, he insisted that the Cabinet Aronda joined as a minister is a partisan institution since Uganda is under a multiparty dispensation.

“Uganda is currently ruled by the NRM government and all members of the Cabinet are partisan owing to Article 117 and common law doctrine of collective responsibility. It is not constitutionally or practically possible for a person who is part of the Cabinet to be non-partisan,” Kiiza’s notes read.

MUST READ: Why the gun may not serve Muhoozi

Equally, he maintained that under Article 208 (2), civilian authority includes Cabinet, hence Aronda, a military person, could not be part of civilian authority.

“One cannot be part of civilian authority and at the same time be subordinate to it. For a senior army officer to join Cabinet, the effect is for the military to be fused with civilian authority to which it is supposed to be subordinate. Can a person be subordinate to himself?” Kiiza argued in his petition.

The Attorney General defended Aronda’s appointment, saying it was in conformity with Article 113 of the Constitution.

The article stipulates that, “Cabinet ministers shall be appointed by the President with the approval of Parliament or persons qualified to be elected Members of Parliament.”

That article, the Attorney General said, does not preclude a serving army officer, adding that Aronda did not become a politician by joining Cabinet, as one can serve the government without doing politics.

By the time Aronda died in Dubai, while in transit from South Korea on official duty, the petition had not been heard and to date, the Constitutional Court has never ruled on the matter that would have gone a long way in settling the debate of military’s involvement in Uganda’s politics, living Kiiza livid.

“The court always came up with a reason not to hear my petition until Aronda passed on and they said hearing it doesn’t make case,” he says.

Enter Gen Katumba

Aronda’s appointment seemed to have stimulated Museveni, who also appointed Gen Edward Katumba Wamala as minister for Works and Transport in 2017, without requesting him to retire from the army.

Robert Mugisha and Deusdedit Bwengye challenged Gen Katumba’s appointment in a petition filed at the Constitutional Court on May 29, 2017, saying the appointment was illegal because he had never resigned or retired from the UPDF.

The two contended that Katumba’s appointment as Minister of State for Works ran counter to UPDF’s cardinal rule of being nonpartisan and subordinate to civilian authority under Article 208(2) of the Constitution and Section 99 of the UPDF Act.

The duo said Katumba’s appointment by the President and his subsequent approval by Parliament on February 14, 2017, subjected him to a conflict of interest, which could compromise his office as a minister.

When Katumba was sworn in as a serving army officer, the duo said in their petition, he took an oath of allegiance, which included; first to the President and second to the Republic of Uganda, and to defend the President and second the Constitution against all enemies under Section 52 and fifth schedule of the UPDF Act, 2005.

Yet when Katumba was sworn in as a minister, they said, he swore to bear true allegiance only to the Republic of Uganda, not to the President, and to at all times truly serve first the Republic of Uganda and second freely give counsel to the President, which they say is inconsistent with Articles 133 (4), 114 (5) and 208 (2) of the Constitution.

“That Section 38(2) of the UPDF Act 2005 as far as it permits officers and militants of defence forces to be attached or seconded as political or administrative heads of ministries, is inconsistent with and in contravention of Articles 205 (2), 208 (2) and 257 (1) (S) of the 1995 Constitution of the Republic of Uganda,” the petition, which was never heard by court, said.

Although he is now retired and in 2021 stood for presidency, Gen Henry Tumukunde was appointed minister of Security in 2016, years before he could retire.

Entrenched military presence

One issue that the Constitutional Court resolved but yet again entrenched military presence in civil institutions is the presence of 10 army representatives in Parliament.

Activists had always argued that Parliament is a partisan institution and thus the army which, at least in theory, is non-partisan, should stay out of it. But in 2019, the Constitutional Court okayed the presence of the military in Parliament.

Ellady Muyambi, a private citizen who filed the petition, insisted that the army can’t be in Parliament since Uganda has moved away from the single-party system which was termed the Movement system to the multiparty dispensation, but the five justices had different ideas.

“From the foregoing, it’s clear that the Constituent Assembly was alive to the contentions raised by the petitioner. However, it recommended that it was important to have army representation in Parliament. The majority were of the view that having the army represented in Parliament would aid in the execution of its duties and functions,” Justice Fredrick Martin Egonda-Ntende, who wrote the lead judgment, explained.

“It is also clear that the Constituent Assembly intended for the army to be represented in Parliament during both systems of government [Movement and multiparty]. It was never intended by the framers of the Constitution for the army representation in Parliament to be in abeyance during the multiparty system,” Justice Egonda-Ntende wrote.

In theory, Uganda’s current Constitution recommends a patriotic and non-partisan UPDF, and mandatory political education, prescribed in the successive defence laws, is the primary tool to form a patriotic, non-partisan Force.

But according to Ruess, there is little political education troops go through after the nine months of induction training and political commissars have lost influence and prestige.

“Many soldiers have little illusion about the purpose of political education. They teach you how to support the regime. Moreover, most soldiers, including the officer corps, are preoccupied not with lofty revolutionary ideals but with sustaining the livelihoods of their families on a meagre army pay,” Ruess says.