Janani Luwum: Celebrated abroad, forgotten at home

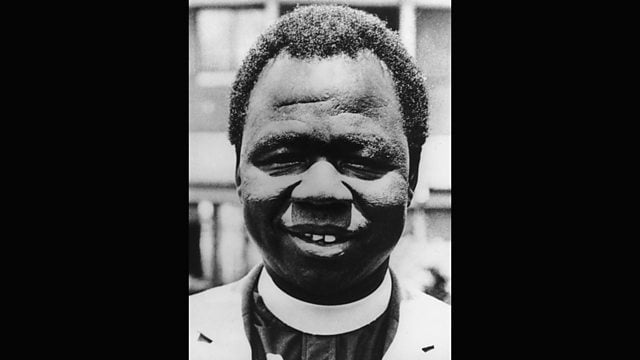

Former Archbishop of Church of Uganda Janani Luwum. Photo/FILE

What you need to know:

- On January 19, I had the opportunity to address the House of Bishops at the Lweza Conference Centre on the theme ‘Remembering St Janani Luwum in his homeland.’ Below is an abridge version of my speech.

Your Grace, my Lord the Chief Justice, my Lords the Bishops:

I thank you ever so much, Your Grace, for kindly inviting the Chief Justice and I to address this session of the House of Bishops. We are very grateful for this opportunity to share with you some perspectives on the all-important and long-overdue project: the development of a befitting memorial for our Archbishop-martyr, St Janani Luwum. We consider this a great honour and privilege. I might add that it is particularly congenial to be doing so in this well-appointed spot of Lweza.

Why this global remembrance?

I was very fortunate to have known the archbishop personally. I am among the children who grew up at his feet. To this day, I conserve many vivid and fond recollections of him.

I remember his passion for proclaiming the Gospel of Christ. His deep and unbending faith. His unflinching prophetic voice, for human rights and social justice. His quiet, steely courage and confidence. In the face of everything, he never wavered. He remained calmly confident and faithful – literally unto death.

In the midst of the show trial at Nile Mansions (February 16, 1977), he leaned over and whispered to his neighbour, “They are going to kill me.” And as the soldiers separated him from his fellow bishops and were now taking him to the fateful encounter with Idi Amin, he turned to his colleagues, smiled and calmly said, “I am not afraid. In all this, I see the hand of God.” This was his last public utterance.

Some of you who might have known him in life, will recall how the archbishop exuded such palpable love and joy. You will remember how he always had a glowing face, wrapped in this warm, loving smile. Like his much-beloved mother, Mama Aireni, he truly had the gift of love.

Of physical stature, the archbishop had an imposing charismatic presence. Yet he had an easy disposition of such simplicity, gentleness and warmth about him. That is why all stations of persons readily felt at-home in his presence.

The archbishop set an example of simple, uncomplicated integrity in all things. He was oblivious to the allure of materialism. He led a modest, giving, unpretentious life.

As a person and as a leader, he was a great unifier and reconciler of people -- larib-dano. That is why, as archbishop, he became a major uniting and healing force within a fractured Church (this Church) and a country in terrible agony.

I remember him often coming back with still-slides from various conferences, held in places with exotic names, place-names that our malakwang tongues could not roll around – Uppsala, Lausanne, Geneva, Utrecht. Much later, I would learn that these were some of the venues for international ecumenical gatherings.

Within Uganda he pursued the same ecumenical ethos with conviction. In Gulu, for example, he and bishop Cypriano Kihangire (then Catholic bishop of Gulu) became great friends and collaborators. In Kampala, he forged a warm relationship with Cardinal Emmanuel Nsubuga (then Catholic Archbishop of Kampala).

We remember Archbishop Janani being especially devoted to young people. He was a hunter for talent, with a keen eye particularly for young talent. He attracted and mentored a lot of young people. As we know, these included Archbishop emeritus, Henry Luke Orombi, and former Archbishop of York John Sentamu. He was also a great advocate for providing systematic quality education for the clergy, with opportunities for their continuous formation.

Well ahead of his times in the Church, he pursued a clear development agenda; he particularly promoted rural development, women empowerment and food security. One of the fruit of his vision and innovation is the now-completed Church House project. He obtained the land, initiated the project and promoted it vigorously. He often spoke about this project – it was very dear to him.

Ironically, there is one aspect of the profound impact of Archbishop Janani’s martyrdom that is little known or appreciated in Uganda. It was the searing martyrdom of the archbishop that marked the pivotal turning point, for the fate of the Amin regime and the subsequent liberation of Uganda.

Not since the killing of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury (March, 1556) and Archbishop William Laud, also of Canterbury (January, 1645), had an Anglican primate been eliminated in this way. An unthinkable line had been crossed by Amin. At the international level, the impact was huge. This dark deed became the game-changer. Finally, a sober realisation dawned on a hitherto jaded and complacent international community, particularly the Western world, that the Amin regime simply had to go. This marked the beginning of the end for Idi Amin.

The martyrdom of the archbishop is really what set the stage and created the mood that greatly facilitated and buttressed the subsequent, and ultimately successful, Tanzania-led campaign to remove the Amin regime. Absent this, the international community would have almost certainly vetoed Tanzania’s military involvement, with the hallowed refrain: “No interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign state.”

So, in Archbishop Janani, we have a great hero of faith. We have a compelling global role model. We have a moral icon. And we have a national hero of seminal consequence. This then is the man for whom we propose to develop a befitting living memorial in his homeland, Uganda.

When I look around us today, I am struck by how much the values and moral rootedness exemplified by Archbishop Janani could not be more pertinent and powerful for contemporary global society – I mean for the world, for Africa, for Uganda, for the Church. Speaking of our own society particularly, we are in the throes of a deep and radical moral collapse. We are witnessing a moral free-fall. We have wilfully settled for and conferred normalcy on a shauri yako moral space, a space in which anything goes.

In St Janani, we have a compelling role model for the world – an authentic hero, whose life and example can inspire and challenge all of us, across national, racial, political and faith identity boundaries.

Components of the memorial

What then, specifically, does the proposed memorial encompass? Chiefly, the memorial entails undertaking three closely related component tasks.

The first component task is the physical transformation of Wii Gweng into a befitting and dignified memorial and pilgrimage site. This capital development project is the most important and pressing task facing us today.

The second component task is organising and animating the annual prayer and commemoration at Wii Gweng on February 16, as the central national and international commemoration. We are grateful that government has decreed this day as a national public holiday in Uganda.

The third component task is to develop a portfolio of selected programmes, information and documentation, for the purpose of generating awareness and knowledge, reflection and emulation, on the life and example of Archbishop Janani.

Various activities can be developed under this rubric. For example, an annual foot pilgrimage was inaugurated in 2020. The foot pilgrims set off from the Archbishop’s Palace at Namirembe, and concluded their journey at the martyr’s graveside at Wii Gweng.

When then Archbishop Stanley Ntagali (together with then prime minister Ruhakana Rugunda) launched the pilgrimage programme, he warmly invited all Christians from different denominations, to participate in the pilgrimage. The pilgrimage that year marked a historic watershed: a united contingent of Anglican and Catholic faithful, trekked together in fellowship, singing and praying together, for some 550kms, from Namirembe to Wii Gweng.

Celebrated abroad, forgotten at home

Around the world, there is great devotion and celebration of the martyrdom and ministry of St Janani. Churches, chapels and schools have been named after him.

Consider this. Within weeks of his martyrdom, on March 30, 1977, a special memorial service was held for Archbishop Janani at Westminster Abbey in London. This was followed, in 1998, by the unveiling of his permanent statue (together with nine other Christian martyrs of the modern era, drawn from different denominations) at the western entrance of Westminster Abbey; the Queen and Prince Philip attended this ceremony.

In a similar way, the martyrdom of Archbishop Janani occasioned the dedication of a special chapel – the 20th Century Martyrs Chapel – at Canterbury Cathedral in 1978. And in the Church of England’s calendar, celebrating saints and martyrs, February 17 is observed as the Feast of Janani Luwum.

We, in the land of his birth, are only now ‘playing catch-up’ to the devotion and celebration in the rest of the world. It is astonishing that some 45 years after the martyrdom of Janani, there is hardly anything to show in his homeland, nor in the ecclesiastical province of his stewardship. Speaking very personally, as a Christian and a Ugandan, I feel great shame about this situation.

We must come together, as Christians and as Ugandans, to exorcise this national shame and redeem this situation.

Mr Otunnu is co-chair of the national organising committee of St Janani Luwum Memorial. He is also the author of St Janani Luwum: The Life and Witness of a 20th Century Martyr.