Leprosy and the creation of leper’s colonies in Uganda

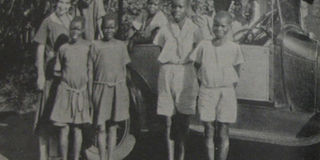

Symptom-free children leaving Kumi Children’s Leper Home and returning to their parents in August 1934. Photos | leprosyhistory.org

What you need to know:

- In Uganda, there were leprosy camps which were reported to contain 551 cases between the 1820s and 1850s. There were Leprosy Camps in Busiro, Teso, Buddo and Bunyoro. Henry Lubega writes how the pandemic created territories.

Christianity in Uganda was the forbearer of colonialism in Uganda as was the case in many colonised African territories.

As a result, religion had a strong influence on colonial administration policies. One such area was health. Between 1927 and 1934, Christian missionary societies opened four leprosy settlements in Uganda later called leper’s colonies.

The missionaries running the settlements doubled as medical officers in the colonial government, which funded the settlements. Though it funded the settlements, colonial officials viewed medical missionaries with suspicion. This was so because the government and the missionaries had a different view of the Africans.

To the colonial administrators, a healthy African is a source of labour, while to the missionaries a healthy African is a soul to be won for Christ. Despite their different view of an African,both the colonial government and the Anglican missionaries had a mutual interest in Uganda as a civilised Christian protectorate. It was the desire for a civilised protectorate that forced government cooperation in the treatment of leprosy.

The settlements

The first settlements or leper’s colonies as they were later called were a creation of the Church Missionary Society CMS, (Anglicans) and two factions of the Catholic Church the Mill Hill Mission (MHM) and the Franciscan Missionary Sisters for Africa (FMSA).

In 1927, Dr. C.A. Wiggins a CMS missionary and a former Principal Medical Officer of the Uganda Protectorate, opened a children’s out-patient leprosy centre in Kumi. Shortly after he opened an adult centre near Ongino. In 1930 the two centres became in-patient hospitals or settlements. Ten years later in 1940, the two settlements housed more than 1000 patients between them.

Another CMS-run settlement was in western Uganda started by doctors, Leonard Sharp and Algie Stanley Smith. It was opened in 1931 at Bwama Island in Lake Bunyonyi. Like its counterpart in eastern Uganda, the settlement on Bwama Island was run by one visiting doctor and two resident female nurse missionaries.

The District Medical Officer for Kigezi was against a leper’s settlement on the lake, citing the bad location of the settlement, lack of resources, and man power.

He went on to say “The leper camp must be made so attractive that patients will clamour for admission. The mode of living, the food, the climate, the amusements must all be far superior to that enjoyed by the natives in their natural habitat, and furthermore the curative or ameliorative results of treatment in the camp must be so startling as to attract the natives’ attention.”

In 1932, the Catholic missionaries opened two settlements. An FMSA nun and nurse, Mother Kevin founded Nyenga Catholic leprosy settlements in 1932 and in 1934 she founded another one in Buluba. The two were run by an FMSA Mother Superior and MHM chaplain respectively.

The government-owned Uganda Herald newspaper of July 21, 1933 stated the three main reasons why the Bwama Island settlement was created. “This leper colony was formed with three main ideas, and briefly these are to protect the general population from infected people and to cause migration, to relieve the suffering of the lepers themselves, and to cause the arrest of the disease among children by treatment so as they can live useful lives.”

In a letter to the CMS headquarters in Britain, Rosa May Langley, a CMS missionary, described the importance of the settlement to the missionaries. “I would like to add that first and foremost, the evangelists’ side has been…assured.

We are absolutely free as far as religious instruction is concerned and have seen real evidences of changed lives and definite conversions with the co-operation of the Holy Spirit…To us of C.M.S., all God’s children, the extension of His kingdom here on earth is the point that is above all others when considering if the work is worthwhile or not.”

The missionaries had special attachment to the treatment of leprosy drawing from Jesus’s examples when he healed a leper. “The poor victims have nothing to live for in this world, but under the care of the Sisters their great sufferings are relieved, their souls…comforted and strengthened by the rites of the Church,” wrote Mother Kevin in Worldwide Appeal for Lepers.

Kumi Leprosy Centre, Uganda

In treating the lepers, children were separated from their parents before they become disfigured by infections from their parents. Writing in the 1936 edition of the Medical Mission Auxiliary Year Review, Dr Wiggins wrote, “It is a wonderful work to cut off the entail of a bad past and to give children a real chance. The majority of those boys and girls will be discharged in a few years symptom free, their lives redeemed from suffering and misery, and the future for most of them is full of brightness and hope.” The children by the time they left the centres were good Christian converts.

Government’s role in fighting leprosy

Though settlements were started by missionaries, their survival hugely depended on the goodwill of the colonial administration. Grants totalling £3,998 annually funded the activities of the four settlements. According to the colonial administration’s 1939 health report, this accounted for one percent of the entire medical department budget. Besides operational grants the colonial government regularly provided specific building grants to the settlements for the construction of dormitories.

In 1948, a Uganda leprosy survey was carried out by the East African Inter-territorial Leprologist Dr James Ross Innes. The survey concluded that measures taken by authorities in Uganda to combat the disease were not sufficient. The survey indicated that out of the 100,000 leprosy cases in Uganda, 20,000 were highly infectious, of which only 3,000 were being admitted to the leprosy settlements.

The report not only faulted the location of the settlements, it also stated that “only 3.7 per cent of the people with leprosy in Uganda were receiving treatment, and that only eight medically-trained Europeans were actively engaged in leprosy work.”

The Innes report also highlighted the disparity in government funding of the settlements. Depending on the numbers each settlement had, government allocated 3 British Pounds to every in-patient at the Catholic settlements in Nyenga and Buluba while those at the CMS settlement on Bwama Islands were allocated 1.70 British pounds.

Church and government unite to fight leprosy

Besides their differences on how they viewed the local population, both government and church had some shared mission about the people of the colony. Their common mission was humanitarianism and the civilising mission.

To the religious pioneers of the leprosy hospitals the Christian appeal was the driving desire for their work. Dr Wiggins, the CMS missionary and founder of Kumi Hospital, was a retired Colonial Medical Officer, after which he became an ordained priest in England.

“It is the special privilege and joy of the medical work that it meets the need of the down and outs, most wretched and unfortunate of men, women and children,” wrote Dr Sharp, the founder of Bwama Island leprosy settlement on Lake Bunyonti. Writing in Worldwide Appeal for the Lepers, the founder of Nyenga and Buluba leprosy settlements, Mother Kevin said, “For the sake of humanity…we appeal to you to send a donation.” The colonial government saw the settlements as “a perfect venue for enacting the civilising mission,” wrote Beidelman in Colonial Evangelism.

The Bwama Island settlement became a model leprosy settlement. “It was a regular feature in the tours of Europeans around the area, from King Albert of Belgium, to an American film crew, to colonial staff who were advised to tour the leprosy settlement while visiting Lake Bunyonyi for holiday,” wrote Megan Vaughan in Curing Their Ills.

In an effort to draw leprosy patients to the settlements, the colonial government gave them incentives. These included things like exempting all those at the settlement from paying poll tax, providing transport for the patients for specific needs, dictating agricultural and housing policies for those who had proof that they were receiving treatment, among others.