Prime

Monitor at 30: A journey of endurance, innovation and bold news reporting

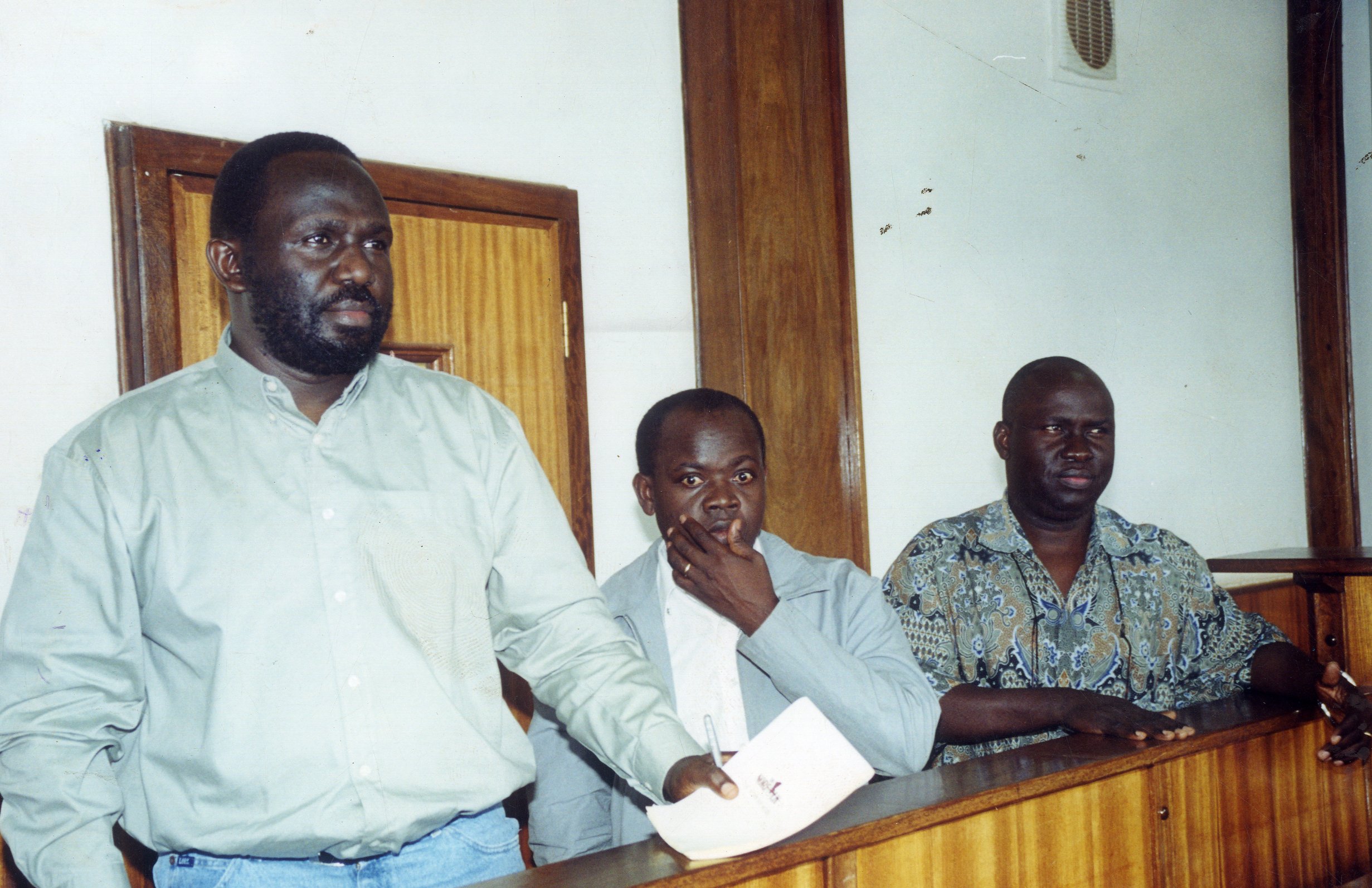

L-R: Former Monitor editor’s Charles Onyango-Obbo, David Ouma Balikowa and Wafula Oguttu in court. PHOTO/ FILE

What you need to know:

- The Monitor was born at the tail end of the honeymoon period for the NRM government and the beginning of a new phase of more questioning and scepticism.

Thirty years ago this month, in July 1992, a newspaper called The Monitor published its maiden issue.

The very first front page lead story in that edition was written by Susan Nsibirwa, a journalism student at Makerere University at the time.

The same Nsibirwa is, 30 years later, a member of the paper’s board of directors. This, alone, captures the passage of time and the sense of continuity.

The Monitor would go on to become a staple in Uganda’s news media and one of the most influential voices in Uganda’s post-independence history.

The Monitor was born at the tail end of the honeymoon period for the NRM government and the beginning of a new phase of more questioning and scepticism.

In 1992, there was still an assumption that the NRM government was a general coalition of the southern Bantu-speaking tribes, a civilised people who had restored sanity to Uganda.

Overall, the chaotic final six months of 1985 had been put behind and with a new national army composed of outspoken officers who by profession were medical doctors, lawyers, political scientists and economists, certainly this really seemed like a brand-new chapter in Ugandan history.

There was still, by and large, an assumption that the darkest chapters in Uganda’s post-independence history had been those between 1966 and 1986, especially 1971 to 1979.

This “peace ushered in” by NRM was, of course, a narrative dominant in the southern half of the country.

The same honeymoon period of 1986 to 1991 was, in Teso and most of northern Uganda, a time of much tribulation, displacement, and humiliation.

In 1992, political party activity was still banned by a legal notice from March 1986. President Museveni still blamed parties for Uganda’s post-independence instability.

Because The Monitor was founded by people with Nilotic- and Nilo-Hamitic-sounding surnames, an irritated NRM government felt the scrutiny it came under from the paper was because the paper’s founding editors were “northerners”.

Also, some of The Monitor’s origins in the Weekly Topic’s left-leaning nationalistic outlook shaped its reporting and tone in 1992.

In the early 1990s, the “Buganda question” was still being discussed as one of the important national issues.

The conservative Buganda establishment was often incensed at The Monitor’s irreverence toward Buganda institutions and traditions and made its displeasure clear.

Finally in 1993, its patience exhausted, the NRM government imposed an advertising ban on The Monitor by its ministries and departments.

The advertising ban was to last four years until 1997, although somehow the paper survived and even grew from a weekly to a tri-weekly and, in November 1996, went daily.

The privatisation of the economy that began in 1990 was in full speed in 1992, with a retrenchment underway of civil servants.

In Uganda, where most civil servants and corporate employees get by on allowances and per diem, the retrenchment of civil servants saw many slip into desperation.

The stress and trauma of this period soured the public attitude toward government.

Some of the paper’s best reporting was in 1994, in lead stories written by Dismas Nkunda and Steven Shalita, as well as Kevin Aliro, covering the three months from the shooting down of the Rwandese presidential jet and the fall of Kigali to the RPF guerrillas.

In 1994, The Monitor had to start competing for the attention of the more youthful demographic with the new, exciting medium of private FM broadcasting, although it also rode on the fierce competition between Radio Sanyu and Capital Radio.

As irony goes, starting in 2007 the same public that in 1992 felt The Monitor was a little too harsh on government now began to feel the paper had been compromised and might even be secretly on the payroll of the state.

Sunday Monitor cover of September 28, 1997.

Columnists in the mid to late 1990s gave the paper a distinct voice: Charles Onyango-Obbo’s Ear to the Ground serving as the paper’s flagship column, and there were columnists who used pseudonyms such as Melody, Jenny, Baba Pajero, and Pole Pole.

The playful atmosphere in the paper’s newsroom was brought in from the Weekly Topic, where the founders of The Monitor had been editors.

An attempt to publish a separate paper, Monitor Sport, was short-lived.

In 1996, there was an attempt to give more coverage to lifestyle and entertainment topics.

The paper went colour in 1996, and was the first to establish an online presence.

A July 1997 lead story by Andrew Mwenda in which Ugandans got to see the first photos in 12 years of the exiled former president Milton Obote in Lusaka, Zambia, not only completely sold out; even The Monitor’s own library file copy was lifted by one of the reporters and disappeared.

In March 2000, it was announced that The Monitor had been bought by Kenya’s Nation Media Group. The newspaper’s name was changed to Daily Monitor.

In 2005, Daily Monitor also ran a series presented by Andrew Mwenda based on notes taken during his interview of the former president Milton Obote in Lusaka.

Any series on Uganda’s political history, such as those about Obote, the Opposition leader Kizza Besigye, or NRA’s 1981-1986 guerrilla war, always and thought exception, gave Daily Monitor a lift of about 6,000 additional copies sold for the duration of the series.

Daily Monitor as the paper that questioned government’s policies and excesses has remained the constant image that most of the general public has of it.

It is remembered more for its front-page lead stories than for any other section or content.

The first accounts of safe houses operated by Uganda’s intelligence services, the secret purchase of TOW anti-tank missiles in 1992, the grenade attack in Wandegeya, Kampala, in which two Makerere University lecturers were killed, the mystery surrounding the plane crash carrying the army officer Lt Col Jet Mwebaze, the killing of Congolese at Kibimba by agents of the External Security Organisation in 1993 -- these and more were some of The Monitor’s riskier and bigger headline stories.

There were other news publications at the time, notably Hussein Njuki and Haruna Kanaabi’s The Shariat, that reported on the secret goings-on in the NRM state, most of which were far ahead of their time.

The Monitor had the advantage of being more mainstream and better distributed and marketed than The Shariat.

The controversy over a letter sent from London by the self-exiled Gen David Tinyefuza in 2013 led government to shut down the paper for 13 days.

In 2022, it continued with that publishing tradition, leading in June with the headline story on the army’s cryptic high-alert order while President Museveni was in Kigali to attend the Commonwealth summit.

All told, the pages of Daily Monitor, with its many shortcomings, is a rich repository of Ugandan political and social history over the last 30 years.

The paper’s back issues are endlessly quoted and referenced by students and authors working on their PhD and other scholarly dissertations.

One of the paper’s editorial failures during the 1990s was in not giving more news coverage and analysis on the Aids pandemic, at that time raging through Uganda and other sub-Saharan countries, and for which next to no Ugandan family did not lose an immediate or extended member.

Aids was the greatest existential threat to Africa since the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and yet The Monitor, like most Ugandan media, was preoccupied with the politics of power-sharing, the intrigue within the NRM state, and the public statements by various political and military figures.

As headline-grabbing as were many of these news stories, they now seem trivial and historically inconsequential with the perspective of 30 years, and yet the damage to society’s soul wrought by Aids or, for example, the civil war in Acholi, are still visible today.

Daily Monitor was founded at a time of scarcity of information.

Today, like all traditional media, it must navigate a new landscape in which the public is drowning in general information.

With information available at the click of a computer mouse or the tap of a smartphone screen, Daily Monitor, like other newspapers, will have to be guided more by digital data than by gut feeling, if it is to remain relevant to the public’s information needs.

A whole new purpose and format must be developed that reflects this new Internet and social media reality.

Depth of content and perspective rather than basic “what, when, where, and how” news will be required of it as it enters its 31st year.